Since time immemorial the Frankfurt kitchen, with its extreme rationalization of dimensions gathering in a minimal and thoroughly calculated space all necessary user, has been a symbolic object of the Modern movement in its many articulations, like Le Corbusier’s maison dom-ino or Bauhaus chairs. And, it must be said, in terms of critical and historiographical fortune the landscape of Modern is overwhelmingly crowded by male figures.

The recipient of this project, instead, “is a young, modem woman who doesn’t want to spend too much time on housework. She has other interests apart from cooking and looking after children”. And this project does not bear the signature of one of the many men just mentioned: it bears a woman’s one instead, the signature of Austria’s first female architect, Grete Lihotzky, who from her research would succeed not only in crystallizing a functional space capable of not making domestic life a totalizing yoke, but also in taking an influential role within a man-led debate.

Taking these two far-from-secondary details as the extremes of a new perspective from which to look at the Frankfurt kitchen represents a first step in a redefinition of historiography that is more attentive to roles unjustly kept in the shadows until recent times, such as those of women in the modern and Bauhaus.It also tells a story about another role, that of kitchen in the domestic ecosystem, in its purpose and its influence on our daily practices, which has not necessarily remained a priority in the following decades and in the present day: In June 1988, on issue 695, Domus decided to bring these issues to the fore, in an extensive essay of which we publish a historiographical excerpt, and the full text of which can be read in our Digital Archive.

The Frankfurt kitchen

She is a young, modem woman who doesn’t want to spend too much time on housework. She has other interests apart from cooking and looking after children and therefore welcomes any labour-saving possibility which a modern apartment with a practical kitchen and bathroom can offer.

In 1926 the heart of Germany is also being modernized. Whilst in the outside world industry is mod ernizing its production plants with the help of dollar loans and introducing Taylor systems and assembly line production, homes are undergoing not just fashionable, but fundamental, changes. In Frankfurt the prototype of the modern kitchen is being created as part of the programme to build public housing, and in particular housing estates, which city architect and planning advisor Ernst May headed between 1925 and 1930 and which became famous under the name “New Frankfurt”. The kitchen is not an extra added on to this programme but is its centrepiece. The new apartment was designed around the kitchen and home management. In order to be able to build “from the saucepan to the facade” as called for by politician E. Lüders, Ernst May engaged an expert in the city building and planning department, the architect Grete Lihotzky from Vienna.

The kitchen question in the twenties included on the one hand the social aspects of household functions, such as cooking, eating, washing, heating etc. and on the other hand the problem of different room organization of apartments which would comply with the health a n d hygiene requirements which had been introduced particularly with the cholera and tuberculosis epidemics of the 19th century in mind.

Housing misery, hunger and illness were the things which Grete Lihotzky had experienced in Vienna when she began in 1920 to design emergency and temporary housing as part of the housing estate programme; her parents died of tubercolosis in 1923 and 1924; she herself spent nine months in a sanatorium before moving to Frankfurt and the medical officer in Frankfurt had doubts about giving her a permanent contract as she had TB. “Tuberculosis was the disease which hit the poorer people in Vienna after the First World War, caused by hunger and horrific housing conditions”. Against this background it is easy to understand her energetic commitment to hygienic solutions, solutions which can equally be valued for their labour–saving qualities.

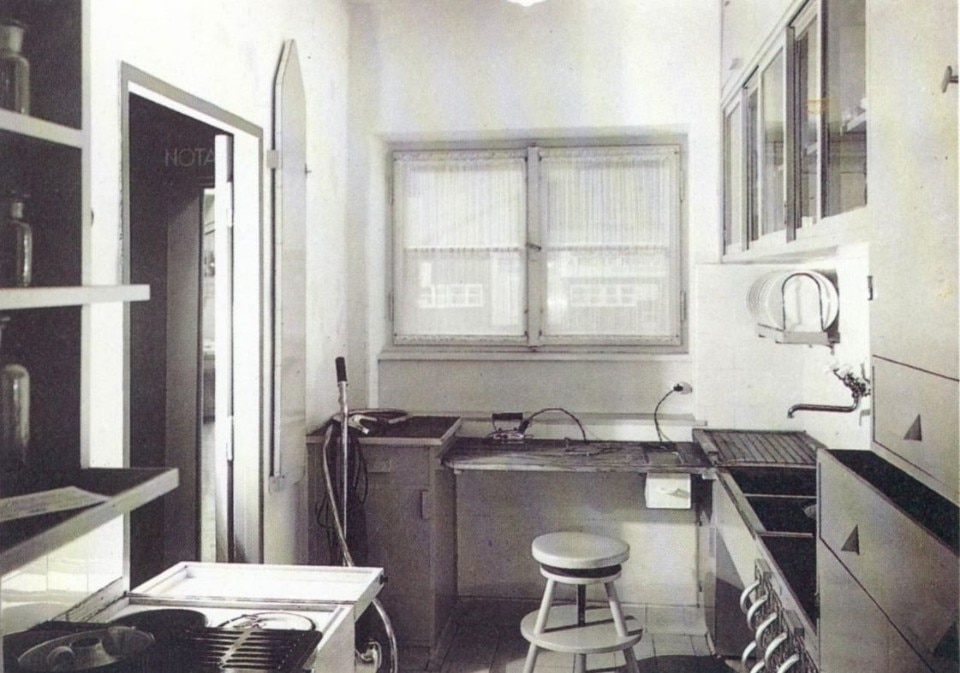

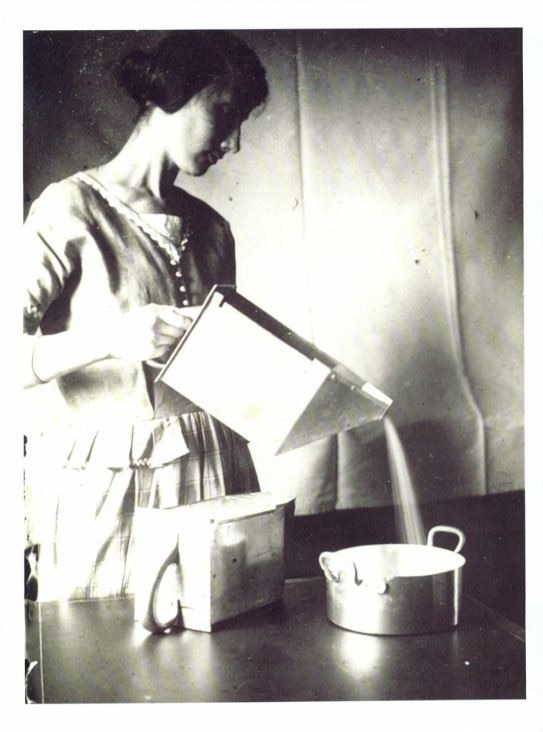

Her models for the modern kitchen type were the laboratory and pharmacy. “A kitchen is actually nothing other than a laboratory and it would be much easier to work in if it was considered as such and fitted out in a similar fashion. It has to look something like a pharmacy where every phial and every little thing has its own place or its own draw er, with a precise label, everything as far as possible the same size (...). The fitted cupboards should have glass doors, and all spices and other things such as tea, cocoa etc., which one keeps in boxes should be put into glass jars with a label just like in a pharmacy”. Aesthetic considerations are linked here to the two main motives hygiene and labour saving. This accounts for the preference not only for smooth surfaces and clear cubes but also for materials such as glass, aluminium, nickeled or enamelled metal, tiles or xylolite and linoleum.

During the First World War as a pupil of Oskar Strnad and from 1921 working with Adolf Loos, she became familiar with the most advanced concepts of modern architecture and when she came from Vienna to Frankfurt in 1925 at the age of 28 Grete Lihotzky was well prepared for her new job, having already worked for five years on the problem of the modern kitchen for the small apartment. She had the right background both with regard to methodology and social understanding when in 1922 she picked up the German edition of the book by Christine Frederick, The New Housekeeping.

Imagine the effect the American author’s research into economy of distances and movement in the home must have had on a person who was equally familiar with Loos’s “Raumplan” (volumetric plan) concept and with the concept of “Raum als Weg” (space as distance) which was being discussed at the time in the circles around Oskar Strnad and Josef Frank. Christine Frederick’s book becomes the bible of household rationalization and kitchen reform. Her German translator, Irene Witte, says in the foreword, that the author was the first woman “to transfer the principles of scientific management, which had until then only been introduced into the factory, workshop or office, to the home”. Frederick: “For every manual or intellectual task it is natural that there is an optimum and also a shortest way to do it”. Grete Schütte-Lihotzky; “We must recognize that for every job there has to be a simplest and best way of doing it which is therefore the least tiring”.

Grete Lihotzky, after her marriage to the architect W. Schütte called Schütte-Lihotzky, finished her work on the design of the Frankfurt kitchen in the summer of 1926. Parallel to this the new buildings in Bornheim and Niederrad were constructed and fitted with the first Frankfurt kitchens.

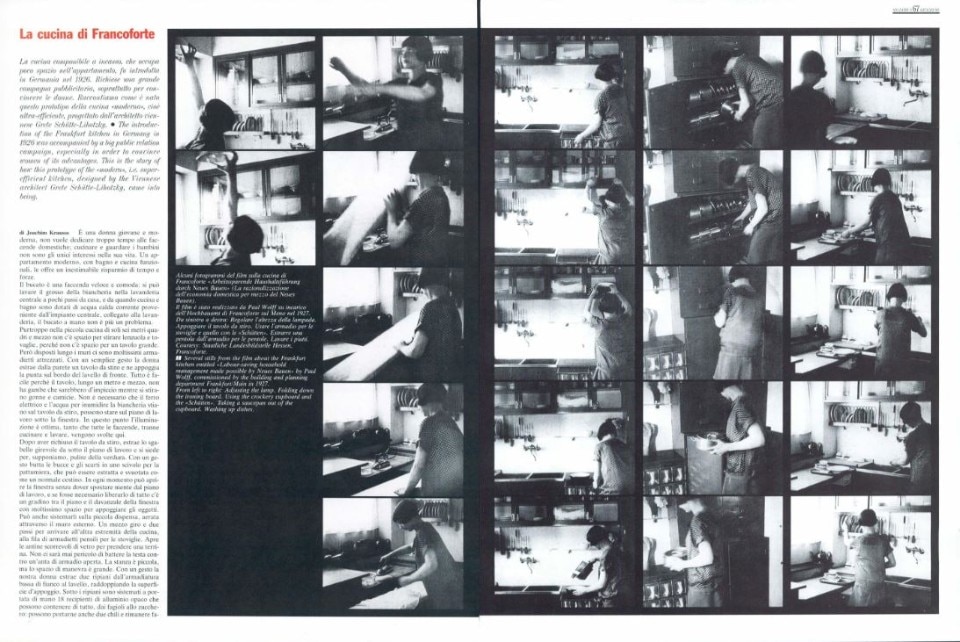

Six months later as part of the Frankfurt Spring Trade Fair an exhibition called “The new apartment and its interior fittings” was held in the exhibition hall. It was Grete Schütte-Lihotzky who was responsible for its design and realization. Attached to it was also a special show, “The modern household”, put on by the Frankfurt housewives’ association. It was meant to bring together architects, industry and women. As a particularly informative example of economy of movement and hand movements the kitchen of a Mitropa dining car with full fittings was shown. The extremely well thought-out use of space in this kitchen with adjoining pantry was impressive. The whole kitchen measured 2.90 m by 1.90 m. The passage between the cooker and kitchen table was 90 cm wide. In the course of a 15 hour journey, meals and drinks for over 400 people were prepared with no change of staff. It was obvious that the staff in these two rooms, measuring together 8 sq. m., could never have achieved such a capacity if they had had to constantly walk up and down in a large space.

Grete Schütte-Lihotzky’s comments: “Kitchens in normal apartments are usually 10-16 sq. m. There is absolutely no justification for having double the space for a 20th of the work”. The reduction of the apartment is, of course – quite independent of Taylorism – the expression of the economic necessity which had been exercised on the apartment and to which the kitchen also fell victim. Opening up, optical shortening of length and height and plastic articulation of the space had to be achieved with the long, narrow kitchen.

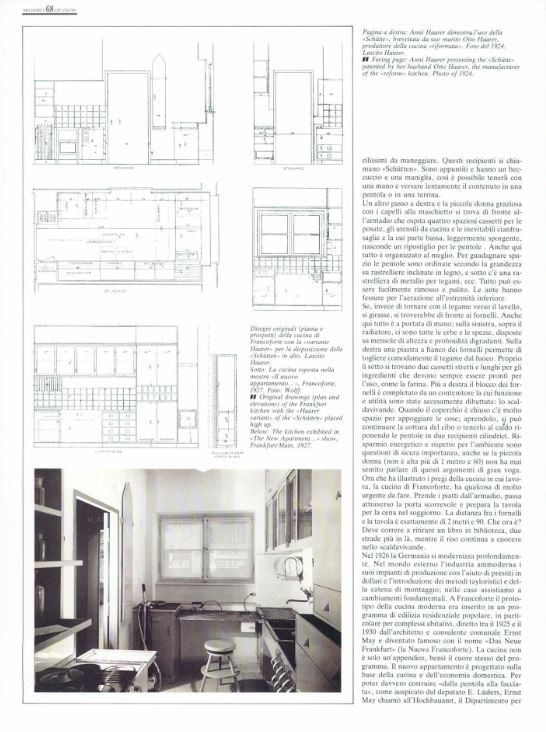

“The sliding door, which was only closed if the contact between the cooking area and living area was not desired, something which happened quite rarely, the cupboards which were only on one side of the kitchen and only sometimes had wall cupboards above them, the upper, white plasterboard part, the white extractor hood, the light-coloured tiles, the large window, the way the room widened out towards the light – these things were all ways of changing the optical impression of the room’s proportions (which is important given a width of 1.90 m). The colour combination of ultramarine woodwork (flies avoid blue) with the light grey-ochre coloured tiles, the aluminium and white metalwork and with it the black horizontal surfaces of the floor, work surfaces and cooker meant that these kitchens not only had labour–saving qualities but were also cosy places which were pleasant to sit in “The architects’ new kitchen design” was preceded by a series of attempts by manufacturers to design a new kind of kitchen furniture and household appliances. It is significant that it was not people from the field of arts and crafts who came up with new solutions but engineers. One of these was Otto Haarer. On the strength of a number of patents and a “reform” kitchen which he had designed (as an ensemble of kitchen furniture) he founded along with his brothers a firm in Frankfurt/Main. A good year before the Frankfurt kitchen was finished, the firm Gebr. Haarer exhibited its products at exhibitions for housewives and at agricultural shows. It was through Ernst May, who met the couple Otto and Anni Haarer at one of these exhibitions, that the collaboration with the Frankfurt building and planning department, and more precisely with Grete Lihotzky, came about.

Although the architect and the engineer claimed to be working on the same intellectual basis in their designs they arrived at different arrangements. The arrangement of the “Schütten” in the Frankfurt kitchen was, like many other things, a point they argued about. Otto Haarer and his wife Anni wanted to have the aluminium “Schütten” higher up out of the children’s reach and further away from the wet area of the sink. The only still existing original plan for the Frankfurt kitchen found in Haarer’s possessions after his death shows an alternative design of this kind. The cupboard with the “Schütten” has here, unlike the original version, been integrated into the pan cupboard whilst six wooden drawers have been moved down next to the original in the lower cupboard.

The decision taken in Frankfurt about the new kitchen form fell against the combined kitchen/living room. The significance of this decision goes beyond the concrete case in question because it was responsible for the creation of a new apartment prototype. And this prototype is only the cultural form of a more far-reaching turn around in thinking which was triggered off by energy supply and developments in sanitation and hygiene.

Grete Schütte-Lihotzky said in retrospect: “At the time all the things which by today’s standards make a kitchen really clean and hygienic didn’t exist. That was why the kitchen/living room was in our eyes a lower form of living because everything, the filth, the dirt, the vegetable cleaning, the peelings, the refuse, was all in the living room. That made it a lower form of living. And so we thought about this in Frankfurt and it seemed to us that a higher form of living would be created if it were possible to close off the room. But the advantage of the combined kitchen/living room was that the distance from the cooker and the sink to the dining table is extremely small, exactly the same size as it should be according to the calculations I made in Frankfurt at the time, that is to say not more than 2.75 metres. If the distance is not greater than that, if the woman in her cooking kitchen can at the same time keep an eye on the children, but if we also make a sliding door so that we can close off the room then we have combined all the advantages of the kitchen/living room with the advantage of a separate room for the dirt, kitchen refuse etc. And that was the point of departure for the Frankfurt kitchen.

A few pages later Grete Lihotzky describes the characteristic quality of the Frankfurt solution as being that: “All the kitchen are, for economy of labour, small and can be completely separated from the living space. The old form of living room and kitchen in one seems to be completely out of date”. A year later this attitude to the kitchen problem was firmly fixed in Ernst May’s mind: “Basically the so-called kitchen-cum-living-room was rejected on the grounds that it was contradictory to the modern way of living and replaced by the dual unit, fitted kitchen/living room”.

Trends showed that the specialist from Vienna was right. The further development of apartment types confirmed the use of a separate cooking kitchen as did developments in lifestyles which can be traced in the way rooms were really used and in the history of furnishing. Not until about 50 years later, when the separate cooking kitchen had established itself in practically every household, did the loss which went hand in hand with the separation of living and cooking space begin to be felt.

In the same year in which his former employee designed the Frankfurt kitchen, Adolf Loos defended the living room/kitchen with the words: “...the more high-class the establishment one dines in the more they cook at one’s table. I ask myself why the working class should be excluded from this nice thing. A thousand years ago every German ate in the kitchen. The whole Christmas festivities took place in the kitchen; it was the nicest and most suitable room (...) Everyone knows very well why children like to be in the kitchen best of all. Fire is something pleasant. The warmth of the fire penetrates the room and the house, none of the heat gets lost. The kitchen heats the whole house and the fire is what it should be – the focal point of the home (...). For all these reasons I build living room/kitchens which takes pressure off the housewife and lets her participate more in the rest of the apartment than if she has to be in the kitchen all the time when she is cooking”.