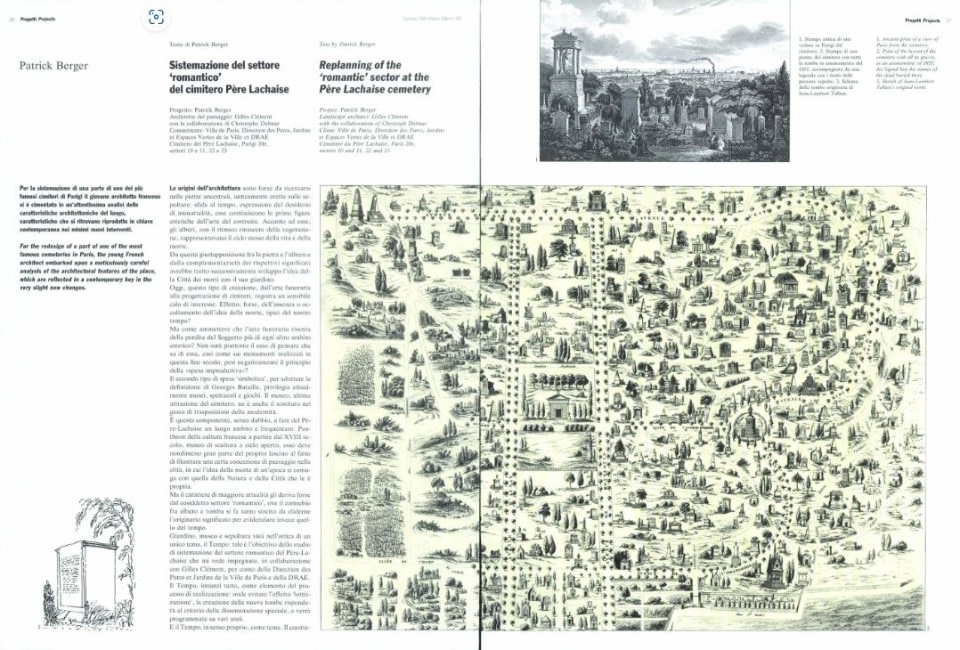

Père Lachaise hardly needs the qualification of a cemetery, so famous is it in the world that perhaps its very preponderant nature is that of a place, of an entity with a spirit, unique and unrepeatable, evoking different emotions in each different spirit passing by. From its establishment, wanted by Napoleon in 1803 to permanently replace the Cimetière des Innocents in the center of the city, to the last decades with the kissing marks on the tombstones of Oscar Wilde and Jim Morrison, what had been a garden linked to the presence of François d'Aix de La Chaise, confessor of the Sun King, has been charged with a historical stratification of meanings, between battles of the Paris Commune and illustrious guests, which the architecture and landscape ended up embodying. In 1995, for the rearrangement of the “romantic” section of the cemetery, “where the combination of tree and tomb shed their primary sense to emphasize that of time”, French architect Patrick Berger and the great theorist of the third landscape, Gilles Clément, carried out a puntual and minimal intervention that would intertwine with the dense layering of suggestions of a cemetery that has become a place. Domus published the project in March of that year, on issue 769.

Replanning of the “romantic” sector at the Pére Lachaise Cemetry

The origins of architecture may perhaps lie in these ancestral stones erected on burial-places. They are the first aesthetic figures in the art of constructing. Next to them, trees represented the cycle of life and death. From this union of stone and trees, and their complementary meanings, there later developed the idea of a City and Garden of the dead.

The present has witnessed a declining interest in funerary art and the layout of cemeteries. Is this due to the absence, or concealment, of an idea of death typical of our time? Has funerary art more than others suffered the loss of a Subject? Or is it to be supposed that, like the monuments built at this end of the century, it is avoided on account of its being an “unproductive investment”?

The other type of expenditure, which Georges Bataille defines as ‘symbolic’, today favours museums, entertainment and games. The museum, as the cemetery’s latest attraction, is also its substitute in the play of transposition of modernity. It is for this reason that the Père-Lachaise is a favourite and frequented spot: as a Pantheon of French culture since the 18th century, and museum of outdoor sculpture, it is also fascinating as a landscape within the city, where the idea of the death of an epoch is associated with that of Nature and City. But what makes it most significant today is perhaps its ‘romantic’ section, where the combination of tree and tomb shed their primary sense to emphasize that of time.

Garden, museum and burial are seen to have Time as their common theme, and this provides the key to the refurbishment study of the romantic section of the Père-Lachaise. Time first of all: in order to avoid the “allotment effect”, new graves will in future be scattered, in a layout to be programmed over a period of years.

And Time, in the strict sense, as a subject. The labyrinthine character of this corner of the cemetery led us to choose a principle of time sequences. Each of these will serve to add legibility to the effects of history and chance upon the constructions and vegetation. As the density of burials increased, the original layout by Brogniart was effaced by a maze of Gardens within the Garden, and of architectural motifs in the necropolis. These spaces, not conceived, but brought about by time, have a latent ‘unfinished’ character, which we propose to bring out and enhance, by adding a particular type of tombstone, or steps, or treatment of vegetation. Examples can be observed in the 10th ground.

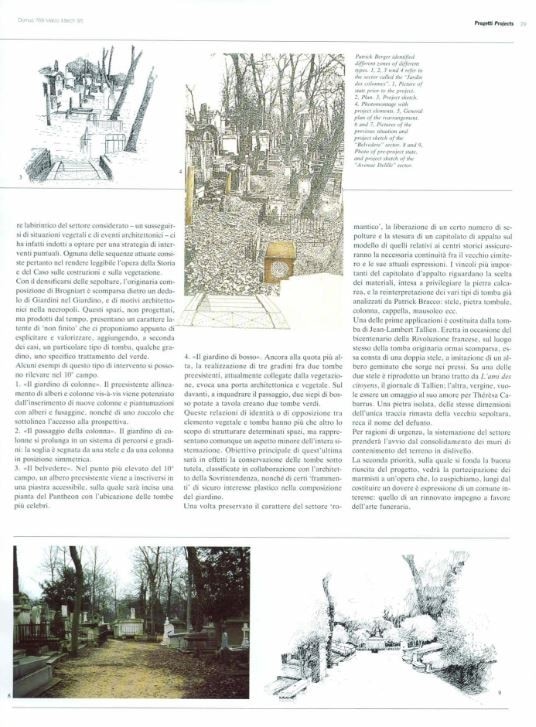

1. “The garden of columns”. The vis-à-vis alignment of existing trees and columns is reinforced by the creation of further columns and plantations of trees and spindles, and by a socle indicating access to the perspective.

2. “The passage of the column”. The columned garden extends into a system of paths and steps, the threshold being marked by a symmetrically arranged stela and column.

3. “The belvedere”. On the highest part of the 10th ground, an existing tree is enclosed by an accessible slab, on which will be carved a plan of the Pantheon indicating the cemetery’s most famous graves.

4. “The box-tree garden”. Again on the highest level, the creation of three steps between two existing graves, at present connected by vegetation, evokes an architectural and natural gateway. Framing this passage in the front are two box-wood hedges, cut in the shape of green tombs.

These associations of identity or contrast between nature and the grave serve mainly to structure certain spaces, but they are only a minor aspect of the new layout. This will rest essentially on the preservation of tombs classified by the City Council architect, and of fragments’ of plastic interest to the general arrangement of the garden. Once the character of the romantic sector has been thus preserved, the clearing of a number of graves and the drafting of contract specifications, of the kind applied to historic cities, will ensure a proper continuity between the old cemetery and its present expressions.

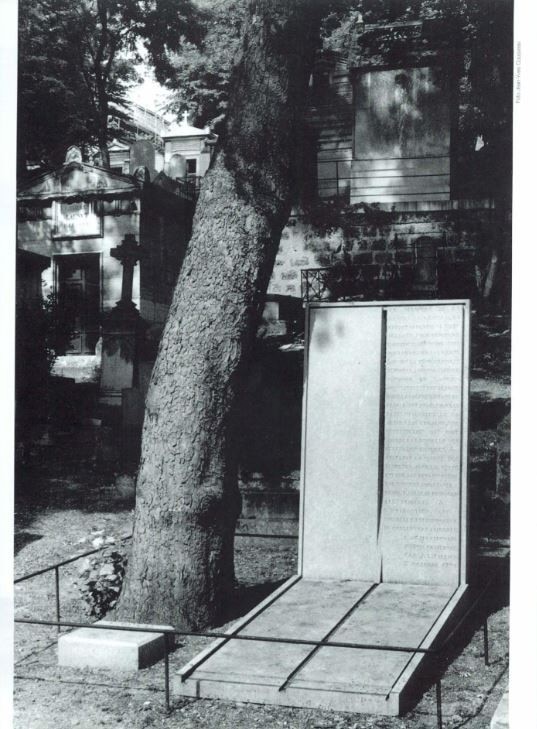

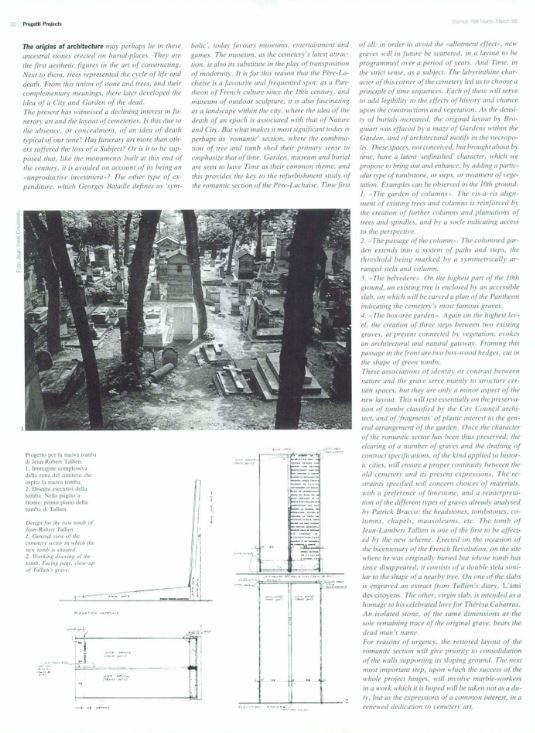

The restraints specified will concern choices of materials, with a preference of limestone, and a reinterpretation of the different types of graves already analysed by Patrick Bracco: the headstones, tombstones, columns, chapels, mausoleums, etc. The tomb of Jean-Lambert Tallien is one of the first to be affected by the new scheme. Erected on the occasion of the bicentenary of the French Revolution, on the site where he was originally buried but whose tomb has since disappeared, it consists of a double stela similar to the shape of a nearby tree. On one of the slabs is engraved an extract from Tallien’s diary, L’ami des citoyens. The other, virgin slab, is intended as a homage to his celebrated love for Thérèsa Cabarrus. An isolated stone, of the same dimensions as the sole remaining trace of the original grave, bears the dead man’s name.

For reasons of urgency, the restored layout of the romantic section will give priority to consolidation of the walls supporting its sloping ground. The next most important step, upon which the success of the whole project hinges, will involve marble-workers in a work which it is hoped will be taken not as a duty, but as the expressions of a common interest, in a renewed dedication to cemetery art.

Opening image: Cimetière du Père Lachaise, 2016 Photo oudjat45 on Flickr