Along a career that lasted from the 1930s until August 27, 1973 – the day of his death shortly arrived after the inauguration of his last work, the Teatro Regio in Turin – Carlo Mollino built his figure as a designer on an alternative position to modern or pure historicism: aestheticization of references, decoration, a quintessentially Turinese eclecticism, maximum expressiveness in interiors, such as that of his personal home, destined to become an aesthetic fetish of recent years.

But also an immediate relationship with nature as both implicit and explicit interlocutor for his projects, as inspiration for shapes and materials. We see this in so many of his interiors, and his later celebrated furnishings: it is there that Gio Ponti’s attention would soon focus, giving space from the very beginning to Mollino’s peculiar position, even in critical contributions, such as Carlo Levi’s on Casa Miller. Houses are also featured on Domus, however, and the nature they refer to is initially seaside or hillside, preceding the mountain environment that would then mark the architect’s later career with its presence. Mollino’s first project on Domus appears in November 1936, issue 107: it is a house, a seaside residence in Forte dei Marmi; then in February 1943, issue 182, comes a concept, developed for Domus itself, for living on the hillside contemplating Turin, already showcasing all the characteristic elements of Mollino’s design.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Architecture and Nature: a house in the Forte dei Marmi pine forest

The house stands in the middle of the pine forest: therefore, light had to be obtained mainly from above, towards the free sky. On one side, looking south, towards the sea, the house opens, establishing a contact between the interior life and the more joyful nature on the outside, with a passage from a porch. To the north, on the other hand, it opens directly, toward the pine forest and the Apuans.

The materials are usual, countryside-sourced. Wooden rafters; tiled roof with all around a crown, wide enough, of glass tiles that precisely give the right lighting to the rooms below. The side windows thus lose their importance. A few concrete beams and a not too generous application of glass cement to light the central living room show that Mollino carried out an idea with all objectivity, applying new materials to the extent strictly necessary and employing the usual ones where these could perfectly serve.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The result is a building where the architecture succeeds in being modern because of its excellent functionality, because of the special sensitivity with which volumes are envisioned and surfaces treated (the opus incertum is in fact seen to serve as a “surface”), and where the familiar intimacy and reflection of the scholar and artist who will live there find a perfect and very clear setting.

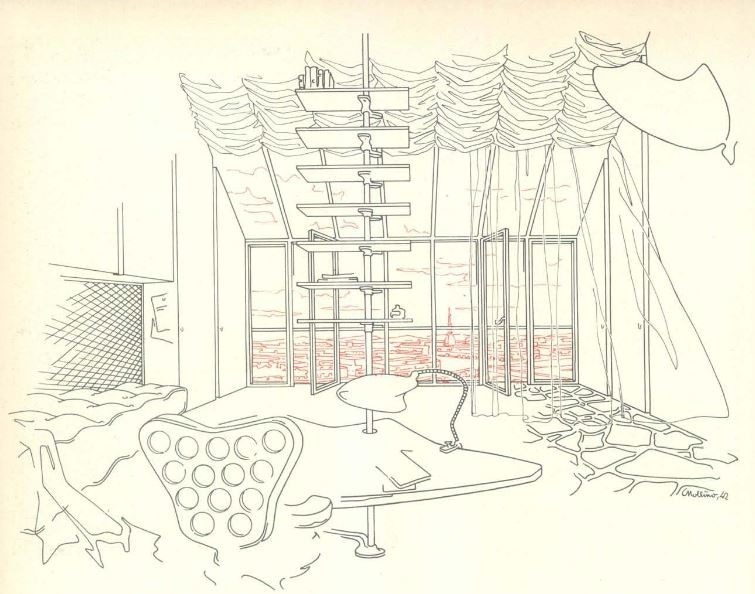

The House and the Ideal: a house on the hill

What we publish here is the letter that accompanied the project, a letter to a friend then, to explain, with all the spontaneity that a letter to a friend allows, the idea from which the architect was moved to design his house and the result that was formed from that idea. We publish it convinced that more than any other comment, it may serve as clarification to our readers.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Dearest, I sent last Thursday seven boards and four perspectives of the ‘house for me on the hills’ studied for Domus. However, I must first confess you that, personally, apart from the daily Homeric silent struggle with my father whom I love very much, I do not wish to change the environment in which I live and work at all: the office is a faithful copy of a Dutch trade office; the house a prodigious superimposition of ways of living and thinking from the Umbertine to the late Flora style, together with all the ramifications that the total absence of taste concerns can generate. If I were left alone, I would not change a chair; the environment is as neutral as I could wish for: it does not disturb me, it does not drive me to mistakes, it leaves me free instead, to be alone with my imagination, let’s call it my inner landscape to set the tone of speech.

Only that ceaseless sense of slight nausea necessary to prevent acceptance, settling down, remains perceptible. Thus, should I build a house for myself, had I the necessity, I would start from the principle of not disturbing, of leaving myself free to move and evolve in spirit, while conceding to my present taste as little as possible, aware that the Platonic sphere of the achieved work still ends up coinciding with the present fact of taste.

The environment is as neutral as I could wish for: it does not disturb me, it does not drive me to mistakes, it leaves me free instead, to be alone with my imagination, let’s call it my inner landscape to set the tone of speech.

Carlo Mollino

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

But the matter is another, and that is not to affect the future poetic fact, necessarily different from the present, with the overbearingness of an environment. This is the only and ultimate expressive problem of houses designed by architects for themselves, we can say, still: the internal and non-logical needs, in functional terms, of a house developed in height are obvious – on each floor it is me, myself and I as an independent unit – on the top floor – in the library – I am like in a Zeppelin – considering that a rational house lying in steps on the hillside would not have given me any satisfaction: on the hillside, buried in greenery, I would have thought of myself as a half-dead snake, lying on my belly and camouflaged in fear.

Given my needs, this is how the announced “trunk house” came up, very expensive, uncomfortable according to the common understanding, cramped; living in the tower (not the ivory one) is quite a clear fact for all of us: I would say it is the house that would suit a nice insect, a green grasshopper for example. But why do I keep giving reasons? You asked for a house for myself, didn’t you? Well I have conscientiously and seriously studied a buildable, workable house that I would make for myself tomorrow if I could.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

For me, the house must have a closed, independent, but also provisional character. I need a harmonious shell – it is fine – but it must not give the sense of final and locked to a mental position – this is the content to be resolved in plastic facts. And then what is of interest? Is the plastic fact resolved? That is the important thing. The only thing that has to concern me is the quenching in expression of the obsession with these forms that remain mysteries until you have finally completed them as you wished – and as you felt was dutiful and inevitable.

But I do not wish to be misunderstood: given the poetic reasons for this standing trunk the conviction remains in me that I did not make an academic project – as it could have been so easy to do. This project in execution would not be subjected to variants – those variants we see happening too often between the purity of a self-pleased graphic and constructive necessity. This is what I always kept in mind: architecture is already an unbreakable reality in the graphic realm.

I do not think it is necessary to add too many technical notes – the elevator is fast. An automatic system makes the opening of the cabin door simultaneous when the second cage door is opened: a single movement. The walls are entirely formed by the furniture and cabinets – sequences of cabinets go up from the ground floor to the top floor of the library. This house is a shelf that must not bore. The walls are insulated with the most expensive and efficient thermal and acoustic insulation. Some furniture is allowed in the proper sense of the word, i.e. trunks on trestles.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The heating is provided through heating plates – the fireplace on the second floor is a habitable and scenic little room, and the type of brazier and hood is the type commonly used in Val Gardena – still the appositely small room of the brazier-hood compartment has no dispersion system.

On the top floor, in addition to the wall shelves – closed library (see perspective) – there is a curvilinear table pivoting around a metal upright bearing shelf tops accessible by means of “pedals”, or shelves. I constantly need certain “stuff” under hand, accessible and visible – we all need such organized clutter. The skylight ceiling is shaded by the traditional curtains of the old-time studio of photographers, painters, etc. They will fill with dust – I don’t care. What I would like to be clear about is my desire to have this glass booth. Shadable and concealable by means we all know. One does not always want to have the city and the view at their feet. A cabin with a panoramic glass window, and not a greenhouse for a steam room. The costs to refrigerate such a room, I will afford them with serene generosity.