To be precise, all of Christo and Jeanne-Claude's ages since they met in 1958 have been golden ages. By the 1990s, by which time their pairing was a trademark associated with urban-scale and land art works known to a very wide audience, the two artists had already “wrapped” the Pont Neuf in Paris and the Reichstag in Berlin, and would continue with a long series of works capable of outliving both of them, with the great collective work of wrapping the Arc de Triomphe (2021), and the Mastaba for the United Arab Emirates now awaiting completion. The portrait that Pierre Restany published in dialogue with the couple in February 1997, on Domus issue 790, is also a portrait of an entire sequence of seasons in modern and contemporary art.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Christo e Jeanne-Claude, The great veil of wonder

New York, 16 December 1996, 5 p.m. Christo and Jeanne-Claude receive me at their home in Soho, a stone’s throw from Canal. The first landing of their building is the communication floor. Facing their sitting-room, a long wide partition bears the panels of their latest project in progress: “Over the River”. We had fixed our appointment by fax from Milan and they were expecting me. The gap they generously provided for me in their timetable is a festive interval. They are radiant, he and his beaming smile, she dazzling with her shock of red hair. After a tour of our souvenirs we come in medias res, to the “oggetto rivestito”, the object clothed, which is the transversal theme of this number o/Domus. No sooner do I broach the subject than Christo nods to show me some of the items dating from 1958-59. Resting on a stela in a transparent plastic box, are the first “wrapped objects”, done when he arrived in Paris. It’s all there already, he tells me, and the film of the prehistory of Nouveau Réalisme begins to flicker through my head: to Yves Klein the void, to Arman the fullness, to César the compression, to Christo the empaquetage...

The cloak renders the essence.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Making packages is like expressing yourself by appropriating reality with everyday materials within easy reach, in a rapid and definitive act, just as in the stripping of posters or compressing of scrap metal, confirms Jeanne-Claude. Christo approves but lifts the debate at once, from wrapping to drapery. The important thing is the drapery: the fabric covering up this or that volume is what reveals the deeper truth of form. Jeanne-Claude regales me with a march-past of details of drapery borrowed from every period in the history of art. “When we give lectures on our work, we always start off with that.” And we never forget, adds Christo, to quote the famous anecdote of Rodin’s Balzac: the first version of the sculpture represented Balzac in the nude, with all his anatomical details. In the second version, the final one, Balzac’s body is enveloped in a cape that eliminates the details and effectively plays the part in his characteristic posture. And Jeanne-Claude concludes: “The cloak renders the essence.”

The discussion continues at this alternative pace of compensation and higher bidding, so well that the couple very soon give me the impression of being a sole interlocutor, the two parts of a same whole, the simultaneous vectors of one and the same perspective thought. An operational osmosis of the kind could not but lead into the common property of their work. How long is it since you started signing your projects together? “Since 1994. But that decision merely ratified an established situation that had been going without saying for a long time.”

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

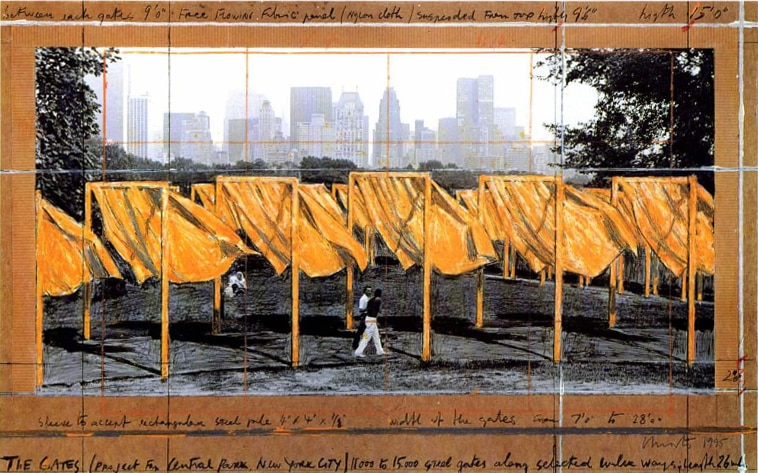

We go back now to the drapery, the wrapping, and to the core role ascribed to it by my two protagonists in their joint operations. “The drapery sets the measure of the project’s ephemeralness.” The transitory dimension is what distinguishes the “Christo/Jeanne-Claude” project philosophy, its truly vitalist anchorage. “Life does not last.” Christo and Jeanne-Claude spent fortunes of energy, technology and money to wrap the Pont-Neuf, in Paris in 1985, to package monuments like the Victor Emanuel or the Leonardo in Milan for the 10th anniversary of Nouveau Réalisme (1970), or again, to wrap the Reichstag in Berlin in 1995, or one million square feet of coast at Sydney (1969), to stretch a curtain between two mountains in Colorado (“Valley Curtain”, 1970-72), or again, to run a nylon fence across northern California (“Running Fence”, 1976) 40 kilometers long, or simultaneously plant 1340 blue umbrellas in Japan and 1760 yellow umbrellas in California (“Umbrellas”, 1991).

These projects last only a few days, after which the second skin applied to their sites disappears, as it is inexorably destined to do. “What we want to create in our work, through the transitoriness of wrapping, is a quality of love and tenderness towards the transitory and the ephemeral, which are the laws of life.”

Our self-financed and entirely recycled works are the expression of the purest creative freedom; the manifestation of poetry at liberty can only be temporary, that is life!

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

All the projects by Christo and Jeanne-Claude take a considerable time to prepare and develop. They have reference to the global environment of life, unlike ‘normal’ works of art, which define their own space. And that exterior environment is of an extreme complexity, technical, ecological, semantic and symbolic, socio-political and financial. When Christo and Jeanne-Claude start acting on a site, they create what they call a “gentle disturbance”. They have to convince the owners, lease the land concerned, and forecast every even smallest consequence of their action. Nothing is left to chance, nevertheless they are not immune to the whims of nature, as was the case of the “Valley Curtain” or of the “Umbrellas”. They come up, too, against the formidable barriers of politico-administrative formalities. Conceived in 1975, the Pont-Neuf project was carried out in 1985. It took them 24years to realize the “Wrapped Reichstag”, from 1971 to 1995, and only a vote in the German parliament finally enabled them to unblock the situation. Their energy and tenacity are measureless. The Reichstag project entailed a myriad of preliminary steps, quite apart from what amounted to actual political lobbying. Their global style of environmental action arouses both unconditional support and the most diehard opposition. Before the Reichstag project was completed in Berlin, Christo had to permanently wear a bulletproof jacket, due to the death threats he had received. And that can be hard to believe when one has witnessed, as I did, the triumphal welcome it received from the Berlin crowds, and their explosion of collective wonder (Domus 775/95).

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Yes, the logistics of wrapping is a complicated business. “The big problem for the critics is the interpretation of our work. They do not understand it in depth, as on the other hand architects and urban planners do. It is easier to build a building than to wrap it! Before we could plant our umbrellas in Japan, we had to obtain permission from the Japanese ministry to build 1340 homes.” One umbrella = one home; it makes you think.

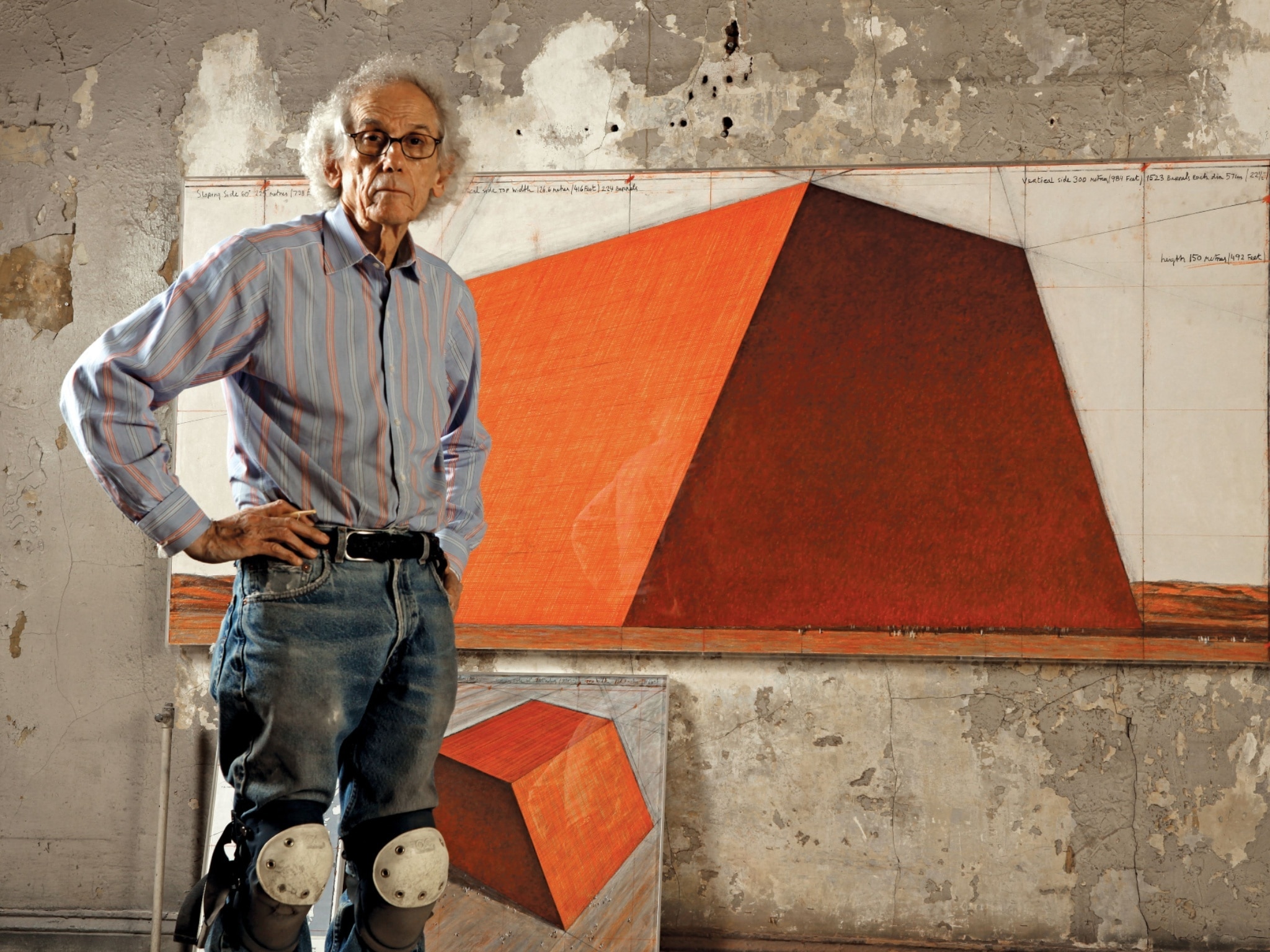

Their technique is colossal, both in its precision and in its scale. The packaged air at the Documenta in Kassel in 1968 was 5600 c.m of wrapped immateriality. The Reichstag in 1995 involved 100,000 sq.m of silvered polypropylene, 15600 m of blue rope, 200 tons of steel... It is in tens of millions of dollars that the cost of their most recent enterprises can be counted. The financial coverage of the operation is entirely ensured by the sale of Christo s works, past present and to come (preparatory drawings, lithos, collages...). This is the province of the C.V.J. Corporation (Jeanne-Claude, President), which relies on bank credit, and undertakes to repay the full amount borrowed.

The temporary aspect (each project lasts not more than 14 days), the environmental, the technical and the financial aspects are an integral part of the Christo-Jeanne-Claude aesthetic and their comprehensive vision of art. “Our self-financed and entirely recycled works are the expression of the purest creative freedom; the manifestation of poetry at liberty can only be temporary, that is life!”.

“Christo and I”, adds Jeanne-Claude,” lie in wait for the performing idea, and when it materializes, we decide to get pleasure out of it. And that is when the mechanism gets into motion, the toing-and-froing between the idea and the site and between the site and the idea, leading up to its ultimate fulfilment. In this existential perspective there exists, to be sure, a division of work: we never take the same flight, Christo does his drawings alone, and ignores all the accountancy. But there also exists a common vision: the pleasure of creating in freedom.”

8 p.m. I leave with regret the wings of this extraordinary enterprise of ordinary wonder. The Christos have gone down into the legend of our century through the paths of pleasure, and they certainly have every intention of continuing to give themselves pleasure in this way. Their next projects include both the resumption of the “The Gates” (Central Park, New York) conceived in 1979, and the implementation of “Over the River”, a project for the river Arkansas in Colorado, on which they have been working since 1992. When will either of these be ready? Not before 1999 or maybe later. But nothing in the year 2000. The planetary scene will be too cluttered...