It was the late summer of 1969, 55 summers ago, when multiple events and scenarios intersected, their context being crucial for the world and for a city that embodied its balance – Berlin – as it was for architectural history and global and local political history.

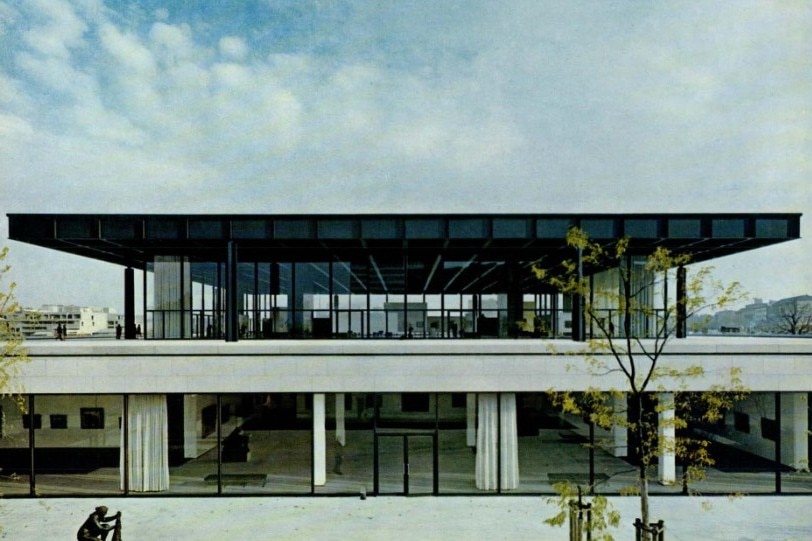

On August 17, Modern maestro Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had died, while in an area of great significance, in the heart of a two-split Berlin, still scarred by WWII bombings, a work considered as the synthesis of Mies’ poetics was completed, the Neue Nationalgalerie, monumental and abstract, classical and modern at the same time.

It is part of a vast project, the Kulturforum, which had started with Scharoun's Philarmonie, continued with Mies and then Stirling, destined to last for decades, amidst additions, subtractions and awaits (one carrying the signature of Herzog & De Meuron), still in progress. In the meantime, Mies' masterpiece has already been recently renovated by a past Domus former Guest Editor, David Chipperfield, while upon the death of the maestro it was another famous name from the magazine, Agnoldomenico Pica, who presented it, on issue 478 of September 1969.

Mies in Berlin

The pseudo-Romanesque Matthii ikirche, built by Stuler in 1845, miraculously escaped the bombardments that raged around this area just in time for its centenary. For almost twenty years it remained isolated and derelict in this blasted heath to which the area south of the Tiergarten had been reduced.

Then, in 1963, Hans Scharoun erected his now famous "Philharmonie" not far from the church. Now, with the end of doing everything possible to recreate the wonderful patrimony of art collections shattered in Berlin during the last war, it was decided to construct a new cultural centre in far West Berlin—the "Kulturforum am Tiergarten"—in this neighbourhood, to supplement the Museums of Charlottenburg and Oahlem, the Brilcke-Museum and the Berlin-Museum.

The new centre will consist of the Federal Art Library, a Picture Gallery, a Print Room, a Collection of Sculpture, a Museum of Applied Arts, in addition to buildings for the Restoration Laboratories and GeneraI Administration.

Of this exacting programme, which is to centre round the Kemperplatz, the building designed for the "Neue Nationalgalerie"—dedicated to nineteenth century and contemporary art works—has now been completed. The project by Mies van der Rohe, dating to between 1962 and '65, was already known through a publication edited by Werner Blaser, which showed it to maintain close links with the earlier project for the Sala Bacardi, Santiago, Cuba (1957) and, even more evidently, with that for the Georg Schafer Museum Schweinfurt (1960).

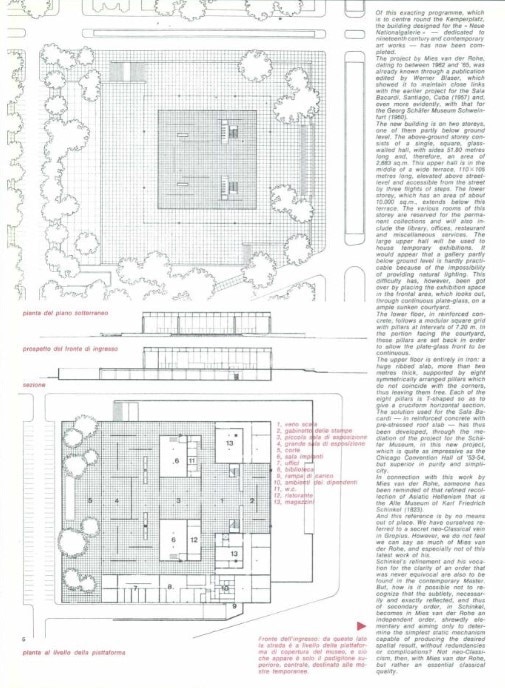

The new building is on two storeys, one of them partly below ground level. The above-ground storey consists of a single, square, glass-walled hall, with sides 51.8 metres long and an area of 2,683 sq.m. This upper hall is in the middle of a wide terrace, 110 x 105 metres long, elevated above street level and accessible from the street by three flights of steps.

The lower storey, which has an area of about 10,000 sq.m., extends below this terrace. The various rooms of this storey are reserved lor the permanent collections and will also include the library, offices, restaurant and miscellaneous services. The large upper hall will be used to house temporary exhibitions. It would appear that a gallery partly below ground level is hardly practicable because of the impossibility of providing natural lighting. This difficulty has, however, been got over by placing the exhibition space in the frontal area, which looks out, through continuous plate-glass, over an ampIe sunken courtyard.

In connection with this work by Mies van der Rohe, someone has been reminded of that refined recollection of Asiatic Hellenism that is the Alte Museum of Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

The lower floor, in reinforced concrete, follows a modular square grid with pillars at intervals of 7.2 m. In the portion facing the courtyard, these pillars are set back in order to allow the plate-glass front to be continuous.

The upper floor is entirely in iron: a huge ribbed slab, more than two metres thick, supported by eight symmetrically arranged pillars which do not coincide with the corners, thus leaving them free. Each of the eight pillars is T-shaped so as to give a cruciform horizontal section.

The solution used for the Sala Bacardi—in reinforced concrete with pre-stressed roof slab—has thus been developed, through the mediation of the project for the Schaler Museum, in this new project, which is quite as impressive as the Chicago Convention Hall of '53–54, but superior in purity and simplicity.

In connection with this work by Mies van der Rohe, someone has been reminded of that refined recollection of Asiatic Hellenism that is the Alte Museum of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1823). And this reference is by no means out of place. We have ourselves referred to a secret neo-Classical vein in Gropius. However, we do not feel we can say as much of Mies van der Rohe, and especially not of this latest work of his. Schinkel's refinement and his vocation for the clarity of an order that was never equivocal are also to be found in the contemporary Master.

But, how is it possible not to recognize that the subtlety, necessarily and exactly reflected, and thus of secondary order, in Schinkel, becomes in Mies van der Rohe an independent order, shrewdly elementary and aiming only to determine the simplest static mechanism capable of producing the destre spatial result, without redundancies or complications? Not neo-Classicism, then, with Mies van der Rohe, but rather an essential classical quality. Agnoldomenico Pica