Architettura educatrice is the title of a monographic Domus issue on the design of school buildings, published in June 1947. “It is rare for architecture to present as much adherence between form and content as it does in school buildings. A teacher's words and an architect's building collaborate in equal measure toward educating young people,” reads the editorial by Ernesto Nathan Rogers, who goes on to list the basic themes of the issue's dissertations. There are discipline and freedom (these being “the dialectical terms by which the small scholastic society is debated”); the individual and the community (“The harmony of the surroundings indubitably educates toward equilibrium in collective relations, while the clear identification of objects destined to each person confers a greater amount of dignity to the individual.”); rights (“of which the school is the most protective matrix”) and duties; economy and quality (“We need to recognise that some types of freedom cost less money than we think.”)

In the post-totalitarian and freshly democratic Italy busy clearing rubble from the war and practically still unaware of the economic boom on the verge of unfolding, architecture was an educational tool of anti-Fascism. The article by Ernesto Codignola clarifies this in no uncertain terms. One of the most renowned Italian educators of the 20th century, Codignola was first a supporter of the Fascist regime, working with Giovanni Gentile on the draft for the school reform that Benito Mussolini defined “the most Fascist of the reforms”. Then he became militantly active against the regime. His essay, definitely more trenchant than Rogers’ brief editorial, is titled Scuola, palestra di vita (“School as a preparation for life”). Written by “one of the most illustrious and combative Italian educators”, it is steeped in revolutionary impulse. “We need to commence the revolution with an external tidying up. We must erase all traces of passiveness, abolish the desks of pupils and teachers, the didactical furnishings, the text-books – all evidence of pretentious mediocrity,” Codignola writes. The deprecation of the school as it was back then, which “claims to teach liberty and individual initiative through mechanisms and slavery,” led to the glorification of an active and empowering way of teaching. The term “liberty” and its derivatives are used none less than six times in the text. “Responsibility” and even “self-governance” are considered the focal points that the scholastic institution must incorporate in order to transform from “prison” into “community”.

View gallery

View gallery

The contribution by Amos Edallo, an architect from Cremona who dedicated a wide range of studies to the specific conditions of his native countryside, is an in-depth and well-illustrated analysis of rural schools. It describes an agricultural way of life that was then still lively, but destined to undergo profound, irreversible transformations within a few years. The two following articles are dedicated to two subjects that are complementary in many ways and still very current. Eugenio Tedeschi tackles The problem of the classroom, the smallest unit of school space, and Giancarlo De Carlo, the future renovator of the university campus in Urbino, airs his views on Schools and urban planning.

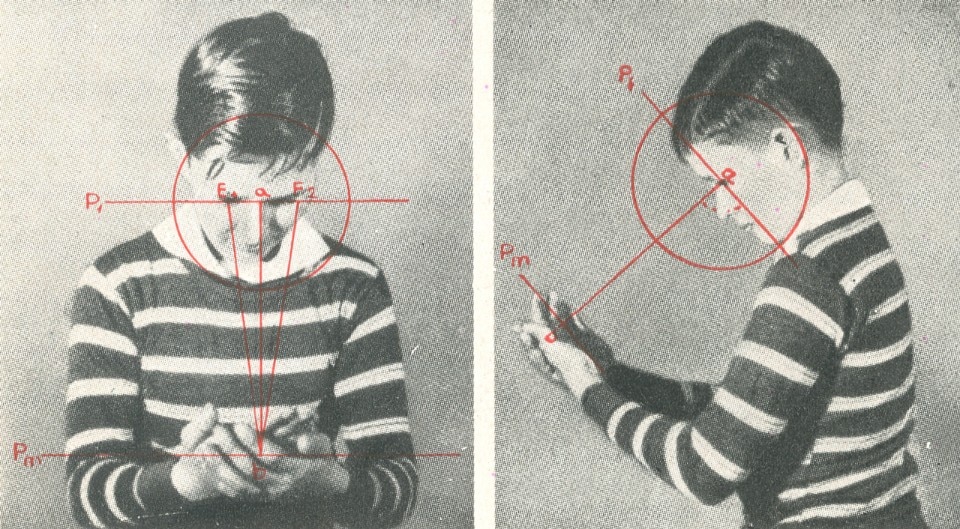

Pictures of virtuous American, Swiss and Danish examples, plus several beautiful illustrations taken from Architectural Record issue 99 (First Postwar School, 1946) support Tedeschi's excursus on the fundamental characteristics of "tomorrow's school". Flexibility, lighting, cross-ventilation and the possibility to conduct at least some of the teaching activities outdoors are a few of the environmental qualities that the author presents as indispensable standards. For a large part, they have remained unrealised from then until today. De Carlo, too, points to a number of foreign cases in Switzerland, The Netherlands, England and especially the United States as reference models offering inspiration. In these countries, advanced forms of urban planning recognise that "the urbanistic problem of schools is the urbanistic problem of the city". In De Carlo's view, the two terms end up coinciding. "The school is the nucleus of social life, closely linked to the life of the community, not limited in time and space, extended to the entire existence of the citizen and the entire environment of the city," he writes.

The cultural framework of this publication's discourse is on message. The second part of the issue reinforces its contours through a roundup of exclusively foreign initiatives. Switzerland is mentioned in the text by Alfred Roth, who dusts off the theories of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and uses them as a term of comparison to verify the success of modern Swiss schools. Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States are also referred to. The contemporary reader, accompanied by the words of the American educator Carleton W. Washburne in the discovery of an elementary school by Eliel and Eero Saarinen outside Chicago, will be interested to hear of the indoor presence of a "pioneer's room" that reproduced the living conditions of the first colonialists right down to the last detail.

View gallery

View gallery

Domus issue 220 confirms that immediately after World War II, Europe and America remained fundamental references to Italian architectural culture. Such xenophilia was cultivated above all to sever ties decisively with its immediate past of Fascism. School buildings were taken as a filter, a case study that was as appropriate as could be, by which the magazine affirms with clarity its position in the debate on the postwar reconstruction of Italy. Domus wanted to contribute to creating a country that would be “explicitly modern and liberal" starting from the schools that shape its future citizens.