This article was originally published on Domus 1086, January 2024.

Luke Pearson and Tom Lloyd run a design studio based in Hackney, one of East London’s grittier districts, and in the 19th century a centre for the furniture industry. Though they design business-class seats for airlines including Lufthansa and Virgin, office furniture for the multinational corporation Teknion, and plastic chairs, their building has the flavour of a workshop where things are crafted with care by hand.

It’s a spirit that reflects the approach they have taken for the Pupa project, which combines digital technology with the ancient craft of knitting. Unlike their day-to-day workload which is based on finding ways to deliver solutions to defined needs, Pupa was an open-ended research exercise looking at ways towards achieving a minimal carbon footprint. “We were trying to free ourselves,” says Pearson. But they see it as relevant to all their practice.

They began with a consideration of the further potential of a textile that they had previously used for the upholstery of the Revo range of workplace furniture made by Camira, a Yorkshire textile company with origins going back to the 18th century. It is made from 100 per cent recycled polyester, mostly a yarn spun from plastic fishing nets salvaged from the sea. At Camira they found the company’s capacity to manufacture three-dimensional knitted textiles, and set out to test if it could be used to make objects.

When Charles Eames began exploring new approaches to designing chairs with complex forms, he began with moulded plywood, then tried stamping metal, before working with fibreglass. They all required complex machines and tools. Digital knitting technology allows for complex forms to be mass-produced without the need for physical tools. Unlike pattern cutting from a roll of sheet material, which inevitably results in waste from the offcuts, knitting from yarn is waste-free. Their starting point was to understand the essential characteristics of the material they were working with.

Or as Louis Kahn put it, “‘What do you want, brick?’ And brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’” “We were looking at how much volume we could create with a minimum of carbon. Often designers force materials to take on a given shape, but there is no guarantee that is the most efficient form. You have to respect the material, and because we are working with a textile, you can’t force it,” says Lloyd.

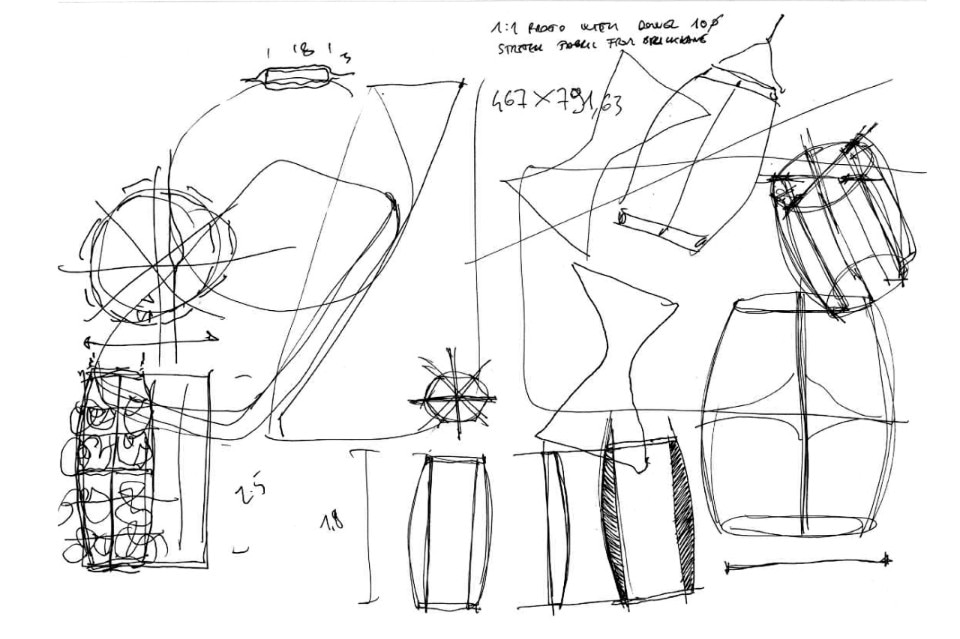

They sketched out a range of potential forms that could be achieved using fabric held in tension by timber rods, fastened with twine. In its directness and simplicity, it was a method inspired by a chair made in Mali using traditional techniques that sits on a shelf in the studio. Having explored the possibilities of the technique, and gone back and forth between Camira’s technicians, and their own models, to explore the kind of shapes they could make, Pearson Lloyd took the shapes they had worked on as a sculptural exercise and put it to work as the basis of a light fitting that they have manufactured as a set of prototypes in a variety of colours. Pearson Lloyd see it as an exercise in developing a new approach to design. In their view, formal considerations must be the product of a design method that starts from minimising carbon impact.

FADE Family is the new approach to outdoor living

The latest addition to the PLUST Collection is a line of furniture inspired by the texture of white stone, which illuminates as evening falls.