What is Google? A search engine, you’ll most probably answer. And that’s correct: “the” search engine. But Google is also YouTube, Gmail, Google Docs, the Android OS that powers most of the planet’s smartphones, and much more. And Google is not just software: it’s also the Pixel lineup of devices—smartphones, earpods, tablets, ChromeOS laptops, as well as Nest home devices such as smart speakers and displays, and more. At the head of the Google hardware design team is VP Ivy Ross, a passionate, award-winning designer and scholar who joined the tech colossus almost ten years ago.

Google had just launched Glass at the time, Ross recalls, a futuristic connected eyepiece with smart functions, and was looking for an expert eyewear designer. “In my career, I’ve designed fashion, toys, jewels, and much more. I didn’t even remember working on eyewear,” says Ivy Ross to Domus smiling, while we sit at a table in the coffee area of this year’s Google exhibition at Fuorisalone. So, “after many interviews,” she was hired. The Glass project was then closed; “it was a device ahead of its time almost a decade,” Ross explains with relaxed, slightly hoarse voice, in her almost-hypnotic tone often interrupted by emphatic laughs. So, Google let Glass go but kept Ross, who had previously held executive positions at Swatch, Calvin Klein, Gap, and more, and whose innovative metalwork is in the permanent collection of almost a dozen international museums. “I was so intrigued: I’ve always been a bit of a futurist ahead of my time.”, she comments.

The original Pixel smartphone debuted in 2016, the same year that Ross-led Design, UX, and Research for Hardware Products team at Google was officially formed. Since then, Google hardware devices have won more than 250 design awards.

At the roots of Google’s design language

“People who know me say I’m a builder”. Ivy Ross’s greatest challenge at Google wasn’t just to build a coherent lineup of hardware projects, but to create a design language for physical products in a company that had always been software-focused only. And that was a cultural challenge. One significant example is color. “When I first came to Google, I said that I needed a color lab,” she recalls. “And they said, ‘what do you mean, you have colors, it’s red, blue, and yellow…”. She smiles, remembering how she answered to that. “‘That is great for the Google logo’, i replied, ‘but we’re going to be making things that you have on your head, in your hand, in your home’”.

A relevant case history in Google’s hardware was the launch of a color called hazel. “Everybody at that time had a black phone”. But then consciousness about climate change and ecology rose, “so we said different greens will be the new black”. Hazel is a dark green coloration, almost black, and it sold incredibly well. “That’s what people were aching for, were craving for, maybe unconsciously, they may not know why, and that’s because there’s a little green in it, versus a black-black”.

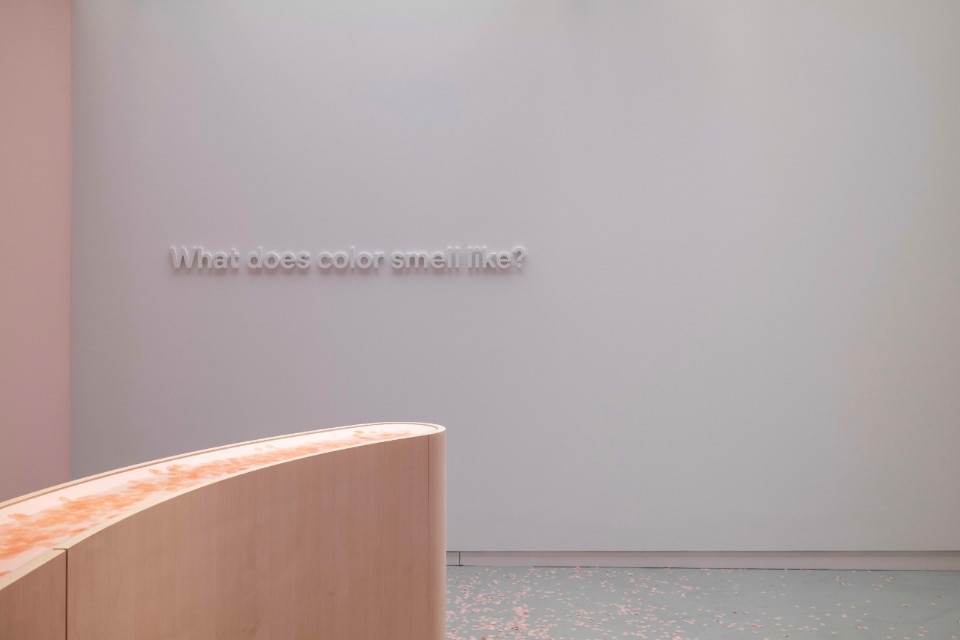

Color was also the protagonist of this year’s Google exhibition at Milan’s Fuorisalone, a follow-up to 2023’s “Shaped by Water”. Google debuted in Milan with “Softwear” in 2018 and came back the following year with “A space for being”. “I had told marketing about the Milan design show because they didn’t know it”, says Ross, who suggested to come and exhibit here, a unique occasion to work on a different scale for Google’s material design team, “the biggest invest, it takes a lot of time being here”, but also “a reward for all the hard work we do” and the chance “to share a piece of our soul”. This year’s kaleidoscopic exhibition, titled “Making sense of color”, was co-created with Chromasonics, the Venice Beach-based art lab that created the eponymous immersive experience.

Functionality is important, humans are more important

“Electronics are going to stay”, says Ivy Ross. And her task as a designer is “to make them more familiar”. Google’s approach to designing hardware prioritizes human connection. “How does this product feel?” is a key question for Ross. Product design has always been too much about functionality, and not enough about feelings, she points out. Her team’s thought process is different. “Human, optimistic, and bold,” are according to Ivy Ross “the principles that have guided all the hardware we’ve done”. Putting human back at the center, instead of insiting on mere functionality. That was the essential message of Google 2019’s exhibition at Fuorisalone, “A space for being”, where “people could understand that their body feels all the time, not just their head”.

“Since the Industrial Revolution, we’re concerned about being productive in our heads and forget about the sensorial nature of our beingness”, Ivy Ross explains. “I think that’s what beauty and aesthetics do, it is alive in your senses, and when you’re alive in your senses, you feel alive”. Our bodies, she explains, were designed to respond to this sensorial nature of life.

Nature itself is a crucial pillar of Ross’s design. Ivy Ross goes back again to the first days of her time at Google. “We looked at our competitors that we admire and we said that we wanted to be more human”. And to do that, to design for humans, Google takes huge inspirations from nature. “Nature is the most neuro-aesthetic place there is, and since art and aesthetics affect our body, when in doubt, my rule is to always refer to nature”, she says. That’s why the company’s first speaker was modeled after a river stone and Google’s first VR headset, the Daydream View, released in 2016, was covered in fabric, Ross explains. “That was a bold move. And optimistic: it was intentional. It was human, optimistic, and bold”.

Will AI make us more human?

In a conversation about technology and humanity, connection and creativity, talking about Artificial Intelligence and the emergency of generative AI programs in creativity is almost obvious. Ivy Ross introduces the topic on her own, anticipating my intentions and spoiling a couple of precise questions I had prepared for this interview. Her views are also a relevant point of view since they comes from a Google VP, a company with huge investments in AI, even if Ivy Ross stresses the fact that she’s sharing with Domus not Google’s, but just her own personal opinion, mostly based on how far she’s gone playing to understand AI capabilities. There’s been a lot of talk in town about AI, but as she points out, we’re still just experimenting with it.

We looked at our competitors that we admire and we said that we wanted to be more human.

Ivy Ross

“I’ve tried it for imagery, but I don’t use it for that”, she comments. “I do use as a base for certain information. It’s a good starting point”. AI is a great foundational tool, according to Ross, “but you have to add the human piece”. That’s why on a wider scenario she considers Artificial Intelligence “as a good thing”, because it forces “to be more imaginative and creative as humans”, and “to add something to this technology and bring it to a new place”. Things will eventually change in the future, she observes. “But I think that only humans have the ability to imagine things forward”, she adds. And the future outcome will be that “we’ll be copiloting at the end”, but before this, the machines will have to learn to do their job, “and we need to do ours”, that is, according to Ross, “understanding our creative and imaginative abilities so that we can bring something new to the machine”.

But that’s a future that still looks far away. On a shorter schedule, we expect the new Pixel 9 lineup to be launched before the end of the year and hope to welcome back Google at Fuorisalone 2025.

Opening image: Ivy Ross. Courtesy Google

Sahil: G.T.DESIGN's Eco-conscious Design

At Milan Design Week 2025, G.T.DESIGN will showcase Sahil, a jute rug collection by Deanna Comellini. This project masterfully blends sustainability, artisanal craftsmanship, and essential design, drawing inspiration from nomadic cultures and celebrating the inherent beauty of natural materials.