Melchiorre Bega (Crevalcore, Bologne, 1898-Milan, 1976) is a prominent figure of 20th century Italian architecture. Whereas the writing of histories has not made him a full-fledged protagonist, still throughout his five-decades-long career he had the occasion to cross and interpret the main movements and ideas of his times – from the 1930s rationalism to the 1950s international style and later on even brutalism, though peripherally – and to get in touch with first-tier intellectuals, such as Gio Ponti.

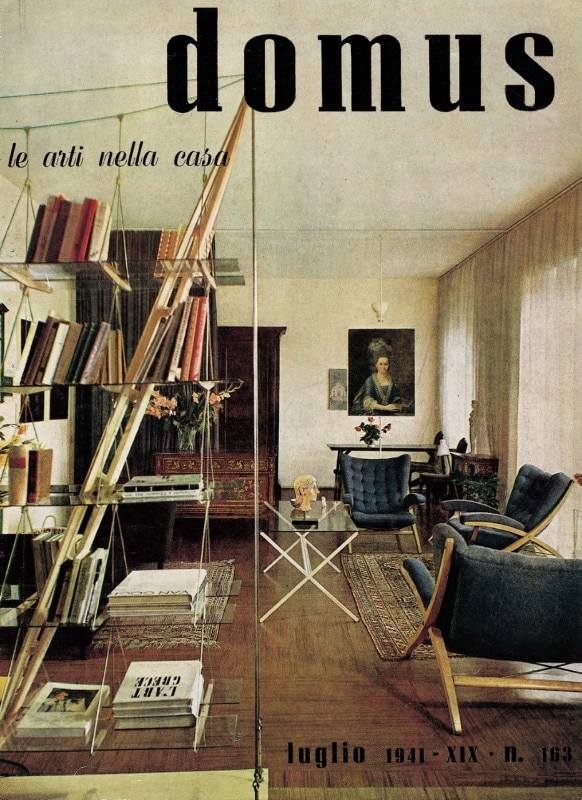

Already in the 1930s and the 1940s, it is precisely Ponti’s Domus that gives extensive consideration to Bega’s projects, which are mostly upper-middle-class residences in Milan, Bologne and Rome. Casa Dellepiane (1939) and Casa Galimberti (1939), both in Milan, as well as the R. apartment in Rome (1942) well exemplify his cultivated but pragmatic approach, anything but radical. In fact, he integrates a few elements of a rationalist-inspired modernity – in this regard, see for instance the sculptural volume of Casa Dellepiane’s inside staircase – within domestic interiors that are all-in-all traditional, both for their materials and for their space layout.

Single-family houses such as Villa Pace (1940), the Villa in Lodi from the same year and even the residence that he builds for himself on the hills surrounding Bologne (1941) confirm his non-purist approach, combining a certain strive towards abstraction and simplification, shown by the absence of decoration, with the revival of vernacular elements. The latter include double-pitched roofs and the use of traditional materials, such as for his architectures’ basements, often clad in cut stone.

His first cafés, showrooms and pavilions also date back from the same age, and reaffirm Bega’s eclectic character. It allows him to span from the monumentality of the Grande Italia café in piazza dell’Esedra in Rome (1938) to the metropolitan, futurist-inspired fascination of the Motta showroom in Milan (1934), and even more so of the Perugina pavilion at Milan trade fair (1934), that is an interesting example of a dialogue between architecture and typography, typical of those years.

View gallery

View gallery

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Alberto Legnani, Giorgio Ramponi, Casa appenninica at the Triennale, 1931. Photo Crimella. From Domus 47, November 1931

Melchiorre Bega, Alberto Legnani, Giorgio Ramponi, Casa appenninica at the Triennale, 1931. Photo Crimella. From Domus 47, November 1931

Melchiorre Bega, Oceanarium pavilion, National agriculture exhibition, Bologne, 1935. Photo Villani. From Domus 91, July 1935

Melchiorre Bega, Cafeteria, National agriculture exhibition, Bologne, 1935. Photo Villani. From Domus 91, July 1935

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Sacchetti, Bologne, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 136, April 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Sacchetti, Bologne, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 136, April 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Dellepiane apartment, Milan, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 137, May 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Galimberti apartment, Milan, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 137, May 1939

Melchiorre Bega, D. apartment, Milan, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 143, November 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Melchiorre Bega, Desk for Altamira, 1954. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 292, March 1954

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Renzo Durand de la Penne, Office complex, Milan, 1970. Photo Papafava. From Domus 484, March 1970

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Alberto Legnani, Giorgio Ramponi, Casa appenninica at the Triennale, 1931. Photo Crimella. From Domus 47, November 1931

Melchiorre Bega, Alberto Legnani, Giorgio Ramponi, Casa appenninica at the Triennale, 1931. Photo Crimella. From Domus 47, November 1931

Melchiorre Bega, Oceanarium pavilion, National agriculture exhibition, Bologne, 1935. Photo Villani. From Domus 91, July 1935

Melchiorre Bega, Cafeteria, National agriculture exhibition, Bologne, 1935. Photo Villani. From Domus 91, July 1935

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Sacchetti, Bologne, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 136, April 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Sacchetti, Bologne, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 136, April 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Dellepiane apartment, Milan, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 137, May 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Galimberti apartment, Milan, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 137, May 1939

Melchiorre Bega, D. apartment, Milan, 1939. Photo Villani. From Domus 143, November 1939

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Melchiorre Bega, Villa Bega, Bologne, 1941. Photo Villani. From Domus 165, September 1941

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Aldo Avati, Melchiorre Bega, Grand Hotel Duomo, Milan, 1950. Photo Villani. From Domus 250, September 1950

Melchiorre Bega, Desk for Altamira, 1954. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 292, March 1954

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Ridotto dei Cineconvegni, Milan, 1960. Photo Casali Domus. From Domus 371, October 1960

Melchiorre Bega, Renzo Durand de la Penne, Office complex, Milan, 1970. Photo Papafava. From Domus 484, March 1970

Similarly to several architects from his generation, the economic boom and the building craze of the period following World War II represent for Bega an occasion to update his language and his research axes. Even more importantly, this is the fortunate age when he can access larger scale commissions. Therefore, starting from the 1950s Bega’s activity expands from product design to interior design, for instance for the Ridotto dei Cineconvegni in Milan (1960), and to architectures of often remarkable size in Italy, such as the SIP Tower in Genoa (1967), and abroad, including the headquarters of Axel Springer publishing house in Berlin (1965).

Him fame in the postwar period, though, remain linked mostly, and for radically different reasons, to just three buildings. In Bologne he builds the Rotary House in piazza Ravegnana (1954), next to the famous towers that are the symbol of the city. A straightforwardly contemporary addition to a well-preserved historical context, his small-scale architecture causes a public uproar, to the point that it becomes an icon of the debate on historic centers preservation in Italy.

Milan’s Torre Galfa follows a more successful trajectory. The tower is completed in 1961, and it is inscribed in the larger compound of the financial center of Lombardy’s chief town, where Bega also realizes the Stipel Building (1964). Entirely clad in a sophisticated curtain wall, it is a typical international style office building which rapidly becomes, alongside the adjacent Pirelli skyscraper (1960), a symbol of the Milanese ideal of modernity of that time. Furthermore, Bega continues his collaboration with Motta, which is then expanding its distribution network along the newly-born Italian highways. The famous bridge-type service station in Cantagallo (1960) is inaugurated shortly after the very first building of this typology, completed in 1959 in Fiorenzuola d’Arda by Angelo Bianchetti, for his client Mario Pavesi. Also noteworthy is the partnership with Pier Luigi Nervi, supporting Bega for the structural design of another Motta service station in Limena, near Padua (1965-1967).

The office complex for Selezione in Milan, that he builds with Rendo Durand de la Penne at the turn of the 1970s, is one of his last large commissions. With its sculptural volumes and his fair-faced concrete elevations, it witnesses Bega’s dismissal of his modernist phase, and his approaching more brutalist-oriented aesthetics and materials.

It is precisely this ability to evolve through different ages, steadily keeping a fairly good average quality of his production, that makes Bega representative of a larger group of 20th century Italian practitioners. To conclude, while he doesn’t stand out for any substantial contribution to the theoretical reflection on the discipline, he remains close to the cores of the critical debate on architecture and the city, for instance when he directs Domus, between 1941 and 1944, leading the magazine through the intricate wartime era.