Marcel Lajos Breuer was born in Pécs, Hungary, in 1902. His career had a precocious and quick start, when he was admitted at the Bauhaus at 18, to soon become a teacher and keep his role from 1022 to 1928. Walter Gropius put him at the head of the furniture workshop, and in that context Breuer could experience the combination of arts, craftsmanship and industrial production applied to all scales — from the city to the current object — and make such approach his signature interpretation of design practice.

I am as much interested in the smallest detail as in the whole structure.

In 1926, the experimentation on the use of tubular metallic structures for chairs and tables reached his highest development in the workshop led by Breuer. The first realization, and the most iconic piece in Breuer’s production, was the B3 chair, also known as the Wassily chair, composed by an innovative and peculiar integration of fabric stripes and steel structure. The series was completed by the Cantilever chair (1928) and the Cesca chair (1928), the latter an evolution of the former combining tubular structure with wood and Vienna straw. All the models were put into production by Thonet in the late 20s; in postwar years, they were produced again by the Italian company Gavina, that was finally acquired by Knoll by the end of the 60s.

Breuer left Nazi Germany in 1936, moving to London where he worked for Isokon company, were he developed hi research on the uses of formed plywood: his Long Chair (1936) was one of the most famous expressions of this period.

View gallery

View gallery

Elisabeth (Lis) Volger (née Beyer, married with Hans Volger), on a chair by Marcel Breuer, wearing a mask by Oskar Schlemmer and dresses with fabric designed by herself. Photo Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin.

Marcel Breuer, “Cesca” chair , based on Bauhaus research principles, produced by Thonet from 1928. In Domus n. 697, September 1988

Alfred and Emil Roth with Marcel Breuer, Doldertal apartment building, Zurich, 1935. In Domus n. 737, April 1992

Marcel Breuer, Breuer House – New Canaan, Connecticut, 1947. In Domus n.233, February 1949

Marcel Breuer, Breuer House – New Canaan, Connecticut, 1947. Interior view. In Domus n.233, February 1949

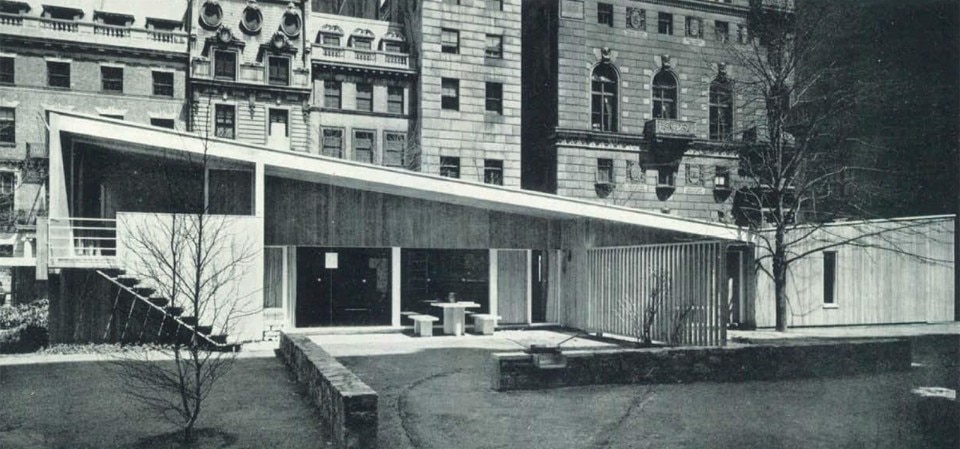

Marcel Breuer, House in the Museum garden, MoMA New York, 1949. In Domus 237, June 1949

Marcel Breuer, House in the Museum garden, MoMA New York, 1949. In Domus 237, June 1949

Marcel Breuer, House in the Museum garden, MoMA New York, 1949. Interior view. In Domus 237, June 1949

Marcel Breuer, St. John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota. View of the bell banner (1961). In Domus n.391, June 1962

Marcel Breuer, St. John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota, 1955-61. In Domus n.391, June 1962

Marcel Breuer, Bernard Zehrfuss, Pier Luigi Nervi, UNESCO Headquarters inParis under construction. In Domus n. 339, February 1958

Whitney Museum of American Art (Met Breuer), New York, 1966. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2016

Left: Lois Welzenbacher, Ehlert Holiday House, Hindelang, Allgäu, Germany, 1931-1933. Right: Marcel Breuer, Hotel Flaine, Haute—Savoye, France, 1969

Harry Seidler with Marcel Breuer, Australian Embassy, Paris, 1977. Elevations. In Domus n. 588, November 1978

Harry Seidler with Marcel Breuer, Australian Embassy, Paris, 1977. In Domus n. 588, November 1978

Elisabeth (Lis) Volger (née Beyer, married with Hans Volger), on a chair by Marcel Breuer, wearing a mask by Oskar Schlemmer and dresses with fabric designed by herself. Photo Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin.

Marcel Breuer, “Cesca” chair , based on Bauhaus research principles, produced by Thonet from 1928. In Domus n. 697, September 1988

Alfred and Emil Roth with Marcel Breuer, Doldertal apartment building, Zurich, 1935. In Domus n. 737, April 1992

Marcel Breuer, Breuer House – New Canaan, Connecticut, 1947. In Domus n.233, February 1949

Marcel Breuer, Breuer House – New Canaan, Connecticut, 1947. Interior view. In Domus n.233, February 1949

Marcel Breuer, House in the Museum garden, MoMA New York, 1949. In Domus 237, June 1949

Marcel Breuer, House in the Museum garden, MoMA New York, 1949. In Domus 237, June 1949

Marcel Breuer, House in the Museum garden, MoMA New York, 1949. Interior view. In Domus 237, June 1949

Marcel Breuer, St. John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota. View of the bell banner (1961). In Domus n.391, June 1962

Marcel Breuer, St. John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota, 1955-61. In Domus n.391, June 1962

Marcel Breuer, Bernard Zehrfuss, Pier Luigi Nervi, UNESCO Headquarters inParis under construction. In Domus n. 339, February 1958

Whitney Museum of American Art (Met Breuer), New York, 1966. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art 2016

Left: Lois Welzenbacher, Ehlert Holiday House, Hindelang, Allgäu, Germany, 1931-1933. Right: Marcel Breuer, Hotel Flaine, Haute—Savoye, France, 1969

Harry Seidler with Marcel Breuer, Australian Embassy, Paris, 1977. Elevations. In Domus n. 588, November 1978

Harry Seidler with Marcel Breuer, Australian Embassy, Paris, 1977. In Domus n. 588, November 1978

His career as a building architect developed quite more slowly, starting with punctual episodes during the 30s and the 40s, only to explode in the United States during postwar Years. Breuer was in fact involved in an interior design project for the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart in 1927, then he cooperated with Alfred and Emil Roth on the Doldertal apartment buildings in Zurich (1935) for Sigfried Giedion. The evolution of his approach to architecture witnesses the most evident features and issues of the evolution of Modern itself, starting from “a professional version (…) of some International Style principles such as the box on pillars, or the cantilevered terrace” (Curtis, 1999) in the shapes of Doldertal buildings, to shift towards a hybrid vocabulary, closer to American Modernism after World War II, to finally result in the plastic, structural expressions of brutalism.

Breuer was one of the first to understand that the mission of architects and designers is to shape current objects, drawn from current technological (and therefore social and economic) implications. (Roberto Gabetti, 1988)

The main vector for such transition was Breuer’s transfer to the United States, where he moved in 1937, initially to follow Gropius at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where the Bauhaus founder had become chairman. The two partnered in a common architectural practice until 1941, then Breuer moved to New York in 1946, where he remained based until his death in 1981. In those decades, he worked to a series of residential projects, including the participation to the Gropius house (1938) and his new house in New Canaan, Connecticut (1946), where he dealt with the first evolutions in space layout (separate day/night areas) and form that were characterizing the global diffusion of Modern reflections in postwar era. The House in the Museum garden, shown in 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art di New York, would perfectly epitomize such transition, in the structure of its roof, in the coexistence of “modern” materials with others such as stone, in the complex and dramatic relevance of the lining space, and it brought its designer in the spotlight of a higher visibility at an international level.

Starting from the 50s, Breuer worked from New York at a global scale, often cooperating with other professionals on both public and private big-scale realizations, where he experimented a brutalist approach to design, articulated in different expressions.

The modular megastructure, featuring a highly plastic and monumental formal expression, was the principle that inspired projects such as the UNESCO headquarters in Paris (1955-58, with Pier Luigi Nervi and Bernard Zehrfuss) as well as the IBM Research Center in La Gaude, Nice (1961-62). In these realizations an important role is given to the use of exposed concrete, but most of all to prefabricated concreted elements, as in the headquarters of U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (Washington D.C., 1968) or the mentioned IBM facility; by employing this technique in the project for the Flaine ski station in France (1960-70) would show his ability move across different scales , reaching the urban dimensions, and integrating them all in a unique visoon of design. Client typologies became quite diversified: private and corporate, as in the case of the Bijenkorf department store in Rotterdam (1957), or the realizations for Torin Corp. in California and Australia (1953-76) and IBM in France; public, represented by cultural institutions ( from the dormitories and the Student Center for New York University, 1961, to the Atlanta Central Public Library, 1980) and governmental or diplomatic institutions ( as in Paris from the UNESCO to the Australian Embassy, realized with Harry Seidler in 1977-78).

A sculptural approach to the use of apparent concrete was chosen for projects such as the St. John’s Abbey complex in Collegeville, Minnesota (1955-61) or the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (1966, currently the Met Breuer), this latter heavily characterized by the presence pf patterns, created through a sophisticated work on surfaces, structure and lighting elements.