Arrigo Arrighetti (Milan, 1922 - Siziano, 1989), a technician and designer employed at the offices of the Municipality of Milan, played an important role in the fertile architectural season of the post-World War II period. He was the creator of buildings and neighborhoods of great interest and was constantly committed, over the course of almost forty years of service, to promoting the creation of quality spaces with the resources then available. Not surprisingly, this civil servant was identified as early as 2012, the only Italian, by Reiner de Graaf of the OMA Studio as an exemplary case of an architect committed to the construction of society within the framework of the Biennale of Venice directed by David Chipperfield.

His first contact with the Municipality of Milan took place in 1940 when he was hired as an intern before moving in 1941, the year of his diploma at the Istituto Tecnico per Geometri, to the Divisione Edilizia Monumentale. There, after graduating in architecture from the Polytechnic of Milan (1947), he was given the task of realizing the object of his thesis. The renovation of Palazzo Sormani, heavily bombed a few years earlier was chosen as the new site with an expansion of the civic library (Domus 993, July 2015). This was his first major commission but, over the course of the eight years of its execution (1948-1956), Arrighetti worked on about thirty other projects, many of which were realized, witnessing the great trust he enjoyed within the municipal apparatus. Alongside his design commitment, he also taught as a teaching assistant in the courses of Construction Technique and Materials Technology (1947-1961), a context in which he deepened the structural possibilities offered by modern technologies and, subsequently, to the chair of Urban Planning (1961-1969), both at the Polytechnic of Milan.

.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

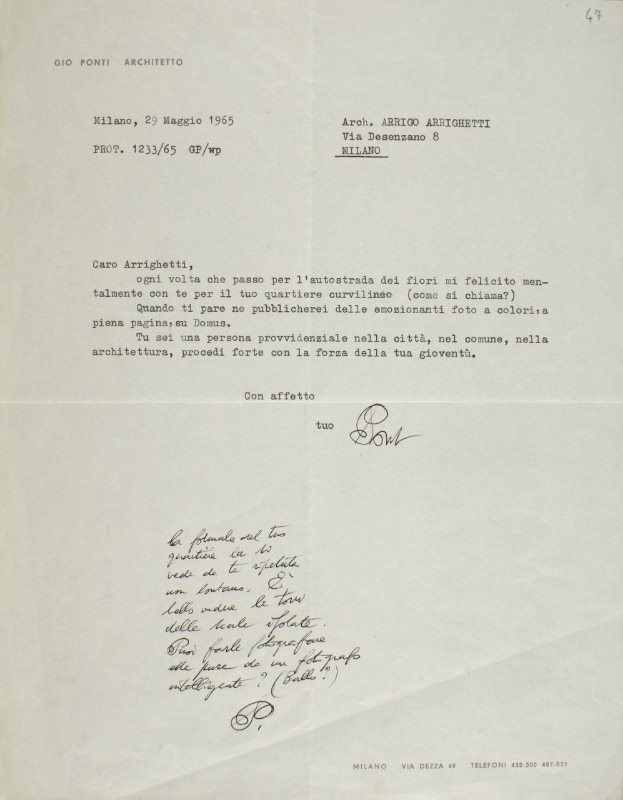

In 1956, in addition to the inauguration of the library, he was promoted to Director of the Ufficio Progetti Edilizi of the Technical Office of the Municipality. This was followed by the most intense years of his architectural production, both in terms of quantity and assortment of functional programs and building types. So much so that in 1960, a Gio Ponti involved in the editing of the guide “Milano oggi,” turned to Arrighetti to ask for his participation, his advice, and his recommendations, concluding ironically with the request of providing “somewhat lively photos, not those deserted ones that we architects make.”

In 1961, for the next nine years, he moved on to direct the Ufficio Urbanistica - which he would reorganize - also working on the revision of the Piano Regolatore Generale of 1953. Arrighetti proved to be a well-rounded architect who designed everything: both private residences, like that at QT8 for the artist Romano Rui - the only work presented in the pages of Domus in July 1954, on issie 296 - which is a revisitation of the house-workshop-studio; as well as complex housing districts, no longer thought of as satellites orbiting around the geometric, social and economic heart of Milan, but as self-sufficient organisms. An example is the Sant’Ambrogio neighborhood, upon which Gio Ponti, returning to write, asks for photos, to be taken “by an intelligent photographer”, to publish on Domus.

It is important to clarify that industrialization and prefabrication do not take away from the architect the possibility of creating freely, but rather, they open up a new field in a new technique that promises infinite and enticing possibilities.

Arrigo Arrighetti, 1955

.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

Arrighetti simultaneously builds worship buildings as well, such as the Church of San Giovanni in Bono (1968) – with its cusp-shaped exposed concrete volume that has made it an icon of Milanese brutalism – or that for the Anno Santo (1974); for sports, like the Piscina Solari (1960); for education – about twenty projects for schools dedicated to different age groups – but also architectures linked to infrastructural systems like the model subway station Amendola (1957-60). A fascination with the design exercise emerges as an opportunity for constant experimentation, followed by surprising productive efficiency and architectural quality.

Often the spatial programmes are born as a reaction to the urban context, which opens up a series of relationships and transitions between the public and private spheres: this is the full-empty relationship in school projects, both in compact structures and in more sparse areas, as in the Martin Luther King Nursery School (1951) in QT8, or in correspondence with infrastructural routes, as in the buildings in via Clericetti. Particularly important are the architectural singularities embedded in the spaces of everyday life, such as the Solari swimming pool in the Don Luigi Giussani Park or the church of San Giovanni in Bono in the neighbourhood.

The fundamental and irreplaceable function of greenery is environmental balance. This consideration applies to both proper parks and agricultural green areas surrounding the city.

Arrigo Arrighetti, 1969

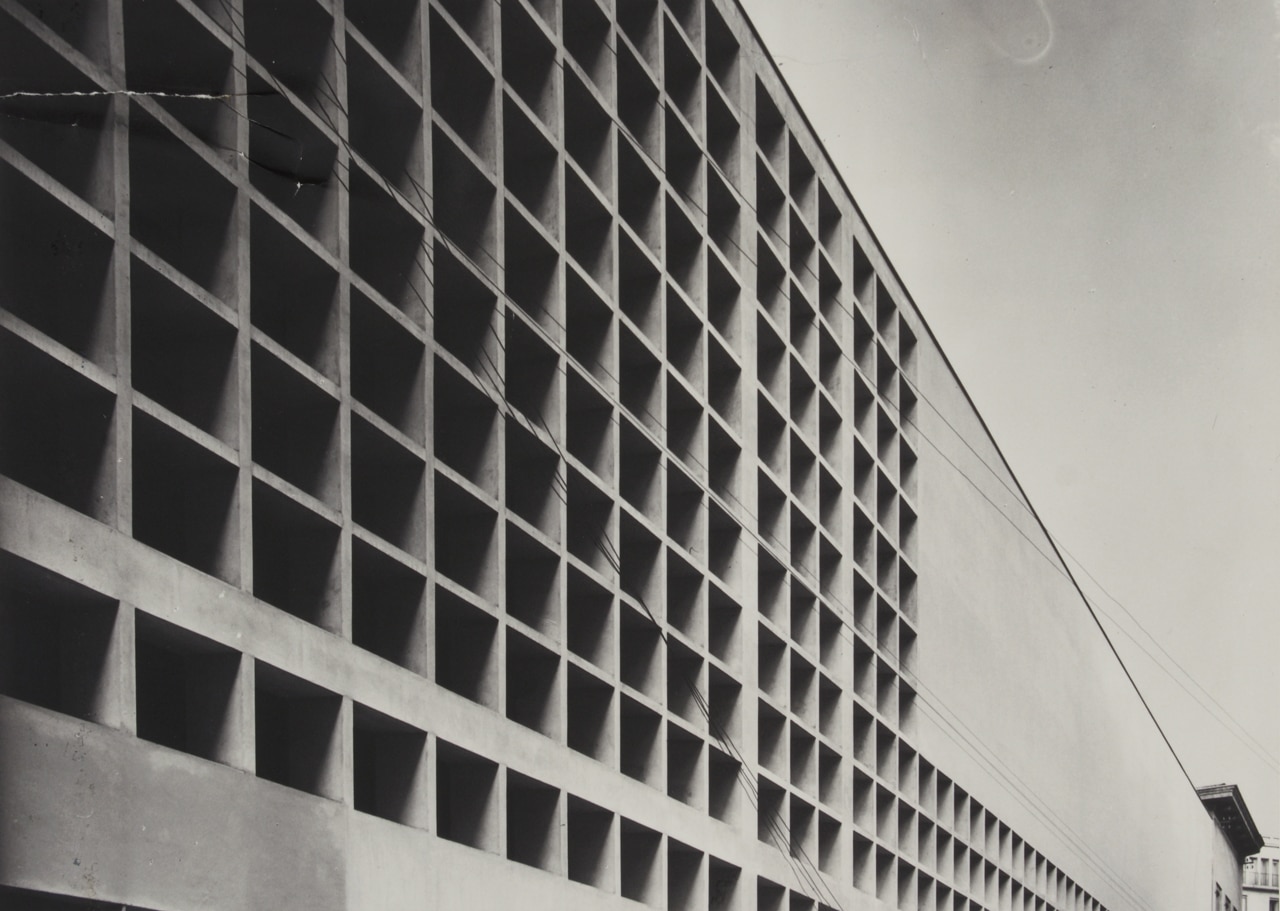

There is also a frequent return to technological and linguistic solutions, true variations on the themes that Arrighetti seems to love: the module as a compositional element both of the plan and of the façade, see Palazzo Sormani (1956); natural light, often reduced with those skylights that illuminate the innermost parts of the buildings, schools and research institutes in primis. As well as those permeable facades that become filters between the inside and the outside, either through screening operations, by means of repeated elements, or through the construction of diaphanous membranes that allow the greenery of the gardens to enter the interiors.

The lack of protocols and normative references for some specific objectives, such as the School for Amblyopic Children (1955) or the Anti-Tuberculosis Vaccine Institute (1952), favoured comparisons with specialists in the medical field, which placed Arrighetti's architecture at a pioneering level. The structure is then often an expressive element, a theme that was also refined during his courses at the Polytechnic, as Arrighetti never delegated his work solely to the expertise of engineers. In fact, his drawings show an interest in controlling the architectural organism as a whole, from the organisation of the programme to the engineering of the construction, for a substantial quality of architecture, almost indifferent to its media impact. Arrighetti also built for the same administrative apparatus in which he worked, as shown by the office buildings in Via Deledda (1956), Via Boldini (1958) and Largo Treves. In this case, the demolition of the "bidoncino", as the Milanese called the former ten-storey office building, began in 2024.

.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

From 1970 to 1976, he was the Deputy Director of the Technical Office of the Municipality and coordinator of the planning sectors, plan execution, and private construction. After becoming Co-Director for the following three years, in 1979, he left his position in the Municipality for private practice. Among the most significant projects that engaged him in the last ten years include the reorganization of the Mercati Annonari area (1980), the Centro Tecnologico in Naples (1981), the new Zona Annonaria in Pavia (1983), and the slaughter house in Perugia (1985).

With around 150 buildings realized, mainly in Milan, over a lifetime that lasted just 67 years, the numbers alone would suffice to make Arrigo Arrighetti one of the decisive architects in the Milanese panorama, if only for the dense presence of his work imprinted in the streets, gardens, and neighborhoods. But it would certainly be a partial reading, given that from the many works that we can still observe and inhabit today, the defining traits of a designer who has innovated in the field of architecture and interpreted many of the changes in post-war Milan emerge.

Opening image: Arrigo Arrighetti, Church of San Giovanni in Bono, 1968. Photo Marco Menghi