Images and words chase and bind as Dorothea Lange describes her photographs to the visitors that walk through the rooms of Palazzo della Penna, in Perugia's historic center. Indeed, the captions of the more than 130 shots faithfully reproduce passages from the notebooks of the reporter, who died in October 1965, often going far beyond the mere description of the scene:

Young mother, twenty five, says 'Next year we'll be painted and have a lawn and flowers.' Oregon. 1939

These are true and brutal episodes of life that take the veil of mystery off so to recount the ordinary tragedy that befell the United States following the Wall Street stock market crash, in an exhibition curated by Monica Poggi and Walter Guadagnini and produced by Cemera – Centro per la Fotografia di Torino.

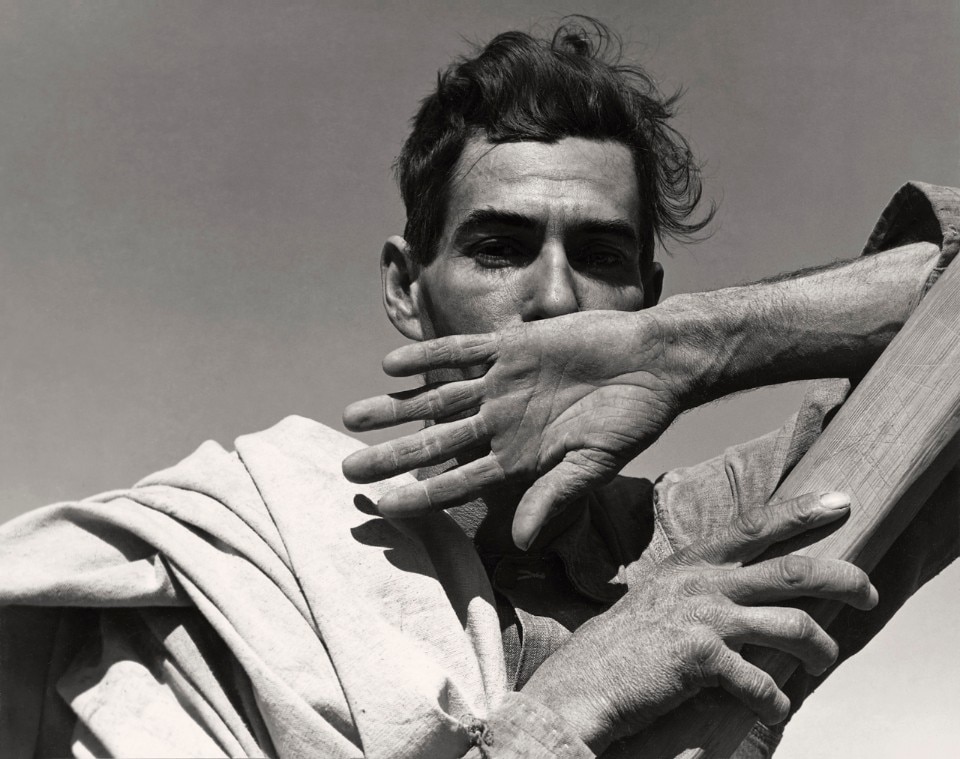

In the early 1930s, history, current events and politics prompted Lange to abandon portraiture and set out on a journey toward an authentic understanding of what moved people in those unfortunate years, through an objective but never impersonal eye.

The only woman along with Marion Post Wolcott, she is called upon by the Farm Security Administration, a government program created to promote New Deal policies to support the country. She is thus sent to document the disastrous living conditions of farmers forced to migrate because of the fierce drought that hit parts of Central America between 1931 and 1939.

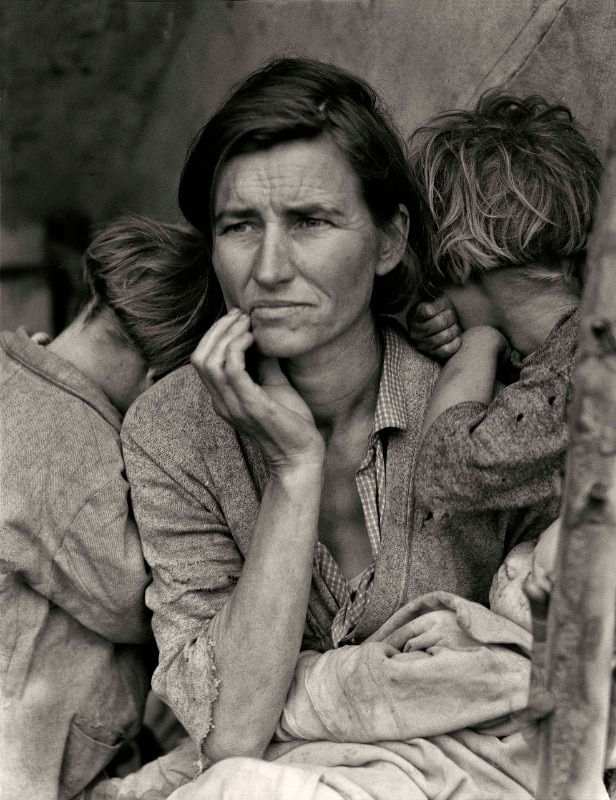

The Dust Bowls, the violent rains of sand that destroyed crops, are the background of the broken lives of men, women and children, “fleeing poverty headed for another poverty” (W. Guadagnini).

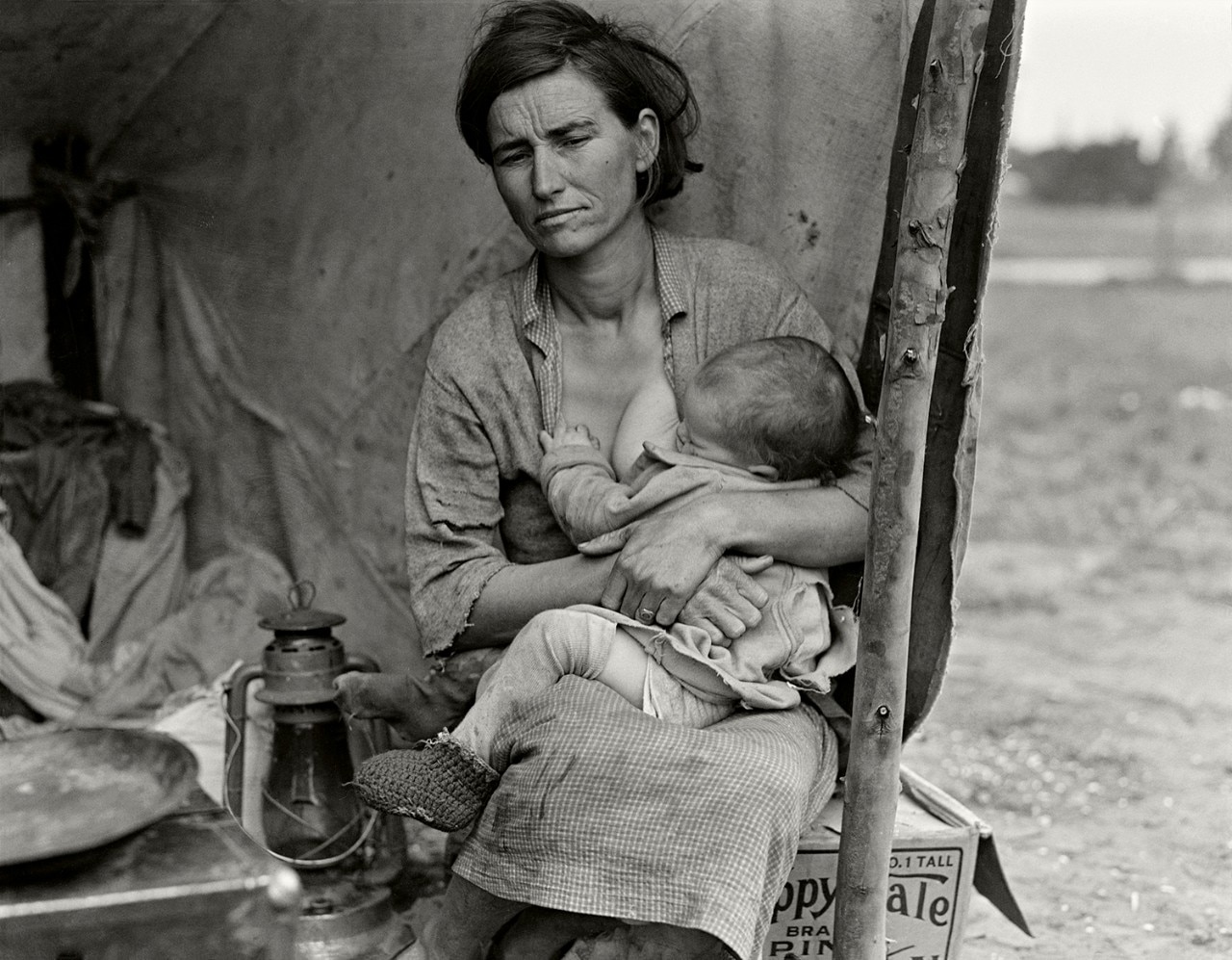

Grandparents and grandchildren looking out of the small windows of unstable shacks, very young mothers with newborn babies close to their chests, children with hard eyes, sick and with no strength.

Of the women, the most frequent subjects within this first cycle, Lange often notes their age, testifying to a sometimes acerbic, aggressive, unnatural motherhood.

Florence Owens Thompson, the face of her most famous shot, The Migrant Mother, is thirty-two years old and has seven children: “She sat in that little house tent, with her children crowded around her, and she seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me” (Dorothea Lange, Popular Photography February 1960). She made a series of five shots — a silent, almost sacred dialogue with a modern Madonna and Child and a face that exudes despair.

In 1942, Lange was again called upon by the government with a new assignment: to document the deportation of American citizens of Japanese origins, all considered potential spies following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Thousands of people are forced to abandon their homes and jobs and sent to detention camps set up in semi-desert areas. Lange publicly expresses her disapproval of the operation, thus being denied the opportunity to keep the negatives of her images. She accepts the assignment because she is convinced that her work may one day expose the brutality and violence perpetrated by the U.S. government. This will happen, much belatedly, only in 2006 with the publication of the book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment by Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro.

From forced business closures to the long lines waiting for registration, from boarding buses and trains to ordinary life in the camps. Lange follows the exodus of about 110,000 people attesting to their dignity, to the serenity of being on the right side of history.

Her priceless work was celebrated in 1966 with an exhibition at MoMA, the first retrospective the museum devoted to a woman photographer. Dorothea Lange died a few months earlier of esophageal cancer, spending her last time choosing the images to exhibit. The ultimate proof of her total and stubborn dedication.