“I was tired of the audience doing nothing,” Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley tells me when I ask the obvious question: why video games, rather than painting or sculpture? We’re sitting on reclining theater chairs in a room repurposed as an office, near their Berlin exhibition at the Halle am Berghain, the art space at the rear of the world’s most famous club.

The occasion is the opening of the second episode of their solo exhibition, The Soul Station, which first launched in the summer, commissioned by the Las Art Foundation. Joining us is Las curator Boris Magrini, who highlights the foundation’s mission of merging art, science, and technology. Magrini sees Berghain as the perfect venue to showcase Brathwaite-Shirley’s work – just like the club itself, it’s a space that’s recreational, countercultural, and uses “popular culture to subvert established mechanics and develop critical, experimental approaches.”

“Archive” and “honesty” are the two words that surface repeatedly during our conversation with Brathwaite-Shirley, a retrofuturist artist who could be described, using a throwback to the ’70s, as “militant” – with a nod to “political games.” Their video games and interactive experiences reflect encounters with marginalized groups – particularly Black, queer, and trans communities – that society often overlooks. Each project begins differently, they say, “but it usually starts with a conversation or workshop with a group of people I want to work with.”

The games function as an archive of those conversations – “an untraditional way of archiving,” they explain, likening it to the imaginative world-building of science fiction. “You understand the general themes, but it’s not necessarily your reality.” This approach, the artist argues, avoids the worst pitfalls of traditional archival work, particularly its tendency toward pornification. History is full of examples of trans people whose only records are arrest documents and official files, they note. What’s missing are “the poems they wrote, the stories they told, or a picture of their face on a normal day.” Brathwaite-Shirley brings up Mary Jones, a 19th-century trans woman from New York labeled a “man-monster” by the press, whose arrest record is all that remains of her life. “But she was a genius. She even made herself an artificial vagina”. And yet, they add, “I’m probably repeating my own mistakes.” But they hopes imperfect archives are at least “a little more honest, trying to collect the soul and show the soul.”

The concept of the soul is central to the exhibition. A large sign greets visitors just outside the entrance to Halle, echoing the theme: “Everything you’ve ever done / is recorded in your soul” and “You may not be able to bear the truth / but it’s not too late / to change.” The final line, “take a look,” could just as easily have said, “play it.” For Brathwaite-Shirley, “video games offer a unique way to challenge yourself,” to engage with deeper truths. The overarching idea of the exhibition, if it could be distilled, is that a video game might not change your soul, but it can help you understand something new. It’s a manifesto for political and moral video games.

“One of the best moments is when players don’t know what to do with a choice, and they freeze – while the game just goes on,” Brathwaite-Shirley says. This paralysis, when an emotion is caught inside the soul, is exactly the state they want to induce. It’s also what they enjoy witnessing when they watches people play. In his art, play is the act of playing: the video game and its setup, its play station, are conceived together by Brathwaite-Shirley, they are inextricably linked, ‘like two children who are born separately, but then grow up to be one’.

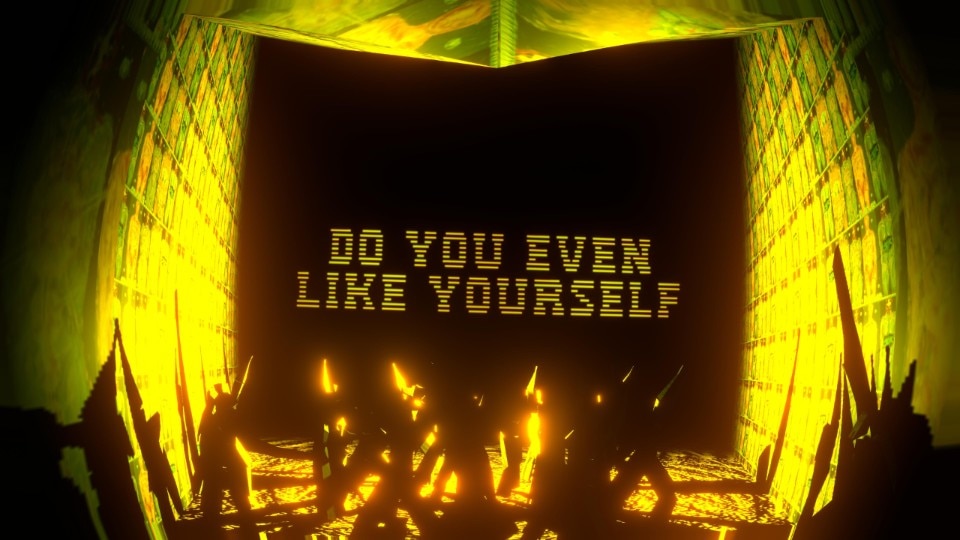

The exhibition space for The Soul Station is a retrofuturistic arcade, housed in the post-industrial halls of the Halle. Its worn walls and towering columns are transformed by the glow of Brathwaite-Shirley’s video games, whose visuals seem to spring from the subconscious of the golden age of gaming. Their games confront the glossy perfection of today’s Instagram-filtered world with a radical, unapologetically rough aesthetic. It’s a stark contrast to the mainstream video game industry, which exhausts its workers to produce perfectly polished games. “Why take the risk of making a political game when you can make billions just by making people shoot stuff?” the artist comments, making an explicit criticism of the fact that in many video games the only point of satisfaction is to accumulate corpses of enemies. .

One of the best moments is when players don’t know what to do with a choice, and they freeze – while the game just goes on

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

When I ask Brathwaite-Shirley about their references, they passionately tell me about their research in the world of video games and how they find inspiration in forgotten titles from the last century. The conversation moves from the hacker contribution in the Amiga years, the 1980s, when games still ran on floppies, to the game engines they have tried in recent years; from Muriel Tramis’ 1987 game Méwilo, one of the first video games to address slavery and colonialism, which unsurprisingly wasn’t well-received in France. They also mention Forbidden Siren (Japan Studio, 2003), Echo Night Beyond (2004, FromSoftware), and the Disaster Report series. They found Raw Danger!, the sequel to the original Disaster Report, particularly moving. “It shows things as they really are,” they say. “It’s horrible – you’re just trying to survive a tsunami, everyone’s devastated. It’s a deeply depressing atmosphere.”

Brathwaite-Shirley’s works are tied together by a common thread, creating a somewhat coherent universe with its own internal chronology. Hence, the concept of a “second episode,” which updates all of the “Death Station” games previously shown in the exhibition, adding four new titles to complement earlier works like Pirating Blackness and Invasion Pride. A new chapter has also been added to the central arena game, the exhibition’s centerpiece, which towers over the Halle. In this game, a single player sits in a reclining station while other spectators can become either helpful allies or formidable opponents.

The exhibition space for The Soul Station is like a futuristic arcade, housed in the post-industrial halls of the Halle. Its worn walls and towering columns are transformed by the glow of Brathwaite-Shirley’s video games, whose visuals seem to spring from the subconscious of the golden age of gaming

The interaction happens through tablets, where players are confronted with what Brathwaite-Shirley calls “really unpleasant questions” like: “Are you complicit in your government’s actions?” or “Do you support immigration?” or even, “Is it okay to be a failure?” The answers affect the player’s remaining time, displayed on a timer visible on the large circular screen where the game unfolds.

This second episode, Are You Soulless Too? (the first was titled You Can’t Hide Anything), differs from its predecessor. Instead of using a text written entirely by the artist, it’s based on conversations with five Black and queer people. The game tells the story of two groups who meet, believing they have something in common, only for one to demand that the other change and abandon their identity. Themes of the body, fear, immigration, marginalization, and the pain of not being accepted are woven throughout. Despite the playful appearance of digital creatures and colorful illustrations, the game packs a visceral, political, and existential punch. It leaves a lingering sense of danger and unease, long after you’ve finished playing.

- Exhibition:

- The Soul Station

- Location:

- Halle am Berghain, Berlin, Germany

- Dates:

- from 12th July until 13th October 2024