During your average away game of the English football national team, chances are that you’ll see adults dressed up at St. George’s, singing World War II songs while downing European lagers and wearing clothes made in Far East sweatshops, all of this by jumping into the fountains of historical squares. Corbin Shaw offers snapshots of this Britain caught between the old-fashioned world of the Empire that once was and the uncertainties of a nation in search of an identity in the aftermath of Brexit. He does so by clinging to vernacular simulacra, from folklore traditions to the oversized mugs of sportswear chain stores, but never accuse him of romanticising nostalgia.

Nostalgia, dismay and… Paul Gascoigne: the post-Brexit art of Corbin Shaw

Domus meets the British artist who reflects on what it means to live in the UK today, a country loving its tradition “despite people struggling to heat their houses”. His new solo exhibition is in Milan.

View Article details

- Lorenzo Ottone

- 08 November 2024

“My relationship to Britain is a complicated one. It's a kind of love and hate,” explains Shaw reflecting on the conflictual nature of living in a country that “loves to keep up its traditions despite people struggling to heat their houses”. It could be argued that Shaw is one of the leading figures of Post-Brexit art, not a codified scene, rather an aesthetic taste and a feeling common to the generation of artists and creatives born on the cusp of the third millennium and saw their future scrapped by the life-changing referendum while coming of age.

Irreverent and playful in the form, Shaw nonetheless demonstrates a strong political conscience in researching the roots of the iconographic myths of the United Kingdom, at home and even more so abroad. A consciousness that also emerges in his will to create economically accessible multiples and works, to democratise art.

The artist – born in 1998 in Sheffield, the steel city of the great industrial British North that once was – engages with the study and critique of a country that has radically changed, yet still finds solace in its little big iconographic certainties and bastions, whether old or shockingly new. Shaw questions them all, “to find a sense of home in it all, and try to deflate England’s ego”.

I don’t really find comfort in a lot of the old stuff because it’s so distant and it’s so alien: my comfort and culture is supermarkets and things like that.

Corbin Shaw

Up North, his North, Amazon and DHL warehouses have colonised the fields and the factories of the tea-sipping working-class, whereas in London vape shops and coffee multinationals have occupied the Georgian buildings which once housed cafs and greasy spoons, with their black-and-white chequered floors and glossy tiled walls. “Where has craft gone?,” wonders Shaw, finding in the theories of William Morris and Ruskin an inspiration in reflecting on the industrialisation of the landscape and the apocalyptic fastness of today’s world, from food to fashion. “Where are those trades and where are those techniques that tell people stories about the civilisations that lived there? Maybe to tell the story of what Britain was in 2024 they’ll have McDonald’s toys fossils.”

The childhood memories, grasping in pubs and at the football the last exhales of a somehow authentic Britain in the late 1990s and 2000s, clash and amalgamate with the grittiness of everyday life. “I think A lot of the places that I grew up in or spent time with my family were new buildings, housing estates and retail parks. So, I don't really find comfort in a lot of the old stuff because it's so distant and it's so alien: my comfort and culture is supermarkets and things like that.”

His nostalgia never bursts into conservative feelings, but into abrasive post-hirony, which hits straight at the heart of those who grew up on the rubble of Her Majesty’s empire. Similarly to the social commentary The Kinks offered, at the dusk of the Swinging London, in Arthur or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire. The King Arthur souvenir mug that adorns the album cover strikes resemblances with Shaw’s ceramics emblazoned with the logo of Stella Artois, which has fully replaced English ales and bitters in pubs. Or, to quote the more recent Slowthai, naked on the block in the courtyard of a council estate, Nothing Great About Britain.

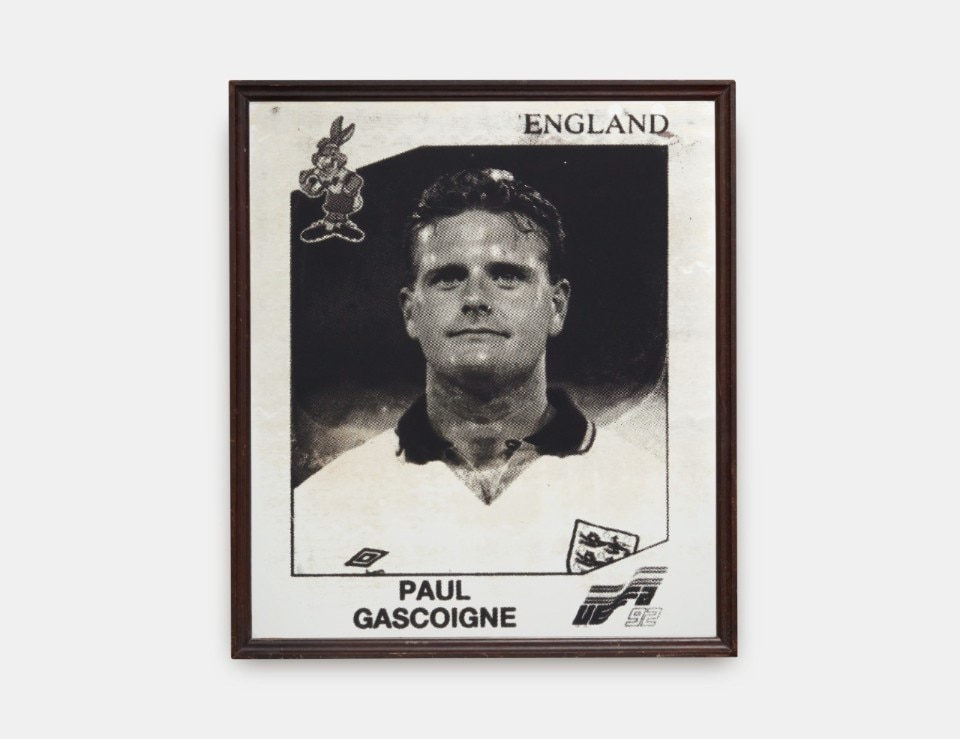

The St.George’s flag carried by English football fans on their away days is hence turned into a platform for humorous or social messages; the ancient art of tapestry – a cornerstone of British identity since 1066 – is reappropriated to portray shopping centres; Paul Gascoigne, scratch cards and the pages of tabloid newspapers in the hands of Shaw become pop icons, like Marylin and Elvis to Warhol. The pagan dance of Maypole is elevated to element of cultural critique and performative art; found automobile crests are repurposed into wrestling belts for Tesco car park scuffs; patches and badges – forgotten pieces of merchandise – help narrating a generation which doesn’t want to lose its identity, yet that is determined to find (and write) its own iconoclastic place in the country.

The grittiness and questionable beauty of everyday life is elevated into poetics because, after all, it's part of us and we can’t help but fall in love with it all, just like the average and vernacular Italy portrayed by Guido Gozzano in his writings. Shaw seems to strike a balance, between karaoke pub songs and raves, which deflagrates into Eurotrash, the artist’s own manifesto. A term which in the aftermath of Brexit acquires an even more compelling semiotic stance.

“It’s unserious music that I take really seriously, in the style of Eurodance. It is a slur which came out mourning the being out of the EU and thinking about the state of Britain, of us being a sort of Eurotrash. British people would say ‘rubbish’, not ‘trash’, so I love the quirkiness of it and how it feels, because I think that a lot of British culture is now becoming so Americanised.”

A cultural hyperbole that, as Shaw points out, has led to seeing Trump flags during English nationalist rallies. “Only 20 years ago if you spoke to one of those nationalists, they would have never, ever assimilated with anything American.”

Eurotrash is also the title of the solo exhibition, the first in Italy, that Shaw is bringing to Milan on November 8-11 at Spazio Maiocchi powered by Slam Jam. “An immersive portrait of a nation caught between fading grandeur and a fraying sense of belonging; confronting both the historical British landscape and its contemporary political divides.”

- Eurotrash

- Spazio Maiocchi, Milan

- from 8 to 11 November