Rome, April 26th, 121 AD. Marcus Aurelius was born. He was a man destined to thread the paths of history as both emperor and philosopher. Since his youth he had been interested in philosophy, finding in the teachings of the Stoics a balm for the spirit and a compass for life. Fate led him to the throne in 161 AD., handing him the reins of the Roman Empire.

Holding the reins of the power, Marcus Aurelius did not transform into a tyrant surrounded by luxury and opulence. On the contrary, he remained an austere man, plagued by doubts and the challenges his role entailed. Wars on the borders, pestilences claiming lives, and internal insurrections – his reign was a succession of trials that tested his spirit.

The emperor found solace in philosophy, drawing strength and wisdom from it. In his Meditations, mostly written amidst the tents of military camps, he poured out his most intimate thoughts, fears, and reflections on the ephemeral nature of life: “Do not seek to have events happen as you want them to, but instead want them to happen as they do happen, and your life will go well.”

As a powerful symbol of imperial power, Marcus Aurelius is portrayed not only as a military leader but also a philosopher and a sage.

He proved to be a just and far-sighted emperor, attentive to the well-being of his subjects. He promoted education, culture, and religious tolerance, guiding the Empire with a firm yet compassionate hand.

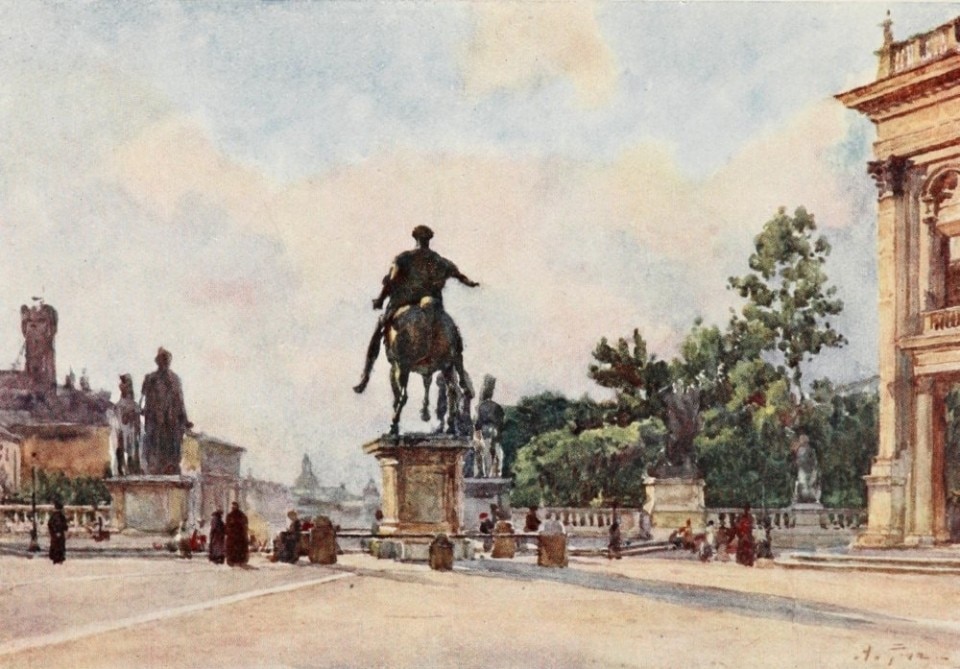

His reign came to an end in 180 AD., when death caught him at the age of 58. In the heart of Rome, in the Capitoline Hill, a bronze knight reigns supreme, an eternal symbol of ancient Roman power – the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius.

Its original location is shrouded in mystery. It was probably placed in the Roman Forum or near the dynastic temple of the Antonine Column. However, in the Middle Ages, the statue was moved to the Lateran, where it risked destruction due to misidentification. Saved by chance, in 1538 Pope Paul III brought it to the Capitoline Hill, destined to become the centerpiece of the square designed by Michelangelo.

Created between 176 and 180 AD., the sculpture depicts the philosopher emperor in all his majesty, on horseback, leading his people to victory.

Nearly 4 meters high, the statue captures the essence of Marcus Aurelius with remarkable precision. The emperor is depicted with a solemn and thoughtful expression, reflecting his wisdom and sense of duty. The masterfully crafted body conveys strength and composure, while the elegantly draped toga reveals his high rank. The horse, also crafted with great realism, seems to advance with a firm step, emphasizing the power and determination of its rider.

As a powerful symbol of imperial power, Marcus Aurelius is portrayed not only as a military leader but also a philosopher and a sage. His calm expression and thoughtful attitude embody the ideals of the beloved Stoic philosophy.

Eugène Delacroix, master of French Romanticism, immortalized the emperor in a dramatic moment, a painting of poignant beauty – Last Words of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

In the twilight shadows of the room, Emperor Marcus Aurelius, exhausted and marked by illness, utters his last words, a final whisper of wisdom that echoes within the walls of his immense power.

In the middle of the canvas, Marcus Aurelius sits on his deathbed, wrapped in sheets. His body is already weakened, and it is painted in shades of gray and purple. His left hand, marked by time and fatigue, rests on the arm of his son Commodus, a young man of slender and proud figure, dressed in sumptuous Eastern garments.

The death of Marcus Aurelius, symbol of power and wisdom, in the face of his son’s indifference and the uncertainty of the future, becomes a metaphor for the transience of all earthly things and the solitude that accompanies man in the face of his destiny.

Commodus, heir to the throne, watches the scene impassively. His gaze, devoid of compassion, seems directed elsewhere, towards the viewer, towards the future that awaits him as emperor. His features, devoid of a beard and adorned with earrings and a crown, betray an ambitious and ruthless nature, far from the Stoic ideals of his father.

Around the imperial bed are gathered friends and dignitaries, their faces streaked with tears and marked by grief. Among them, the figure of a philosopher stands out, perhaps Marcus Aurelius’ mentor, who with a solemn gesture seems to want to collect his emperor’s last words and pass them down to history.

The dim, golden light illuminates the scene with a melancholic aura, underscoring the fragility of life and the inevitability of death. The room, devoid of superfluous ornaments, takes on a solemn and hieratic atmosphere, as if to elevate this earthly moment to an epic dimension.

Delacroix, with his pictorial mastery, did not merely depict a historical event but captured the essence of human drama. The death of Marcus Aurelius, symbol of power and wisdom, in the face of his son’s indifference and the uncertainty of the future, becomes a metaphor for the transience of all earthly things and the solitude that accompanies man in the face of his destiny.

“If you apply yourself to the task before you, following the right reason seriously, vigorously, calmly, without allowing anything else to distract you, but keeping your divine part pure, as if you might be bound to give it back immediately; if you hold this, expecting nothing, fearing nothing, but satisfied with your present activities according to nature, and with heroic truth in every word and sound which you utter, you will live happily. And there is no man who is able to prevent this.”