Indian artist Reena Kallat’s work renders visible the urban and social fabric as a mosaic of names and lives: sometimes removed from India’s history, records and official image; sometimes even from the collective awareness, but still a strong presence, a magmatic force subtending the reality of all places at all times. In her works, Kallat lends form to the weave of countless stories that lie behind the city and she does so using a symbolic object — the rubber stamp, the main tool of bureaucracy.

She has created painted portraits on paper with the names of people denied visas because of their class, nationality or religion. Facial contours are formed with rubber stamps naming people officially registered as disappeared. Other works depict monuments in Delhi and, again, the images look segmented, as if pixelated. These feature the names of sites placed under the protection of the Indian archaeological heritage service, but gobbled up by urban growth and speculative building.

Urban Cobweb

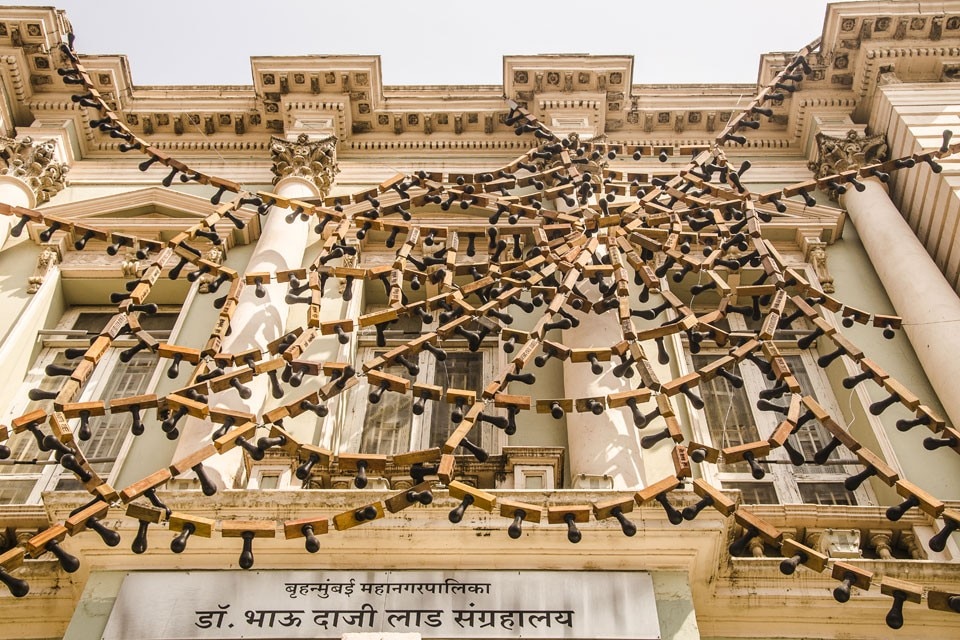

Reena Kallat’s latest work, commissioned by the Zegna Group, is an urban installation of monumental proportions — a huge cobweb spread across the façade of Mumbai's oldest museum.

View Article details

- Gabi Scardi

- 30 April 2013

- Mumbai

Originally from New Delhi, Kallat lives in Mumbai. With 20 million inhabitants, Mumbai is India’s most densely populated city and one of the most densely populated in the whole world: a megalopolis where progress and backwardness, wealth and poverty are squeezed together and live in each other’s pockets. Here, every metre of the ground is rendered useful: either paved in asphalt, or serving as somebody’s home, occupied by beds, shelters, makeshift living spaces and tiny and immense shantytowns.

Mumbai is also a rich city that runs on tireless stamina. The chaotic megalopolis has grown up over the old city forged by the colonisation — first Portuguese, then British — of a marshy area that became a precious port and was turned into a dynamic manufacturing zone, drawing massive immigration and an influx of different ethnic groups, religions and cultures from all over India and the neighbouring countries. With the growth of this ambitious, dramatic and hugely paradoxical city came the development of a complex bureaucracy that was expected to regulate, order and settle, but that is one of the most problematic in Asia.

Reena Kallat’s latest work, Untitled (Cobweb / Crossings) is an installation for “urban” application and of monumental proportions. It evokes a map, or a huge cobweb, and it is spread across the façade of the city’s oldest museum, the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad City Museum, founded in 1855 as a “branch” of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. The large-scale structure is composed of 550 large rubber stamps, oversized resin copies of those used in the past to impress street names on the city’s buildings. The stamps bear the colonial street names from the time when Mumbai was known as Bombay. Today, these names have been replaced with others of Indian origin, new or revived from the pre-colonial past. The installation narrates the stratification of time, history and memories — the weave of relations permeating the city. The use of rubber stamps also conveys the concepts of citizenship and identity, and showcases the country’s overgrown bureaucratic system. Kallat adds that the museum stands beside the former zoo, a place with cages and aviaries that retains never-waning charm. It was this proximity that inspired an organic form for the installation, resembling an animal, but also the pulsating and constantly mutating city.

To those interested in urban dynamics and “public” projects, Kallat’s work offers much food for thought — does art make sense in such a mobile and contradictory place as Mumbai? Is there space for an art project in an urban fabric that is dense to the point of saturation?

Ultimately, urban fabric is commonly and fundamentally considered public space, and as such it can be lived, used and regulated. Where does the limit lie between public and private, interior and exterior, order and disorder, organisation and entropy? What becomes the meaning of public space when its definition broadens? To what degree can its physical appearance and use be designed? Who should or can do it, and how?

The project is integrated in the ZegnArt Public initiative, conceived and promoted by the Zegna Group and curated by Cecilia Canziani and Simone Menegoi with ZegnArt coordinator Andrea Zegna. As the name implies, Public consists of three public projects — by an Indian, a Turkish and a Brazilian artist in their own countries. The three installations are produced in collaboration with a local institution in the host country and will be donated to that same institution. Kallat’s work will thus remain at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad City Museum in Mumbai. In an effort to encourage the creation of new relationships, the initiative also includes the offer of a residency at Rome’s MACRO to a young artist from each of the three countries. Gabi Scardi