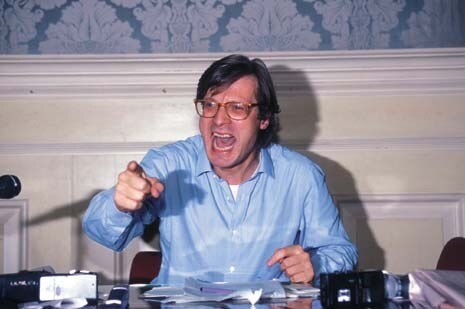

One particularly memorable description of Sgarbi’s brief tenure as a junior culture minister in Silvio Berlusconi’s government was that ‘he played the role as if he were engaged in a Dadaist performance work’. He will be remembered for sharing with an American journalist his sincere wish that the president of the Venice Biennale – whom his ministry had just appointed – could, as far as he was concerned, ‘go and drown in the lagoon’. He vowed to complete the La Fenice opera house and pontificated about the Taliban’s destruction of the monumental Buddhas of Afghanistan. But his real ambition was to cast himself as Italy’s answer to Britain’s Prince Charles. Like him Sgarbi posed as an arbiter of architectural taste. And like the prince he was petulant and arbitrary in his enthusiasms and anathemas.

The opportunities to play on Vittorio Sgarbi’s surname (‘bad manners’ in Italian) provided endless opportunities to make feeble puns. Few, though, have yet resorted to irony about his first name, which he shares with Vittorio Gregotti. The latter, despite the open war declared on him by Sgarbi with the famous last words ‘As long as I am Undersecretary for Culture he won’t be building anything else in Italy’, sailed, unscathed, above the invective, calmly building theatres and homes, offices and banks. Sgarbi, on the other hand, has to flutter from one pole to another – especially now that the political Polo alliance has dumped him. This was due more to his continuous attacks on his own minister than his lukewarm opposition to one of the numerous bills to ‘market’ the nation’s heritage (art treasures included) that are regularly submitted to the Italian Parliament.

Tepid though it was, that opposition has won him the unlikely approval of a number of progressive notables with short memories. Oddly ready for once to jump onto the losing bandwagon, they have tried to take advantage of Sgarbi’s abrupt dismissal to lure him back to the left. Nothing could be farther from the brilliant and specific ‘Sgarbi syndrome’, a malady whose symptoms include absenteeism, an allergy to any fixed post, insomnia and a mania for flying everywhere at the state’s expense. This is not to mention a sort of D’Annunzian anarchy whereby all is delegated to contradiction, and at the same time a perseverance with fixed ideas, like an excitable Don Quixote or Robin Hood. Sgarbi harboured an enthusiasm for two architects who could hardly be less compatible, Massimiliano Fuksas and Mario Botta, and he foisted the latter onto La Scala for a piece of completely unnecessary and intrusive shape-making on its roof. But he had a much longer and equally ill-assorted architectural blacklist. He picked very public fights with Richard Meier, Arata Isozaki, Giancarlo De Carlo, Alvaro Siza, Alessandro Mendini and others.

He tried to wipe them all off the face of Italy’s cities for ‘crimes against antiquity’: Mendini for having dared to transform a bit of old scrap iron like the gate of the Villa Reale in Naples into a dignified urban symbol. Meier for having attempted to make the Ara Pacis legible and accessible to visitors by means of a new pavilion instead of the old fascist one. Isozaki for having legitimately won a competition promoted by the Italian State for a new exit to the Uffizi Museum. De Carlo for having envisaged a new steel and glass roof (some novelty!) on an ancient building. Siza for a deft, sensitive proposal to display a Michelangelo sculpture. And so on and so deliriously forth, until decades of serious debate about the relationship between the past and present was reduced to idle bar talk. Diderot was quite right: ‘Blessed were the ancients, for they had no antiquities’. And, it might be added, they had no Sgarbi either. On the vague pretext of preserving the values of our artistic tradition, he managed to collect – first as a private television entertainer and later as Undersecretary – enough gaffes to fill a whole cycle of Italian comedy films.

And yet this folkloric figure, now that he has lost the gilt of illustrious defeat, can even inspire a certain compassion, a readiness to grant the honours of war to a name that is no longer a presage but, if anything, an intriguing oxymoron for the main character in an instructive nursery rhyme on mechanisms of communication that may be a pleasure to pass down to incredulous children. About our budding Frankenstein’s monster, the media system can at last sit back and say: ‘I created you, now let me destroy you’.