1967, the Canadian Centennial: a new country only one hundred years old, stepping into the future, the feeling that everything is possible. A bipartisan extravaganza in which the leadership of conservative and liberal parties of the time join in immensely successful celebration marked by an air of optimism, and more specifically the prominence of an emerging multicultural vision of the nation, including the foregrounding of First Nations. In Montreal, Expo 67 was the sight and showcase of some of the most utopian and radical visions for architectural projects, in response to the theme of “Man and His World” which central question was how to live together: Moshe Safdie’s Habitat or Buckminster Fuller’s Biosphere became the images of the decade. In Ottawa, the nation’s capital, the National Art Center is designed by Fred Lebensold. At this time, benefiting from federal funding in the lead up to the confederation’s centennial, Toronto begins to emerge as a modernist capital: Toronto City Hall by Viljo Revell is inaugurated in 1964, the same year, Scarborough College and the Science Center are completed by John Andrews and Moriyama Teshima Architects respectively, while Ludwig Mies van der Rohe completes the TD Center in 1969.

One of the Canadian centennial’s major projects, which still upholds its iconic status as emblem of the utopian values of young Canada is Ontario Place. On the shore of Lake Ontario, the island, the result of the collaborative work of Canadian landscape architect Michael Hough, and the architect Eberhard Zeidler, became as a piece of infrastructure, what was perhaps the most potent symbol of social equity. The futuristic landscape crystallized a microcosm of a new vision of urbanity: the integration of multiple programs including an amusement park designed for children, exhibition and educational galleries in suspended pods over water, the first permanent IMAX cinesphere and a waterfront accessible to all. At the core of the vision for this park—characterized by its winding paths, dense forests, quiet canals and navigable lagoons—was the notion that approaches to the larger landscape, “nature”, have root in cities and urbanity. And most importantly, that architecture’s purpose could be to densify the relationship with landscape and increase the coexistence between nature and cities.

But since 2019, the Ontario provincial government has engaged in redevelopment plans for the park and announced its demolition to build a private mega-spa. This sparked mobilization of the Toronto design community, and the World Monuments Fund included it in its official Watch List program in 2020, elevating the monument to the international canon of late modernist heritage, first brought to the fore in Reyner Banham seminal 1976 book Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past. In November 2024, a conference organized by Dean Robert Levit and Associate professor Aziza Chaouni at the University of Toronto John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design entitled Preservation? Modernist Heritage and Modern Toronto inscribed itself in what has been a four-year fight to preserve Ontario Place. The conference highlighted the incredible contribution of the organizations and activist groups such as Save the Science Center, Ontario Place for All, Toronto Society or Architects and the Cultural Landscape Foundation in advocating for the preservation of Ontario Place and the Science Center. The work of these groups led to the creation of important archives of knowledge on these buildings and most importantly on the need to mobilize public debate and motivation to maintain public assets in the fastest growing city in North America.

While the conference proposed to grapple with the question of the compatibility of preservation with development in the city of Toronto, its reach and significance goes way beyond. Indeed, the conference brought to the foreground a question of global relevance, that is: why is it so difficult to preserve modernist architecture today? Indeed, we so easily accept the need for preservation of monuments like the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, yet have difficulty safeguarding some of the most significant modernist monuments of the last century. The Metabolist emblem of the Nagakin Capsule Tower designed Kisho Kurukawa (built 1972, torn down 2022), The Chicago Prentice Women’s Hospital designed by Bertrand Goldberg (built 1975, demolished, 2015), the Robin Hood Gardens social housing project by Alison and Peter Smithson in London (completed in 1972, demolished in 2017) are but a few examples of architectures encapsulating the utopian visions of the recent past and which demolition point to the unease with which we are cohabitating with modernist icons today.

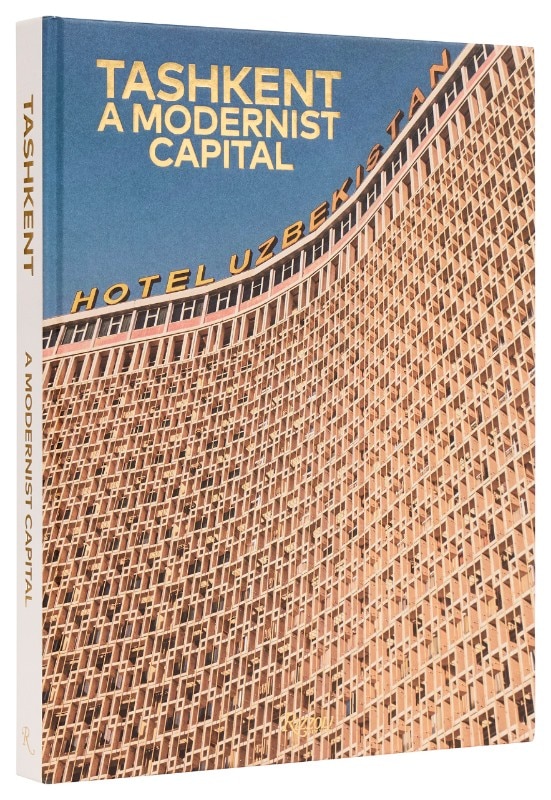

A research project under way in Tashkent, Uzbekistan—Tashkent. Modernism XX/XXI—is an example which gives hope to the possibility of reinvigorating the ideals that the modern project upheld through architectural preservation and vulgarisation efforts, energized by the participation of cultural institutions. Recognizing the gradual disappearance of the architectures built during the first phase of modernization of the city of Tashkent in the 1960s, the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) launched an extensive campaign to increase awareness of the historical significance of its modernist heritage and prevent the destruction of significant budlings. A conference entitled Where in the World is Tashkent? organized by ACDF and coordinated by Grace in 2023 led to two publications Tashkent A Modernist Capital (Rizzoli), which aims to make the architecture of the city known to a wide audience internationally, and the forthcoming Tashkent Modernism (Lars Muller), a comprehensive record of the research project. Together, the publications stand to inscribe the radical soviet social experiment which the architecture of Tashkent was a testament to as a milestone in the global map of twentieth century architectural modernism.

Perhaps it is because after the death of Islam Karimov in 2016, who had ruled Uzbekistan since 1991 the country sought to identify a clear break from its past and preserving the architecture deemed belonging to a bygone era is an effective means to formulate a new and different identity. Cultural and educational institutions in cities like Toronto that represent important, yet-to-be-acknowledged hubs of modernist architecture need to likewise adopt a leadership stance on the international stage in galvanizing, like the city of Tashkent was able to do, attention surrounding their architectural heritage. The fact that it has yet to do so—and that several countries in Europe, like France—have a minority of classified buildings from the modern period hint to the fact that they have yet to formulate the future, and make away with the twentieth century to preserve it as safely belonging to the past. There is perhaps no more pressing time than now to excavate from the past the architectures that celebrate the modernist ethos of social emancipation and connectivity with nature to instigate a preservationist agenda geared towards the construction of a vision for ‘Man and his 21st century World.’