The first step in the transformation of the Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum) in Turin – in full celebration of its 200th anniversary – curated by OMA's David Gianotten and Andreas Karavanas in collaboration with Andrea Tabocchini Architecture, is finally up and running.

Replacing the “black box” layout conceived in 2006 by Dante Ferretti for the Winter Olympics, the new Galleria dei Re (Gallery of the Kings) rearranges the monumental statues of ancient Thebes according to a whole new idea of experience: evoking the historical context is the crucial point, together with the freedom for visitors to organise their own museum experience, and a visual continuity of spaces that aims to make the new Egizio a public space, a complex of “urban rooms” in communication with each other and above all with the city.

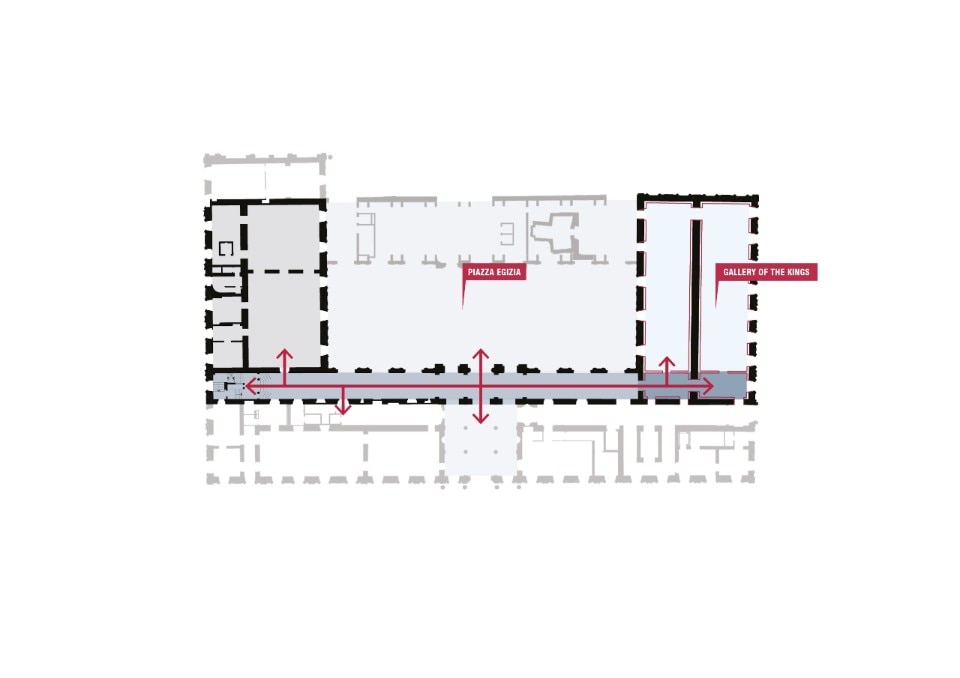

The Gallery project, in fact, despite being the first to see the light, is the result of a second competition won by Oma with Ata for the Museum, after the first one for the public space of the Piazza Egizia, with different brief and client, announced at the beginning of 2023 and currently under construction.

The new immersion begins with the curatorial concept of the entire project: a gradual transition from darkness to light, “a symbol of creation in ancient Egypt mostly associated to kings and gods”, through a dark entrance towards two large openings that frame the main rooms, this time brightly lit: “For us, it was very important to bring back daylight”, Gianotten told us.

The space then confirms the concept: the junction between the entrance and the rooms is marked by a lotus column, introducing the evocative spirit of the new Gallery.

The first ehibition hall in fact evokes the exterior of the temple of Karnak, announced by a couple of sphinxes facing each other, and developed into a procession of statues of the goddess Sekhmet, culminating with the statue of Seti II. The second hall, on the other hand, evokes the interior of the temple, in a parade of kings and gods that has revolving around the famous statue of Ramses II and closed by the gods Ptah and Amun.

The elements with which the architecture has given materiality to this experience are, in keeping with the designers' tradition, few and very simple.

The statues are now closer to the ground – “off the pedestal”, said Museum Director Christian Greco – as we had also seen in some of Oma’s installations for Fondazione Prada; the lighting changes from black box to a flood of natural light; the 17th-century ceiling is “revealed”, with its vaulted structure and openings; the walls are reflective, inviting a more concentrated appreciation of details, visual sequences, and continuity of spaces, from the Gallery to the city.

The language of forms, then, stems from a discourse of programme and process, as it has always been with Oma. The statues’ final layout is the result of a constant exchange with the museum’s curatorial team, for example, and here the pedestals – as they may be low, but they are there – play a crucial role: they are actually steel supports, with a structural glass back where necessary, embraced at the base by terrazzo elements that can be removed to facilitate moving the statues with a forklift. The aluminum reflecting walls, then, have a double mission: to bring people and artefacts together “in one mass, one experience”, and to allow the passage of an important network of installations, which has become necessary after the reopening of the windows on the halls, whose hygrothermal balance must be guaranteed.

Enveloped by nature

Conca, by Vaselli, is more than just a hydro-massage mini pool; it is an expression of local history and culture.