An explosive "wow effect" (starting with John Nash's eclectic Royal Pavilion in Brighton), the "marvel" of Baroque memories, and at the same time a deeper reflection on architectural language, technologies, materials and more generally on how to channel a specific system of values: designed specifically for great occasions, fairs and celebrations as "showcases" of the era in which they were built, pavilions were very often fertile grounds for design experimentation.

This is demonstrated by the many pieces of architecture that, while becoming icons of an era, have also set the pace in technological innovation and construction practice, from Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace, built for the London Expo of 1851 and the manifesto of emerging glass and steel technologies, to Frei Otto's German Pavilion for the Montreal Expo of 1967, which paved the way for tensile structures.

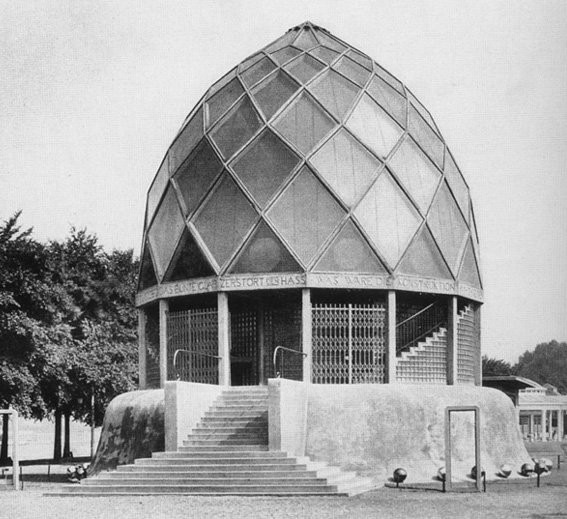

Among the many examples of pavilions – disappeared or in a poor state of health, rejuvenated, reinvented, or still shining like they used to do – we have selected some of the most successful demonstrations of balance between representational needs on the one hand and design innovation on the other: from those that have maintained their original function (Reed's Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne, Olbrich's Secession Palace in Vienna, Grand Palais in Paris, Mies van der Rohe's German Pavilion in Barcelona, Vitic's Pavilion no. 40 in Zagreb, Fehn's Nordic Pavilion in Venice), to those that have been reinvented (Buckminster Fuller's Biosphere in Montreal, MVRDV's Dutch Pavilion in Hannover, Foster+Partners' Alif Pavilion in Dubai); from those dismantled and reassembled elsewhere (Le Corbusier's Esprit Nouveau Pavilion in Paris) to those that have definitively disappeared (Taut's Glaspavilion in Cologne, Melnikov's USSR Pavilion in Paris, Le Corbusier's Philips Pavilion in Brussels, Studio Valle's Italian Pavilion in Osaka, Herzog&De Meuron and Ai Weiwei's Serpentine Summer Pavilion in London).