by Alessandro Benetti

The Bocconi Sports Center pool, designed by Sanaa, and the Cambini Fossati Sports Center pool, by engineer Carlo Rotellini for Technion, opened to the Milanese public just over a year apart, in late 2021 and early 2023, respectively. The Bocconi pool, crafted by an internationally acclaimed studio, is a contemporary masterpiece, impressive with its monumental double-height spaces and refined material choices, from the corrugated metal facades to the exposed concrete interiors. In stark contrast, the Cambini Fossati pool, conceived literally without architects, is a nondescript warehouse with an indecipherable urban presence and cramped, undersized spaces, if not by regulatory standards, certainly by practical ones.

The Bocconi pool features a 50-meter main pool that can be sectioned off with a movable barrier. The largest pool at Cambini Fossati is 25 meters with only six lanes. Both are open to the public, but Bocconi, which is privately owned and managed, charges twice as much as Cambini Fossati, a municipal pool managed by Milanosport. As a result, Bocconi often has few swimmers, while Cambini Fossati frequently reaches maximum capacity, leaving hopeful swimmers disappointed.

The missed opportunity of Cambini Fossati – a vital infrastructure in the dense, lower-income Via Padova neighborhood – illustrates Milan’s broader struggle to create high-quality public buildings. This issue is only partially due to budget constraints. It’s particularly disheartening because Milan is home to some of Italy’s most beautiful pools, established mainly between the 1920s and 1970s.

Milan is almost unique among European metropolises for lacking a seaside, lakeside, or major riverfront center. However, Milan can still aspire to be a ‘city of water’.

The Milanese pool system solidified during two key periods: the Fascist era and the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s. In both times, most public pools were designed by the municipal technical office, led first by Luigi Lorenzo Secchi (1889-1992), who served from 1925 in increasingly important roles, and then by Arrigo Arrighetti (1922-1989), who worked there from the early 1940s until 1979. Thus, Milan’s pools can be categorized into two distinct styles: Secchi’s early 20th-century, poetically De Chirico-esque pools and Arrighetti’s modernist, joyfully popular pools.

View gallery

View gallery

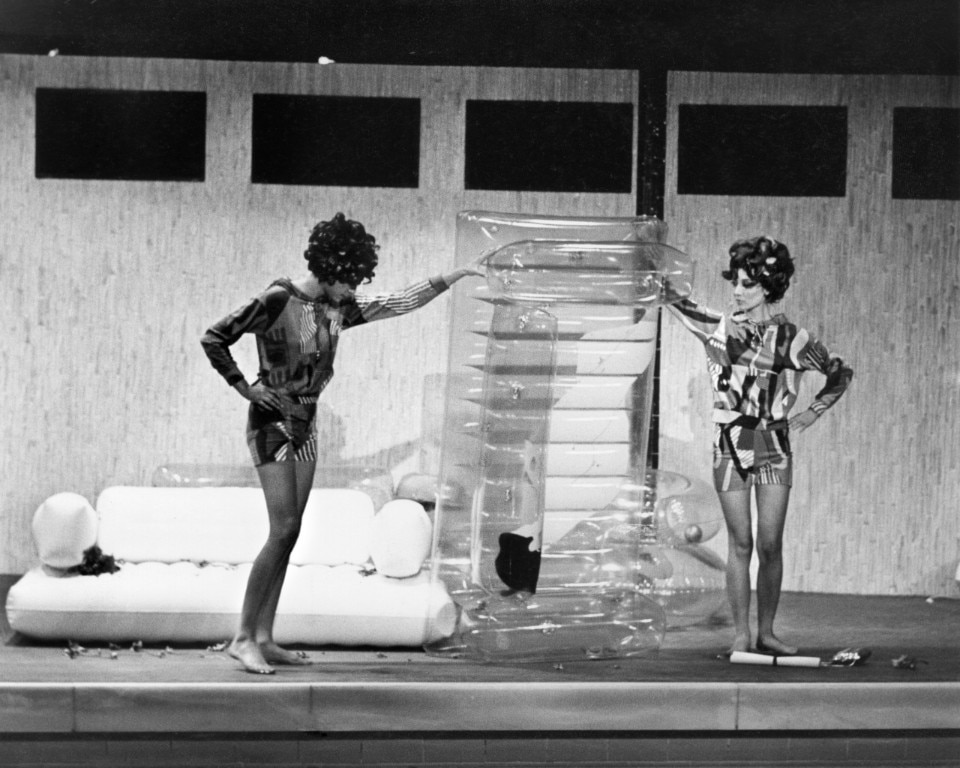

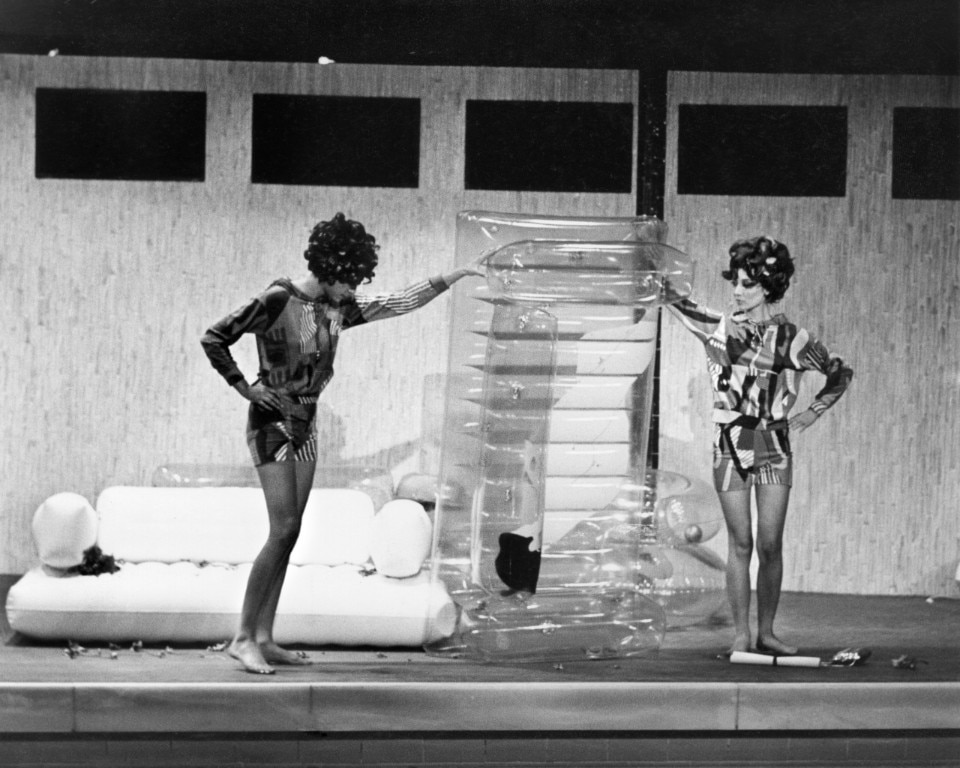

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

Missoni’s aquatic fashion show on inflatables, Solari swimming pool, 1967

Milan

Courtesy Missoni Archive

In the first category, we have the Romano (1929), where the three small pavilions of the former entrance, with their symmetrical layout and subtle decorations, set the stage for bathing rituals; the ex-Caimi (1937-1939), now Bagni Misteriosi, marked in the urban landscape by the tower and chimney of the austere brick building of the former public baths; and above all, the Cozzi (1933-1935), the largest with its Olympic-sized pool, the most luxurious with its Siena marble interiors, and the most avant-garde with once-transparent, openable skylights traversing its monumental barrel vault. Arrighetti’s works include the organic Argelati (1962), where both the volume of the entrance-bar, topped with a sun terrace, and the pool’s corners are rounded, clearly designed for leisure rather than competition; and the Solari (1963), an audacious yet friendly saddle-shaped tensile structure suspended in mid-air within its namesake park.

Adding to this bi-authorial core are notable works by renowned and lesser-known architects, such as Cesare Marescotti’s Lido (1931), originally private and inspired by American amusement parks, Pier Luigi Nervi’s Mincio (1964), with its coffered concrete ceiling appearing to float on a glass ribbon, and the Scarioni (1958) by municipal technical office architects Gino Bozzetti and Egizio Nichelli, elegantly streamlined in form.

View gallery

View gallery

This valuable heritage, oversized and inefficient by today’s standards, has deteriorated significantly over time. While the sophisticated restoration of Caimi (by Michele De Lucchi, Giovanna Latis, Elena Martucci, and Nicola Russi, completed in 2016) is commendable, it contrasts sharply with the clumsy repainting of Solari’s metal columns in garish colors, the mutilation of Romano, stripped of nearly all its original structures over the decades, and the substantial neglect of Argelati, Lido, and Scarioni. Simultaneously, new constructions fail to match the quality or quantity of their predecessors. The Cambini Fossati flop is a case in point, as is the long-delayed pool under construction in central Via Fatebenesorelle in the Brera district, which also shows little promise.

View gallery

View gallery

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Nari Ward and Beatrice Trussardi

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Radiant Smiles

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Gifted Witness

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Gifted Witness

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Stroller Sprouts

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Emergence Pool

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Nari Ward and Beatrice Trussardi

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Amazing Grace

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Radiant Smiles

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Gifted Witness

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Gifted Witness

Photo Marco De Scalzi

Gilded Darkness, Nari Ward, Fondazione Trussardi, 2022

Stroller Sprouts

Photo Marco De Scalzi

The decline of Milan’s public pool system is not just a source of understandable but somewhat sterile nostalgia for a time of greater and better investments in civic welfare structures. It’s a current issue because it represents a missed opportunity for Milan today and tomorrow, as of now. Architecture, urban projects, and environmental policies in Europe’s major cities increasingly focus on reconnecting with their waters, either rediscovered or long lost. In Oslo, people have been sunbathing on the artificial cliff of the Snøhetta-designed Opera House since 2007; in Stockholm, White Arkitekter recently redesigned the infrastructural hub separating Gamla Stan from Södermalm as a sun terrace straddling lake and sea; in Zurich, people have always swum in the Limmat, and since summer 2024, you can do the same in Paris, in the cleaned-up Seine, thanks to a €1.4 billion investment. The list goes on and on.

Milan is almost unique among European metropolises for lacking a seaside, lakeside, or major riverfront center. This is a significant disadvantage in times of climate extremes and urban heat islands. However, Milan can still aspire to be a “city of water,” provided it invests consistently and visionarily in two directions. First, it must enhance the multi-scale network of its numerous natural and artificial water bodies, stretching from the Ticino to the Adda, the large Alpine rivers marking its western and eastern borders, complemented by the Olona and Lambro, smaller and partly urban watercourses, channeled through radial canals – the Martesana, Naviglio Grande, and Naviglio Pavese – and finally expanding into the Idroscalo and Darsena basins. Second, Milan must urgently focus on truly public pools – affordable and accessible to all – as democratic, well-equipped neighborhood “epiphanies” of this wealth, by refurbishing the wonderful historic facilities and creating new ones that are equally luxurious and experimental.

Opening image: Piscina Cozzi, installation by Maurizio Cattelan, 2021