Six drummers and ten dancers stand tall and still as statues on the sidewalk outside Storefront for Art and Architecture, where the exhibition “Marching On: The Politics of Performance” has just opened. The 16 young African-American performers, all members of the Marching Cobras of New York, a Harlem-based group, silently hold their single-row formation for more than 10 minutes, letting the city flow around them, before bursting into action. As always, they dazzle their audience with well-coordinated sequences of rhythm and movement. At one point they pause just long enough to chant, “We ain’t playin’, we takin’ over, over.” At another point a police car sweeps by, blaring a warning to the overflowing crowd not to obstruct traffic on Kenmare street. The whole thing feels like an art party, but also a little bit like a protest.

View gallery

View gallery

Although the Marching Cobras have performed for international audiences and millions of TV viewers, Storefront’s “Marching On” is the first time they have found themselves working with architects. The project’s original choreography and costumes, accompanied by graphic and exhibition design, pay homage to African-American marching bands of the 19thand early 20thcenturies, composed of soldiers and veterans who used disciplined musical performance “as a means of critical leverage,” says Mabel O. Wilson, a designer and professor at Columbia GSAPP. “The association with the military was a way to be seen in public, and to also be seen as loyal to the nation, even though blacks didn’t have citizenship.” To parade was radical because it contained an unspoken bid for social equality.

At the invitation of Storefront director and chief curator Eva Franch i Gilabert, Wilson co-curated “Marching On” with architectural designer and scholar Bryony Roberts, who had previously collaborated with Chicago’s South Shore Drill Team at the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennale to stage a memorably militant performance called “We Know How to Order.” The duo agreed to lead a grand collaborative experiment in which a research project on the marching tradition would fuel an outpouring of new creative work. The resulting performance and exhibition is original and inspiring. Grounded in sober research and careful preparation, the show is full of joyful energy. It doesn’t form a seamless whole, and it doesn’t need to. Instead it consists of multiple layers and formats that intersect to create nodes of meaning—underscored by the sharp thumping of the drums.

View gallery

View gallery

The main series of performances associated with “Marching On” took place in November 2017 in Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park, a public space at the center of a changing neighborhood where soaring rents are driving out longtime neighborhood residents. The curators worked with Cobras CEO Terrel Stowers and Program Director Kevin Young to design a performance specifically for this contested location, parading from the street into the park, then out to the street again, symbolically reclaiming the public realm. What’s behind the Cobras’ choreography? “I dream it,” Young says. “Then we work it out piece by piece in practice.” In this case, the Cobras were asked to respond to spatial forms and patterns that Roberts and Wilson had identified in the park’s design.

View gallery

View gallery

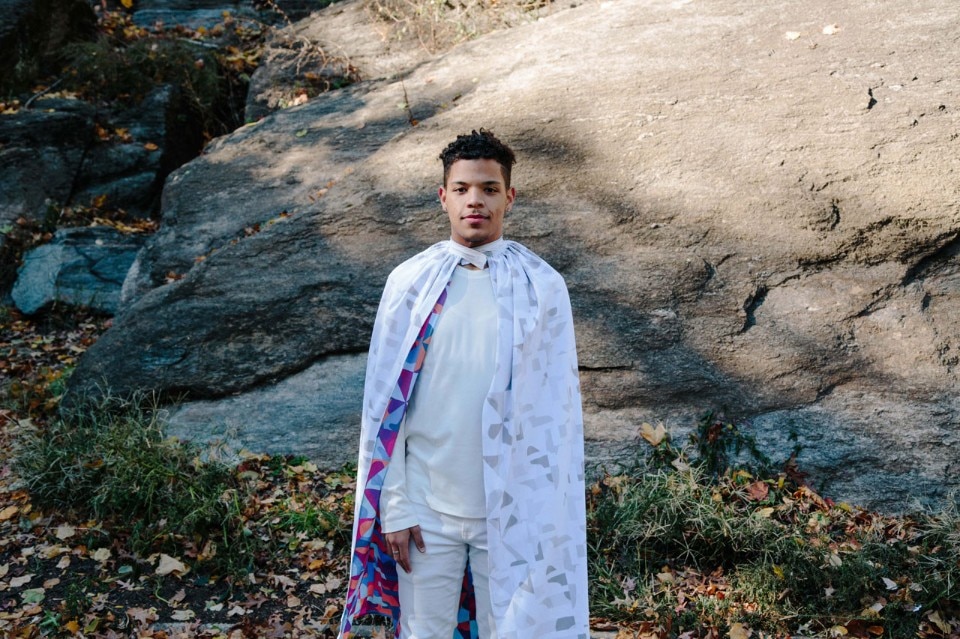

Roberts overlaid the rectilinear geometry of the park’s paving stones with fragments of military camouflage to design the eye-popping graphic patterns that adorn the costumes and gallery walls. These are meant to refer to the “Harlem Hellfighters” an African-American infantry regiment that fought with distinction in the First World War; and the 10,000 African-American children, women, and men who marched down New York’s Fifth Avenue, dressed all in white, in a 1917 silent protest march against racial violence. The Cobras’ newly commissioned performance was designed to become doubly camouflaged, Roberts says, as the parade retreated into the leafy confines of the park and the performers inverted their capes to expose alternate patterns. Back in the gallery, even the archival photos and documentary media in the exhibition are partially camouflaged by camo supergraphics and suspended triangular scrims that force viewers to duck and bob through the space.

This tension between invisibility and visibility, striving for recognition has been a long-running theme in African-American art. Today, racism in the U.S. is far from vanquished, and the spectacle of black youth marching and dancing in formation still carries the latent assertion of a collective right to public space.“Marching On” can be seen as an exercise in making visible the forgotten history of a vital kind of public performance art, one that is designed to produce moments of radical visibility for young people who may otherwise feel marginalized. To make it happen, New York’s architecture intelligentsia joined forces with a renowned community arts organization. It was a risk for everyone involved. But on opening day, everyone involved seemed to feel it was a success.

If the Cobras’ occupation of public space is fleeting by design, their conquest of the Storefront gallery will last through June 9. “Architects are always thinking about spaces for bodies in choreographed and organized ways. So I think it definitely speaks to the spatial sensibilities of architects,” Wilson says of the project. “Marching On” is one of the last major projects at Storefront to open under Franch, who has led the organization in 2010 and is departing to take the helm of the Architectural Association in London. Her role, she says modestly, was “just asking a question and bringing people together who otherwise would not have collaborated.” That is a simplification, but it accurately describes one of her core methods, one that has generated fresh programs and challenged architects to venture outside their comfort zone.

- Exhibition title:

- Marching On: The Politics of Performance

- Opening dates:

- 14 April – 9 June 2018

- Venue:

- Storefront for Art and Architecture

- Address:

- 97 Kenmare Street, New York