STARBOX 4160: Roller Blind Excellence

Mottura introduces STARBOX 4160: a system that marries sophisticated design and cutting-edge technology, for ultimate control of light and temperature.

- Sponsored content

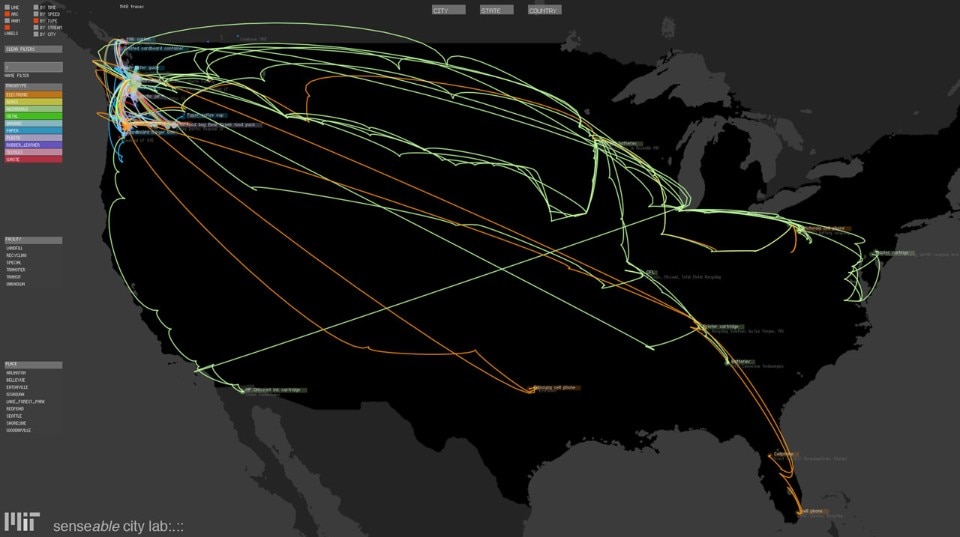

Architect and engineer, Carlo Ratti is director of the MIT Senseable City Lab and founding partner of design practice Carlo Ratti Associati – with branches in Turin and New York. His latest book is The City of Tomorrow (with Matthew Claudel). Meanwhile living in a connected world where available information is almost infinite, we are struggling to keep up without getting misdirected or trapped in superficial conclusions.

What is your definition of innovation?

I am a Schumpeterian at heart: I believe that human progress stems from “the doing of new things or the doing of things that are already being done in a new way”. Sometimes media represent innovation as necessarily related to the idea of tabula rasa. However, I think innovation should start from what is already existing – and aim to improve it.

View gallery

View gallery

With Australian developer Lendlease, you won the international competition to re-imagine Milan’s former World Expo site. The master plan envisions 1 million square meters’ theme park for Science and Technology. What makes this way of experiencing the city so innovative?

I think what we build today will last for the next 50 or 100 years. However, mobility will radically change in the next 5-10 years thanks to the advent of self-driving. So we tried to “future-proof” our masterplan: the streets of the site are accessible to self-driving vehicles, in a move that anticipates widespread changes brought about by autonomous cars.

View gallery

View gallery

What could be the result?

An increase in shared approach to transportation and getting more efficient and – more importantly – to have more sociable cities. Cars are idle 95% of the time, so they are ideal candidates for the sharing economy. Every shared car could remove about 10 to 30 privately owned vehicles form the street. Self-driving promises to have a dramatic impact on urban life, blurring the distinction between private and public. “Your” car could give you a lift to work in the morning and, rather than sitting idle in a parking lot, give a lift to someone else in your family – or to anyone else in your neighborhood.

View gallery

View gallery

How this project is it pushing the creative thinking forward?

I am excited about the concept “Common Ground” – a new type of public space to foster social experimentation composed by a two-floor high space all across the master plan. It is animated by a lively mix of plazas, pedestrian areas, pavilions, cafes, shared vegetable gardens, open galleries, laboratories, and retail. Even privately owned spaces will be publicly accessible. We have also incorporated different urban fabrics of Milan: its “magic” hidden gardens dating back to the middle ages, its vast 19th century boulevards and its more contemporary green immersed developments.

How could it affect the future of Milan, Italy and the world?

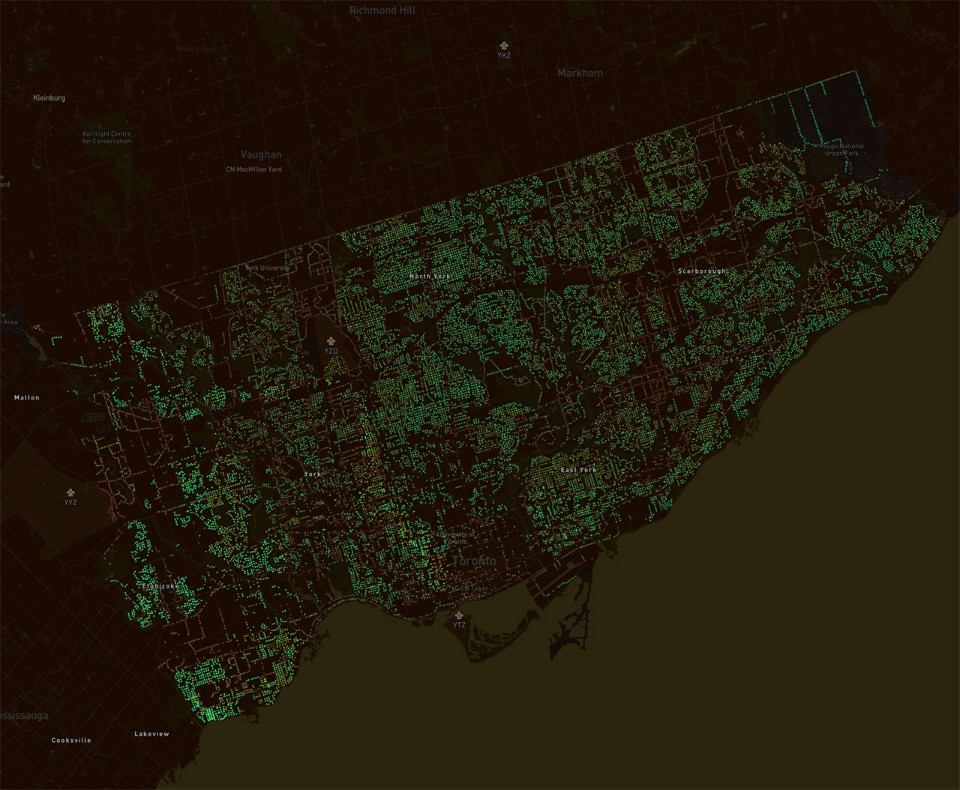

Innovation is becoming one of the most powerful urban engines around the world – as we can see through the increasing number of locations affixing the chemical element to their names: Silicon Alley (New York), Silicon Wadi (Tel Aviv), Silicon Sentier (Paris), etc. In Berlin, a new startup is said to be found every 20 minutes. Paris is busy building what will be Europe’s largest incubator at Halle Freyssinet. And in Tel Aviv, the phrase “Startup Nation” has gone from a political slogan to economic reality. Most likely, this proliferation of innovation is just the beginning. As the Internet continues its penetration of all aspects of our lives, we are entering what the computer scientist Mark Weiser has called the era of “ubiquitous computing” – a time when technology is so prevalent that it “recedes into the background of our lives.” Before long, the digital world and the physical world will be indistinguishable. The era of “Silicon Everywhere” is upon us – and it is taking shape in the world’s cities.

View gallery

View gallery

How communication is changing architecture?

As the IoT enters into architecture, our buildings and houses are starting to become increasingly adaptive. Architecture has often been described as a kind of “third skin” – in addition to our own biological one and our clothing. However, for too long it has functioned more like a corset: a rigid and uncompromising addition to our body. In the future, we could imagine an architecture that adapts to humans, rather than the other way around – a living, tailored space that is molded to its inhabitants’ need, characters, and desires.

Enveloped by nature

Conca, by Vaselli, is more than just a hydro-massage mini pool; it is an expression of local history and culture.

- Sponsored content

(1).jpeg.foto.tbig.jpg)