Lisa Licitra Ponti

“The brain has corridors” (Emily Dickinson) was the title I wanted to give to these notes on Arakawa the architect. But Arakawa says: “That is not correct. It implies the existence of one brain, but our body has several brains. Our hands, our legs, our feet have a brain. You know, Leonardo was looking for ‘where’ the mind is.” I’ll start from the notes made by Carla Pellegrini in New York a few months back, when she was preparing the exhibition in Milan and asking Arakawa questions. It is a treat to listen to Arakawa “live”.

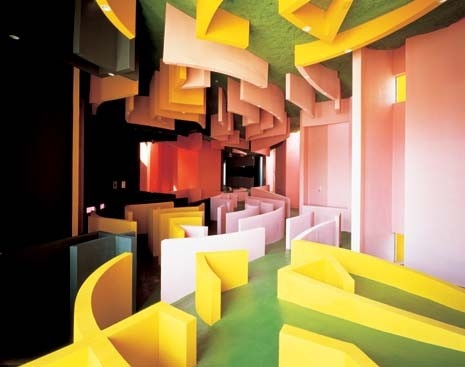

Better still would be to hear him here. Because it is not just an exhibition. Here Arakawa also proposes his architecture to those who can build it. It is an architecture intended to lead back to the “body”, hence the individual, the inhabitant, the “living”, while around us grow gigantic, hermetic “crystals”. It is a signal. Arakawa is a signal. And this is also due to his urge to want to “merge disciplines”, which is a brilliant hope. “Architecture ought to be designed for the actions it invites.” When Arakawa talks (to Carla) about “retirement homes”, he thinks of “destabilizing atmospheres in which the elderly should always be able to test their own faculties, and thus to discover them.” Arakawa: “Certain moves know me before I start moving.“ In East Hampton, in the Bioscleave House (or Angela’s House) that Arakawa is building, the oblique floor reawakens the sense of balance. Living is an active function.

One can think of a house as something “worn” like a skin, like “human snails”. The snail is an example of a perfect home: it clings to the creature that inhabits it, it is part of the person. Merz: “The concept of the home is the snail or the shell.” From the snail to the astronaut, what is the destiny of the species? “Architecture is the greatest tool available to our species, both for representing and re-inventing itself.” It builds for itself a “reversible destiny.” So say Arakawa and Madeline Gins. A thinking couple, Arakawa and Gins - he the artist, she the poet-philosopher - have designed together for years together. Their Architectural Body (2002), the book/manifesto that launched “an open challenge to our species to reinvent itself and to desist from foreclosing on any possibilities, even those our contemporaries judge to be impossible”, is a “renunciation of renunciation” (death is a renunciation of living).

Proper “architectural procedures” can produce an extension of life, as ‘medical procedures’ do. (Madeline might like to recast Heidegger’s statement “To be a human being means to be on this earth as a mortal; it means to dwell.”) And Arakawa: “You don’t fear war, you fear life…enormous fears of so many things…This sound, this environment scares you…They are not your scale…certain things expand your sense, they are taking care of you.” (Sottsass used to say that “the architect is the one who takes care of others.”)

I know that Arakawa studied medicine and biochemistry in Japan but what about painting? “Duchamp always urged me to re-invent myself, to always search” says Arakawa. Duchamp was the beloved “granddaddy” for Arakawa. When he arrived in New York as a young man, the two would often dine together. “I have not stopped painting or drawing, and maybe one day I will dedicate more time to this, but right now I am too involved in ‘architectural procedures’ and in ‘reversible destiny’ projects. The fact that an architect becomes a painter is more common. It doesn’t happen very often that a painter becomes an architect, but as I said many years ago (you remember, Carla), architecture is the most complete art, it’s the only art you can get inside of! My aim now is to build: houses, hotels, cities.”

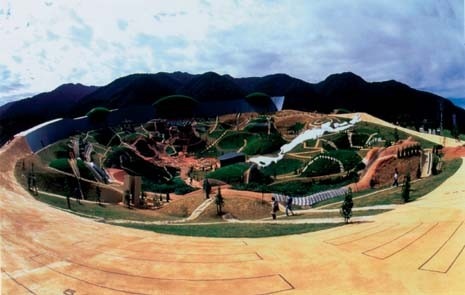

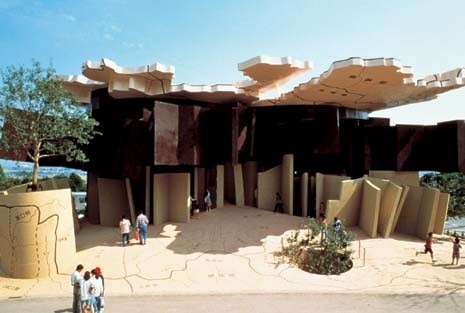

For Manhattan and for Atlanta, Georgia, Arakawa has designed his Reversible Destiny Hotels, which are places intended “to extend lifespan”, even during brief stays. For Tokyo, he designed “a whole city to be built on a river”. During the 1990s in Japan, Arakawa and Gins built a number of “architectural sites”, including the “ubiquitous site” of the Nagi Museum of Contemporary Art and the great Yoro Park, “a site of reversible destiny”, which are now historic places. Arakawa would like to build in Italy because it is Italy. “Leonardo understood everything. He understood that disciplines (art, literature, science and philosophy) had to meld to create life.

Consider his studies on the body and water. There was a project for Venice, when Cacciari was mayor, but we have not been able to realise it because the Fine Arts authorities only permit one to build in Venice with traditional materials.” Arakawa says that he would like “to design a satellite-town, something outside of Vinci, Siena or Bologna (when it comes to Bologna, where the first university was established, I think of Cofferati). The idea is to build using only prefab elements, like building a car body. The most philosophical house can be built like a car body.” It can be done. “Honda could make a room like this in two weeks. Industrialists in Italy could also do it. Imagine if Fiat would come and say, ‘We decided to do this house’. A car company knows how to make a car. They’ll just have to make it five times bigger”.

These are volcanic projects. “But volcanoes made countries, right? Even if is not true.“ Arakawa laughs. For the Milan show he is thinking of inviting a poet and only one art critic, and somebody, a star, presenting you and the project. Somebody outside the art world. “We, Italy, Milano. We have to make a drastic cut, Carla.“ There is, in fact, an “Arakawa contagiousness”. It is active and quite extraordinary. Enthusiasm is the first architecture and enthusiasm is also switching on a whole firmament of thinkers and poets, as Arakawa and Gins do. Pascal like Foucault, Einstein like Swift, in an atemporal continuity.

There is Calvino, too, who points to the trajectories and Agnetti who denies them. With enthusiasm Arakawa and Gins bring Europe closer. After years in America and Japan, the couple have been invited to Milan for the exhibition and to France for an interdisciplinary seminar. And in Domus they reappear (after a distant first publication in the 1970s introduced by Schwarz and Trini) with their most recent architectural project: the Reversible Destiny Hotels that are almost ready for use.

Outdoors: at the Milano Design Week, a new product by Nardi

With a patented system and durable, sustainable materials, Plano is Nardi's signature lounger designed by Raffaello Galiotto.