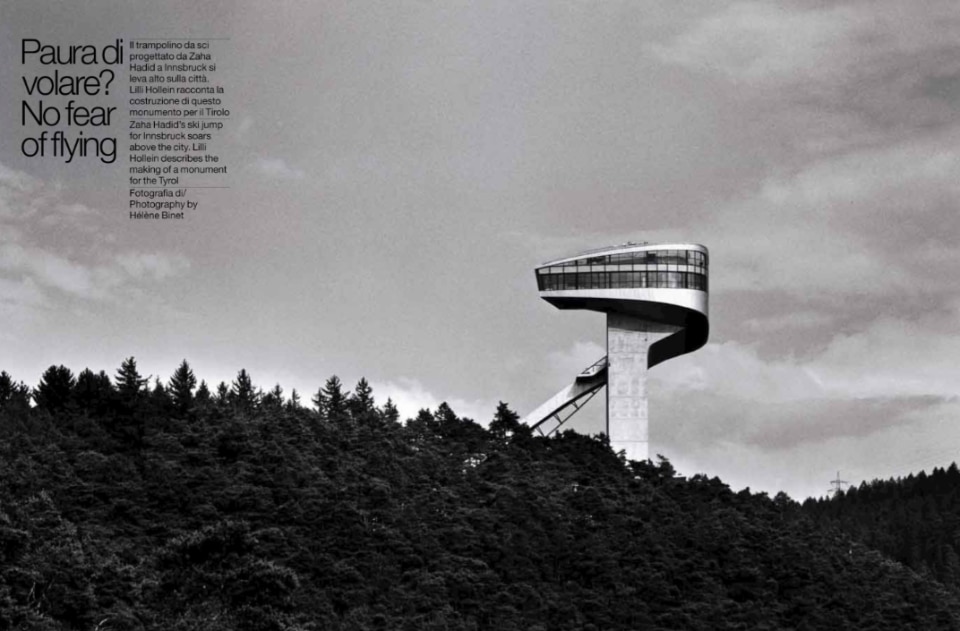

By the early 2000s, Zaha Hadid had positioned herself as the undisputed queen of the architectural star system, an image associated with the strongly sculptural shapes of her works, manifestos of an expressive gesture positioned between deconstructivism and parametric design. The geographies of architecture were also changing, with new cities and new landscapes appearing on the scene, where new works were applying for the status of instant icon as soon as they were completed. This was the case of the tower for the Innsbruck ski jump: Domus, which had been in an open dialogue with Hadid since the early 1980s, chose to publish the project in December 2002, on issue 854, with words by Lilli Hollein and images by Helène Binet.

No fear of fliyng

The people of the Austrian Tyrol are a tough lot. With an unshakable faith in themselves they have managed time and again to fight off hostile influences from the outside world that have threatened their secure alpine valleys. The Bergisel was the scene of one of the key events in the formation of Tyrolean identity. During the struggle for liberation, it was the site of an 1809 battle in which Andreas Hofer’s troops successfully beat back the Bavarians and subsequently, with less success, fought Napoleon’s army.

With this tradition of intransigence, it’s not entirely surprising that the Tyrol has also put up a lengthy rearguard action against contemporary architecture. In recent years, however, a number of remarkable buildings have gone up in and around Innsbruck to challenge this stereotype of cultural conservatism. Dominique Perrault has built a new city hall. There is a university building designed by Henke/Schreieck and an office block by Ben van Berkel.

But without a doubt, the most impressive of these initiatives is Zaha Hadid’s newly erected ski jump on the Bergisel. It combines sporty elegance and dignity in a structure of impressive lightness that does justice to the spectacular prominence of the site. The jump, actually a 50-metre-tall new building, stands on the site of a ramp originally erected as long ago as 1927. This earlier structure was regarded as something of an engineering achievement, making an impressive sight with its flight path toward the city of Innsbruck and its alpine backdrop.

It was upgraded to what were modern competition standards for the 1964 Winter Olympics. However, performances in this event have changed, and so have the demands skiers make on the facilities. While the world ski-jump record in 1928 stood at a modest 63 metres, a sensation at the time, the German ski-jumper Sven Hannawald achieved a new record of 134.5 metres on Hadid’s not-quite-completed ramp in January 2002.

The idea of replacing the existing structure had already been adopted and a first architectural competition held (without producing any outstanding results) when, at the end of 1998, a crowd panic at a snow-boarding event claimed five lives and the project was duly sped up. A second competition was held in 1999 and a budget of €13.5 million allocated for construction, which began in 2001.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Zaha Hadid has called her building an organic hybrid, a mixture of bridge and tower. It combines the ramp needed by the greatest skiers in the world with facilities for visitors who are less intrepid than the ski-jumpers. It offers them a chance to climb to the top, where they will find a café and viewing terrace. And in contrast to the spartan old days, they can do so effortlessly, by lift, as can indeed the ski-jumpers, who have a second lift of their own. The tower is made of exposed concrete with a finish of virtually Japanese standards. Its footprint is seven by seven metres, and it is about forty-eight metres in height, built with the help of climbing formwork. The top of the actual run is mounted on a projection, and an graceful circular movement unites the technical sporting elements – the platform and run – with the café and viewing platform to form a unit clad in steel plating. Poised in the landscape with its head raised, the structure looks out imperiously over Innsbruck. Like a snake or a fluttering scarf, the run itself wraps itself around the tower and then unwinds 90 metres down the valley.

Although competition conditions specified otherwise, it was found that there was no need to retain the struts of the old demolished ramp. Undergirding the section of the ramp where ski-jumpers still have the ground beneath their feet as they glide down, engineers solved the construction problem by borrowing ideas from bridge-building. With just one contact point, the ramp spans the distance from the tower to the arena vibration-free – an altogether elegant solution.

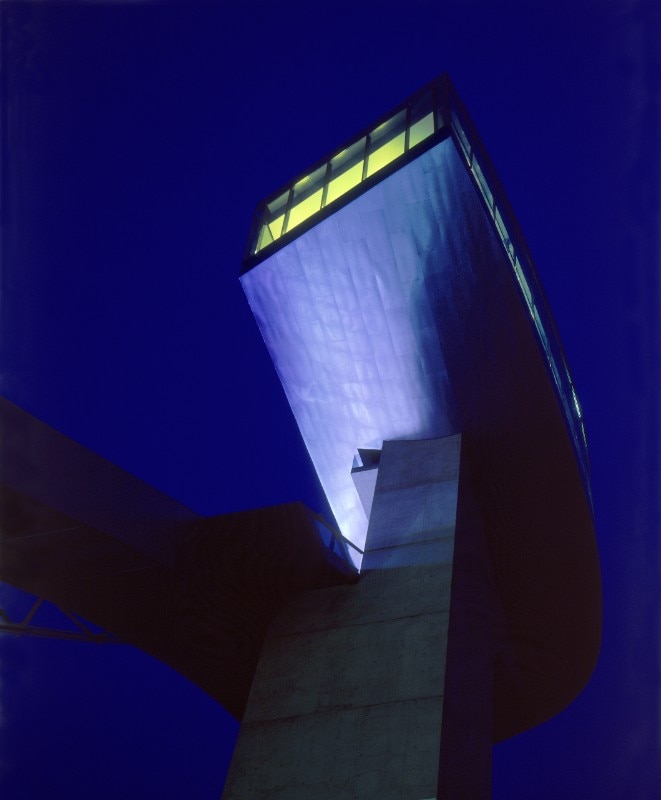

The head of the snake, which houses the restaurant, has also changed since the competition design. Hadid originally planned a sequence of windows, each larger than the one before, to direct the gaze of diners toward to the city of Innsbruck below. As realized, the 150-seat facility, with its panoramic glazing, now provides a 360-degree view of the spectacular mountain scenery. By night, the structure lights up. The ramp and the café interior change colour and glow intensely from the darkness.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Ski-jumpers gliding down toward the city and its picture-postcard backdrop are the main attraction, but even when there are no competitions taking place, the architecture, the food and the view all attract visitors. The same 360-degree effect is provided by the vista of the ramp and tower from the city centre and from the surrounding mountains. Every viewpoint opens up a new formal aspect, with different elements in the foreground each time. At the same time, the building fits harmoniously into the landscape, whatever the season. In the summer the structure provides a contrast with the green pastures and grazing cattle, in the autumn it sets off the foliage and in the winter, with its combination of exposed concrete and silvery metal cladding, it competes on equal terms with glittering snow and razor-sharp mountain silhouettes. Hadid has demonstrated her feeling for the right building in the right place.

Hadid’s realization of this sporting facility is more than just an aesthetic framework for athletic competitions. It is the architectural incarnation of the sensations experienced by the ski-jumpers. In a region where almost everyone has a strong relationship with sport and with the natural landscape, it has become a new symbol of the evolving Tyrolean identity.

Visual harmony and aesthetic

Now, more than ever, interior design is a balance of form and function, a dialogue between architecture, materials and finishes that transform and make the most of the space involved.