“Le vrai Moleskine n'est plus”, the owner of a Parisian stationary shop concisely stated to Bruce Chatwin, as indicated by the writer/traveller himself in The Songlines. Which is true, but also not. True, because the little dark cover notebooks produced by independent French bookbinders and used by artists and writers, from Hemingway to Picasso, had disappeared at that point. But untrue, because in 1997 Moleskine was reborn as a brand. Not in Paris, but in Milan. And it becomes a global cult, whose echo goes beyond the original it was inspired by. Daniela Riccardi, the new CEO, comes from Paris, where she was Baccarat's one for seven years. Previously Diesel's first CEO, she has “a very varied history”, as she herself defines it, with work experiences from Russia to China and Latin America.

Her way into Moleskine was not exactly usual. “I got to know my organisation through Teams and Zoom”, Riccardi says, who took office in April, “in the middle of the lockdown”. Our chat is by videoconference as well, as befits these times. And between a call for the smart working (“we support it with extreme flexibility, I don't see any efficiency problems, in fact maybe we are working more”, “this kind of flexibility is essential in a company as ours”) and statements of optimism (“if the world comes out of Covid, I don't see why we shouldn't come out of it with our heads held high too”), we immediately end up talking about the extraordinary rebirth of the diary during the pandemic, or as Americans call it, the journaling, “a term that has come back a lot among the younger generations, especially in the United States, but all over the world”.

Teenagers have restarted writing a diary.

I have a daughter of that age, I asked her what it consisted of. She explained to me that in such a critical moment, when you don't know what it will be about studies, work and travel projects, writing helps a lot. And it helps to go back and see what you were thinking six months ago, a year ago. I found this very meaningful.

Are you thinking about developing new products in this sense?

I have thought about it a lot and I would like to avoid doing it in a pathetic way.

Meaning?

I don't want it to be the diary of the Coronavirus years, but something about how we rewrote our history. I think it's a theme. I don't know if we'll come up with a new product, or if we'll just introduce something into what we already have, by communicating with our online communities.

What's the Moleskine community like?

Bigger than we imagine: one part is “sponsored”, and that's part of our history, then we have an archive of thousands of pieces developed by artists, the Moleskine that they gave us. And then there are spontaneous communities.

On social networks?

For example, on TikTok where tens of millions of young people exchange their art using the hashtag #ourjournal and most of them do it using the Moleskine. I'm trying to understand how much it makes sense to sponsor and how much this thing should be left to its spontaneity.

That's right. Many brands sometimes don't understand that by insisting on placing their product or logo, risk a boomerang effect.

In the communities sponsored on TikTok, you feel that a brand is there pushing to sell. And so, it seems to me that the real meaning of the brand comes out trivialized. I would like to amplify without getting to the sponsoring.

Influencers should be employed carefully.

This whole influencer thing gets to a point where credibility is questionable.

.tif.foto.rmedium.jpg)

This whole influencer thing gets to a point where credibility is questionable

What about the archive?

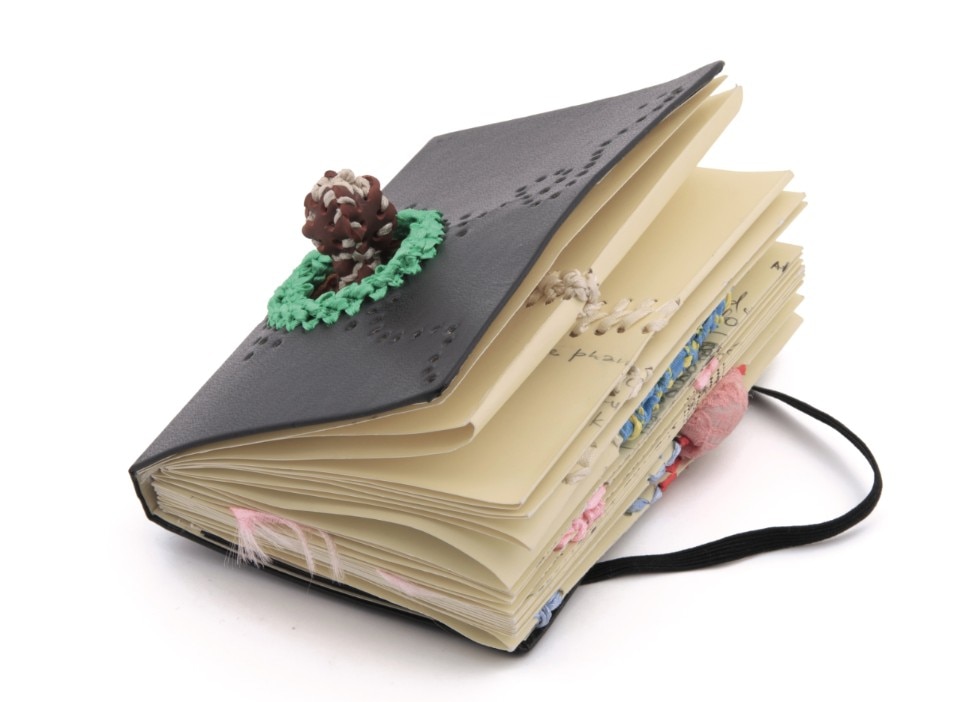

In the Moleskine Foundation archive, there is a collection of thousands of pieces. Some of them come from a series of travelling events called Detour. About fifteen years ago in Shanghai, when nobody was going there yet, we were among the firsts to do something like this; in that context we talked about the beauty of writing on paper, and various artists created works that were then donated to the archive. A treasure, an incredible and essential value. I would like to do many things, even create re-editions of those pieces, for instance to have a copy of a particular artist's notebook, his own, what is often said in our world, “my Moleskine”.

So, we get to the point: the fact that Moleskine's value goes beyond the product, the notebook.

It is beautiful and that is why I am here. Moleskine is a beautiful company that was born and raised with the aim of making a design product for a cultural project, and so it is still today.

The cultural aspect is crucial, right?

Yes, it is. We are not a notebook; we are a story to write. A force that must help human genius, which expresses itself through the stroke of the hand and the pen on the paper, in order to impartcreativity in the most immediate and productive way. Everything we do revolves around this in a very organic way. We do not sell notebooks; we sell a book yet to be written.

Even if you don't have to be a writer to use it. Who uses your notebooks today?

Among our clients there are many professionals: creative people, but also lawyers and notaries, digital professionals. And they all tell a story about Moleskine's collections. For Maria Segregondi, the founder, the word “creative” is not restricted to those who design or make comics or advertise and as she says, these are the new Chatwin, the new Picasso, the new Hemingway, which express themselves in a more widely way than it was in the past. I can't even say that we work with designers because they are the ones who work with us.

The French think Moleskine is French, the Americans American. So how important is Italian spirit?

The product was created with an attention to detail and quality, in design, in the type of paper and its colour, in the finesse of the details, in the curvature of the corners, with that tension towards beauty that is part of Italian culture.

But it is also a global product.

The product was designed here, then in China thanks to the paper, calligraphy and bookbinding experts, the right elements were chosen to produce it. It is global in every way.

And for me, who have lived so many years in different cultures, Italy is certainly not in the centre of the world and we must understand others and get closer to them. It's something I care a lot about.

Does the excess of pride that some of our companies have for Made in Italy is likely to become a cage, in a world where value is often created through interaction between cultures?

We Italians have brought an artistic sense and attention to detail and quality in fashion or furniture design that are important. People abroad are keen to emphasise that their clothes are Italian, their furniture is Italian. I also think that from an entrepreneurial and business expansion point of view we have to confront other realities. Maybe it is easier to enter the market because it brings the value of being an Italian brand, but then it is not enough. Abroad there are many brands that claim they are Italian, but we have never heard of them in Italy. A bit like the chicken lasagne they eat in Colombia, surethat it is an Italian dish. Italian spirit sells, it is “used, abused and misused”.

Moleskine is a beautiful company that was born and raised with the aim of making a design product for a cultural project, and so it is still today.

Is there something from your experience in fashion that you want to bring to this new one?

I started using Moleskine as an accessory to match this bag, that scarf. Or according to the colours of the year. Surely it is born as a design object and that has aesthetic elements in its DNA. Now there is a Frida Kahlo’s limited edition, which comes after the studio collection that brought together 6 different talents from all over the world. I think there will be more and more space for colours, materials and, why not, partnerships. But what's important is that Moleskine must never be fashionable and go out of fashion. This is a company that has not let itself be pulled left and right by the trends of the moment, is very focused on its aim, and is extremely present in everyday life.

As Lego, you are a company that was born analogue, but digital is very good as well.

An important part of our business is the smart writing system, a part I will be insisting on in the coming years. It's perfectly Moleskine, because you write on paper, but what you do can amplify it on the digital world.

Is this your way into the future?

It's a language that makes sense by looking at the coming years, where we want the world to rediscover the importance of the human genius gesture expressed by sketching something on a piece of paper, which maybe then turns into a huge project, but which has to start from there. And I think there is a lot of science and literature that today tries to make the new generations rediscover the importance of not losing that aspect. This speaks of the Moleskine project longevity too. We have not seen a decline in our more or less 10 million users.

Moleskine is a series of apps as well, such as the Timepage or the Flow calendar, which was awarded an Apple Design Award last year.

It was born from a real digital project, with a team scattered between Rome, Australia and the United States that did an excellent job. In the future we will try to develop apps even closer to the brand's DNA. My challenge, my request, has been to think of applications that stimulate cultural, artistic and design recognition, which we can integrate into the Moleskine ecosystem. They will never replace the notebook, but will serve to amplify, zigzagging between digital and analogue and bringing out the best of our potential.

An increased Moleskine.

We need to find a way to seamlessly integrate analogue and digital, yes, we need to. Without having to leave something on one side or the other.

Opening image: Nicholas Hlobo (Cape Town, South Africa 1975) - Untitled 2009. Detour Project, courtesy of Collezione Fondazione Moleskine.