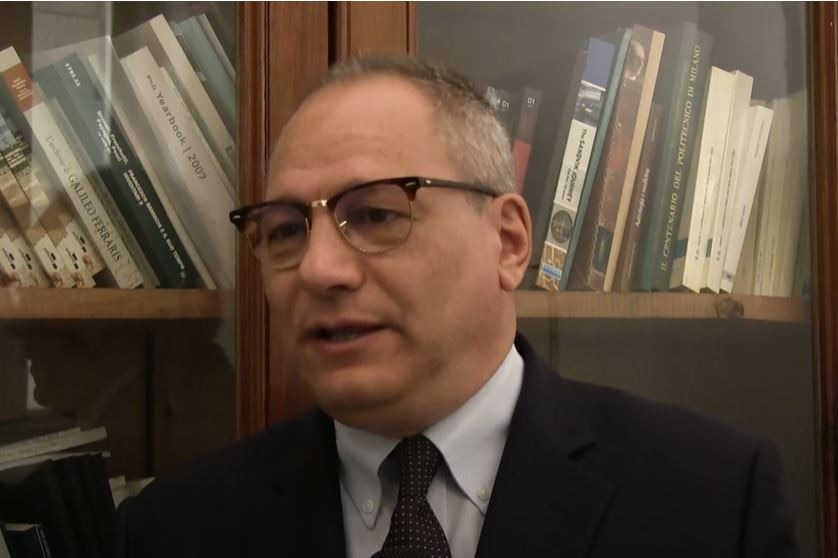

The legacy of Federico Bucci, who died tragically at the age of 63, is the legacy of a prolific and sharp architectural historian, embracing his research on figures such as Albert Kahn, Luigi Moretti, Franco Albini, and his teaching at Politecnico di Milano, directing the Mantua campus since 2011, consolidating it in its quality as a school of architecture and a central reality in the cultural life of the territory (Domus had dedicated pages in 2017 to the MantovArchitettura project). But also part of his figure was the nature of a refined observer and great communicator, a critic capable of highlighting the fundamental themes underlying projects, research and debates. For Domus, with which he collaborated for over three decades, Bucci signed reviews that, starting from the books they presented, extended into as many lively lectures and arguments of absolute effectiveness. To remember Bucci, let us return to the text he dedicated to the figure of Reyner Banham, on issue 850, in July 2002.

Federico Bucci (1959-2023) for Domus: on Reyner Banham and the history of immediate future

We remember the architectural historian and pro-rector of the Milan Polytechnic, recently deceased, through the words of one of his illuminating and sharp reviews, which accompanied many years of our magazine.

View Article details

- Federico Bucci

- 19 September 2023

Was Reyner Banham the ‘historian of the immediate future’ or the ‘curator of Frigidaires’? The first statement is acknowledged internationally, while the second relates to a famous argument he had with Ernesto Rogers. In the 1950s, Banham, a combative contributor to The Architectural Review, was engaged in a heated debate with the leading exponents of Italy’s architectural culture. Despite their evident semantic conflict, these two descriptions of Banham from different sources provide excellent definitions of the intellectual career of one of the last protagonists of ‘operational criticism’. There is great need for it today, to shake up the muddy, globalized world of contemporary architecture. The usual stars (who have not changed) complacently rule the roost; they are feted everywhere in exhibitions, books and journals without ever having had their creative production subjected to serious critique. So it is a pity that this excellent project by Nigel Whiteley, who carefully and scrupulously reconstructs all of the complex issues and problems tackled by Reyner Banham in his nearly 40-year career, does not devote enough space to his relationship with Italy.

The British historian and critic’s range and intellectual thrust were both wide and deep, inviting a comparison with the current weakness of architectural criticism. But perhaps we are too biased – and not just because we would like the events of a chapter of Italy’s architectural history to be amplified. From this fresh strand of architectural historiography we expect a certain maturity (or a healthy ingenuity) that would invite architectural history to move out from its stranded position in extremely dull archival chronicles. Instead, it should address the dangerous and fascinating adventures of interpretation.

‘History is, of course, my academic discipline. Criticism is what I do for money’, said Banham, with his usual irreverent polemical posture. Perhaps, as Whiteley comments, this stance was intended to separate clearly Banham’s two primary activities. As an historian he taught at university and authored books that have now become classics, including Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment and Concrete Atlantis. Infinite articles published in the trade (and other) journals testify to his other role, as a militant critic of the European and American architectural avant-gardes. Yet Banham’s style never changed, whether he was grappling with erudite historical research or taking a stand on contemporary events. It was always direct, intelligently provocative and, above all, a far cry from the technical jargon that often masks the lack of ideas. One instance occurred when he stated his own ‘transatlantic’ viewpoint on the reuse of the Fiat Lingotto plant in Turin. With uncommon courage and frankness, in Casabella he spoke out in favour of an honest demolition, which he considered preferable to witnessing the conversion of the glorious building into a ‘cultural’ supermarket.

That took place in 1984. The year before, Banham’s 1971 book on Los Angeles had been translated into Italian, initiating the prolific ‘American chapter’ that was to characterize the last 20 years of his life. At the time Banham worked closely with Casabella, edited by Gregotti, writing articles about Silicon Valley (no. 539, October 1987), the Tennessee Valley Authority dams (no. 542-543, January-February 1988) and other subjects. This series of articles almost seemed to be making amends for what had happened back in 1959, when, as editor of Casabella, Rogers violently attacked Banham, branding him the ‘curator of Frigidaires’ because he had called the neo-Art-Nouveau movement ‘the Italian retreat from modern architecture’.

Now, over 40 years later, looking back on the debate (one of the last examples of free architectural criticism), Banham’s accusations of romantic nostalgia against Milanese and Turinese architects were surely not intended in defence of the orthodoxy of the modern movement. Rogers demonstrated (Casabella-Continuità, no. 228, June 1959) that he fully comprehended by barely touching on the core of the question raised by the British critic. In fact, in his famous article in The Architectural Review in April 1952 (translated into Italian in Comunità, no. 72, 1952), Banham dwelt on the architectural quality of the Roman school. In particular, he praised the work of Luigi Moretti, to whom he had already paid tribute in a piece devoted to the Sunflower House (The Architectural Review, no. 113, February 1953). Rogers’ reply was resentful: ‘[Moretti’s] formalism is able, but it is a pipe dream; it does not indicate the presumed goals unattained by us. Moreover, it negates the theoretical and, above all, moral presuppositions of our struggle against aestheticism and intellectual games’. Clearly Banham had hit the mark, putting salt into the wounds of the wholly Italian political battle. It was between Rogers’ ethics (which had been through the post-war ‘catharsis’) and the undeniably modern creative freedom of a difficult figure like Moretti, an unrepentant fascist. There is no mention of this in Whiteley’s publication, but he cannot be blamed.

This worthwhile book usefully reflects on Banham’s work. The historian did not accept easy interpretations, and as a critic he boldly fielded his lively affability on the side of knowledge contemporary art.

Reyner Banham: Historian of the Immediate Future, Nigel Whiteley, The MIT Press, Cambridge Mass./London, 2002 (pp. 494, s.i.p.)