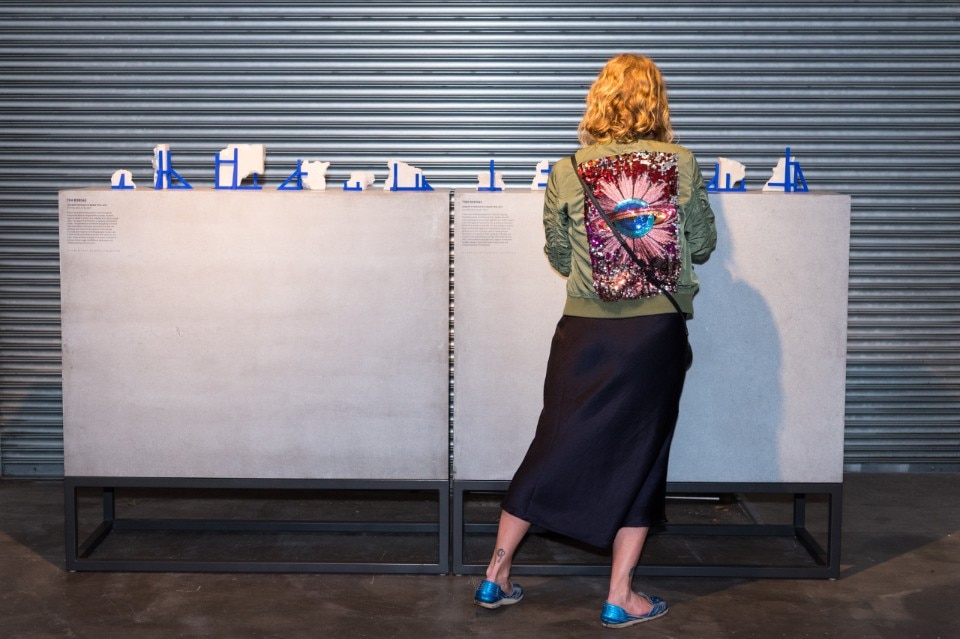

Curated by Margaret Hancock Davis and Brian Parkes from JamFactory in South Australia, “Concrete: art design architecture” explores the history and meaning of the material and its applications. The 21 artists, designers and architects involved have created a wide range of concepts for expressing concrete’s manifold expressions from jewellery to building and sculpture. They do this using a variety of strategies, such as using the effect of the duration of the exhibition on the material as it tours Australia to call into question the use of concrete in construction processes.

Many of the works in this exhibition play with concrete’s soaring, sculptural qualities. “Hawthorn House” by Edition Office is perfectly integrated with the surrounding landscape, made with steep curves and glass surrounded by green foliage which offset the intensity of the concrete structure. The structure’s curves give it a sort of grace, while the sightlines that penetrate the building give it an appearance of suspension in the air.

Concrete is a builder’s chameleon, as strong as stone but taking any form. In Western Australia “Margaret River Youth Precinct” is a cast concrete skate park built by Convic in 1999 and redeveloped in 2018 and fashioned after the waves and surf culture that make Margaret River famous.

Concrete’s monumental force and its ability to appear almost weightless give three religious buildings an aura of divinity, including Glen Murcutt’s “Australian Islamic Centre” 2016 and Angelo Candelpas designed “Punchbowl Mosque” 2018, the latter which uses concrete’s sculptural qualities to create a series of repeated patterns, monuments to the Islamic faith in Australian suburbia. Likewise Baldasso Cortese’s “Tarrawarra Abbey” 2016 provides a refuse to monks in the Victorian landscape of the Yarra Valley, using the textured surfaces of concrete embedded with embossed crosses create an atmosphere of “clarity, permanency, confidence and calm”, as Leanne Amodeo describes it.

A number of artistic works maintain the spirtual themes made possible by working with this famously utilitarian material. Quandamooka artist Megan Cope’s “RE FORMATION”, recreates middens of case concrete oyster shells, repopulating sites stripped and mined by the colonisers. Kyoko Hashimoto and Guy Keuleman’s “Large Prayer Beads (Daijuzu)” 2018 made in concrete with steel rebars degrade over time, gradually disintegrating over the course of the travelling exhibition as humidity and oxygen cause the steel rebar in reinforced concrete to rust. The artists refer to by non-western ways of conceiving time to provoke the audience to question our expectations of planned obsolescence.

Focusing on the life cycle of concrete seems particularly apt as it is not certain that concrete will continue to be viable in the future. As reports by BBC Future tell us, one of the key ingredients of concrete and the world’s most in demand natural resource after water: sand is running out. Moreover the International Energy Association claims it will be difficult to meet the high demand for concrete while finding ways to combat global warming. One of its key ingredients, cement, is responsible for 7% of global CO2 emissions. In June last year the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, which represents investors worth $2 trillion, released a statement pressuring the cement industry to go carbon neutral by 2050, challenging them to come up with new ideas and technologies. Perhaps this was the intention of the peak body for the cement industry Cement Concrete & Aggregates Australia, with their decision to become the principal sponsor of this exhibition.

There is no doubt concrete is an impressive material, equally solemn and sturdy. But if, as Craswell suggests, concrete is a material capable of “sublime transformation”, then there could have been more of a curatorial focus on what it will become, either through innovation or changing circumstances.

An artist who considered this question is Jamie North. His work “The Remainder” employs the waste from industrial production like blast furnace slag and marble dust as well as steel. In Remainder No. 12 (Incline), a sphere impossibly suspended in motion on a slanted plank, calls to mind the unstoppable forces of gravity, atrophy and time. In Remainder No. 11 and No. 10 Pyrossia plants sprout from the degraded spherical forms. “I’m interested in a continuum, not binaries,” North says, “[N]ature and human enterprise don’t have to be in opposition. There is opportunity for compatible systems and structures”.

- Exhibition:

- Concrete: art design architecture

- Curated by:

- Margaret Hancock Davis and Brian Parkes

- Where:

- Australian Design Centre

- Opening dates:

- 31 January - 18 March 2020