Until the debut of the PlayStation in 1994 – Sony's flagship product, now celebrating its 30th anniversary – all Nintendo (and non-Nintendo) home consoles had centered their TV commercials on showcasing the product itself. These ads typically featured enthusiastic gamers holding the consoles, emphasizing the excitement of playing and celebrating the characters of various video games, often blending them with real-world scenarios. But all their commercials always prioritized the product – whether a video game or console – as a status symbol for gamers rather than focusing on its technical features.

Gameplay sequences were often only hinted at. This aimed at maintaining an air of mystery around the purchase while masking the technical limitations of the time. Visually compelling gameplay moments could be counted on the fingers of one hand, and players often had to deeply rely on their imagination. Within this framework, rooted in the 1970s and 1980s traditions of home gaming, the arrival of the PlayStation in the 1990s marked a significant shift in communication strategies.

Drawing on two decades of industry experience, the Japanese production company ushered in a new era of television advertising. Moving beyond the simplicity of children sharing games and daily situations, like Game Boy commercials highlighting its portability – while conveniently glossing over its appetite for batteries within a small amount of time – Sony's marketing embraced an entirely new dimension: 3D complexity.

Before this shift, Nintendo's ads had relied on trendy protagonists and fresh imagery – some Italians may recall versions Topolino comic series featuring Jovanotti at the height of his fame, among others. How to overcome that kind of language? How to reinterpret through the contemporary canons of that time something functional and established? To understand this abrupt paradigm shift, we must examine the fundamental difference: What set the PlayStation1 apart from all other gaming consoles right from the beginning? It was its computing power and the resulting superior technical quality of its game library.

This approach was a natural evolution from video game packaging of the previous decade, from the mid-1980s to the mid1990s, which featured large paper or plastic packages, already showing something from the game within, with more or less effective screenshots and descriptions about the content. But as decades passed, media stated to overlap, and communication styles changed. Entering a saturated market in communicative terms, Sony recognized that merely imitating the existing advertising language would have worked, but it would likely have caused confusion among buyers.

All their commercials always prioritized the product as a status symbol for gamers rather than focusing on its technical features.

Among its many achievements, the Japanese giant understood that it no longer needed to minimize in-game footage in its promotions – quite the opposite. Those images had become what made the PlayStation revolutionary and its selling point, aligning perfectly with the desires of a new generation of gamers. The whole world was in fact charmed by the ads for Final Fantasy VII, which showcased its cinematic 3D graphics that felt groundbreaking at the time. Drawing a parallel to the film industry, this was akin to the transformative immediate impact – or at least of contemporary development – started by DreamWorks, which heralded a new era of “real” 3D visuals – not the pseudo-3D effects of the late 1980s – with the animated movie Antz.

Tra i grandi meriti del colosso nipponico c’è l’aver capito, di colpo, che era diventato inutile - anzi, limitante - ridurre all’osso le immagini in-game da mostrare, perché esse iniziavano a rappresentare proprio quel punto di forza e innovazione tanto cercato dalle nuove generazioni di giocatori. Tutto il mondo è rimasto affascinato dalla pubblicità di Final Fantasy VII, che riprendeva l’introduzione del gioco con quella grafica 3d che profumava di nuovo. Per fare un parallelismo cinematografico, parliamo di una reazione immediata, o quantomeno di sviluppo contemporaneo, al trend d’animazione iniziato poco tempo prima da Dreamworks, che a partire da Z la formica aveva aperto il Vaso di Pandora della terza dimensione “reale”, non più simulata dal falso 3d proposto sul finire degli anni Ottanta.

At the same time, to honor its heritage, innovation also followed a more traditional formula: showing audiences just how much fun video games could be. In this regard, it’s impossible not to mention the equally catchy commercials for titles like Crash Bandicoot (each installment in the series featuring increasingly wilder and zanier ads) and Twisted Metal, both leaning heavily on themes of frenzy and fun above anything else. Starting in 1996, this lighthearted, surreal, and easygoing approach became a defining element of the Nintendo 64’s success, where characters like Pokémon, Link, and Mario often shared the screen in the same commercials. Suddenly, Nintendo’s undisputed innovation seemed to follow – though in its own way – a trend pioneered by its competitors. This rivalry sparked a wave of experimentation.

Aesthetically, the advertising landscape of the late 1990s and early 2000s can be divided, without hesitation, into two distinct eras. The first wave, extending from the early 1990s, saw an explosion of commercials that seemed tailor-made for MTV: with a 4:3 aspect ratio, hyper-saturated colors, and wide shots, just like many of American music videos of the time by bands like The Offspring, Green Day, and Blink-182 to name a few. However, the turning point came with the rise of The Matrix and its unsaturated, minimalist aesthetic, marking the beginning of a shift that would dominate the late half of 2000s and the early 2010s.

Beyond the nostalgia these commercials evoke for those who were just entering adolescence at the time, their sheer effectiveness of these vivid explosions of color, sound, and energy is undeniable. Before the mid-1990s brought a darker cultural tone – when global conflicts and widespread fears began to erode the innocence of millions of Western kids – advertising seemed to revel in a kind of boundless creativity, raising the bar with each campaign and new product, producing a promotional golden age that still remains unmatched in advertising history.

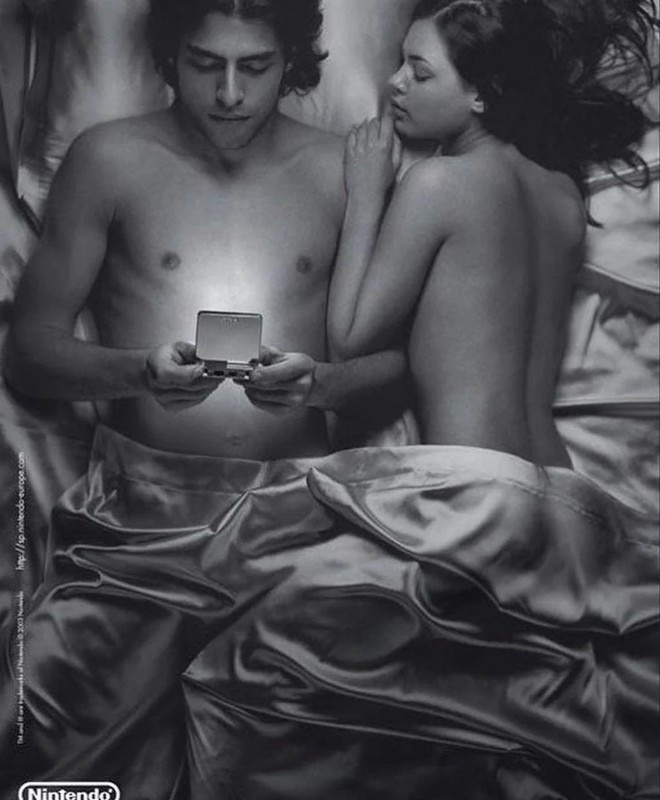

Opening image: an ads by Gameboy in the 90s. Courtesy Nintendo

Bathed in light

Drawing from its more than 30 years of experience, SICIS introduces backlit pools in Vetrite, a patented solution that combines design, technology and function.