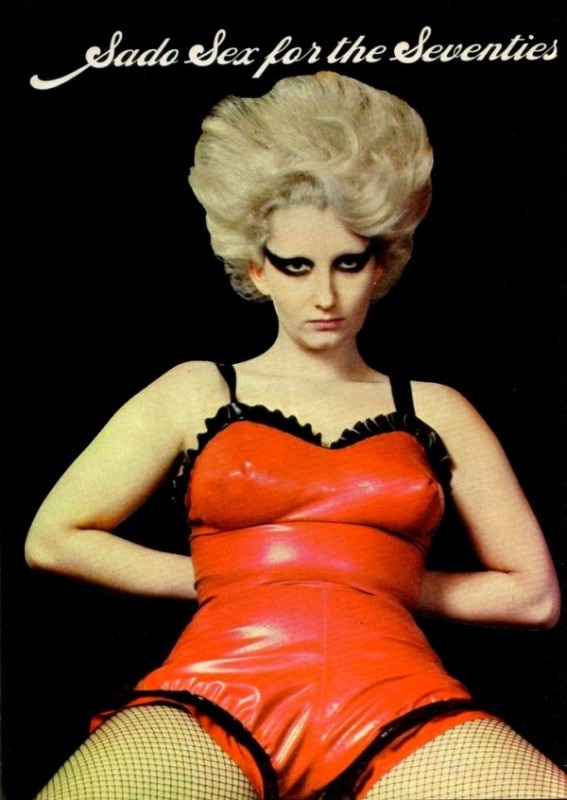

In a famous photograph from 1976 that immortalises the pastel pink facade of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s boutique in King's Road, Chelsea, one can spot a female figure standing on its door. Her look is defined by a blonde Atom Age beehive and a black bodysuit, as tight as sharp is her makeup. Next to her, a middle-aged man, in a suit, stares perplexed. She is provocatively dark and young, he appears as passé as his flared suit. They look as if they belonged to different eras, highlighting a generational transition that only design applied to fashion can make visible.

Behind her is an immense sign wrapped in pink silky fabric: SEX. This is the name of the shop that once sucked the customers into its semi-darkness – almost a metaphor for the female sexual organ – offered a selection of garments equally inspired by the mid-’70s nostalgia for the 1950s and by bondage and fetish culture, including latex pieces, gimp mask and safety pins.

The girl, in her early twenties, is Jordan Mooney, born Pamela Moore. Hailing from Seaford, in the peaceful county of East Sussex, Mooney couldn’t choose a more different life than that of her upbringing, embracing the burgeoning punk scene and becoming one of its immarcescible and most genuine icons until her death, which occurred yesterday at the age of 66.

Friend and model for Vivienne Westwood, who jointly with her then partner Malcolm McLaren was radically subverting British youth fashion, Jordan embodied a physical extension of the two designers' visions on the streets of Chelsea.

A commuter, Mooney would travel daily from the Sussex coast to London to work in the boutique. Needless to say, her PVC outfits were dangerous provocations in the eyes of the passengers. Thus British Railway – as the girl recalls in an old interview for the BBC – allowed her to travel first class with a second class ticket, to protect her or, perhaps, the sanity of fellow passengers.

The same iconic shot was recently used for the artwork of a compilation album (SEX: Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die) curated by Marco Pirroni (founding member of Siouxsie & The Banshees) and reproposing the tracks that played on the boutique’s juke box, next to which Jordan was many times portrayed. Surprise: no punk, though, lots of ‘50s rock 'n roll and Texan psychedelic garage. After all, those songs as much as this photograph serve to frame and narrate – better than many others – what punk was: a situationist flash, before it ended up swallowed by its own intuitions.

Punk was, above all, art, applied now to fashion, now to music and performance. And Jordan Mooney was its undisputed face and muse. Indeed, her face has been a canvas for improbable and colourful make-up designs, which reflected the constructivist and futurist roots of punk.

London-based graphic designer Raissa Pardini, who met Jordan during the production of her biography (Defying Gravity, Omnibus Press), remembers her fondly: “I was wearing a leather beret, a vinyl jacket and a Modern Lovers t-shirt. It was inevitable to start gossiping. She had a unique way of speaking and listening, she knew how to give you space and was interested in everything you said. She encouraged me to start my own business and not take lessons from anybody when it came to art. And so it happened a year later."

Today, her words in the film Jubilee (1978) by Derek Jarman inevitably come to mind: "Make your desires reality. I, myself, prefer the song ‘Don’t dream it, be it’”.

Jordan as Amyl Nitrate perfroms “Rule Britannia” in Derk Jarman’s Jubilee, 1978.

In the film – a crazy and deranged vision catapulting Queen Elizabeth I in the accellerated and nihilist London of the times on the occasion of the 1977 Silver Jubilee (also the subject of Sex Pistols' outrageous river Thames boat party) – Jordan, in the role of Amyl Nitrate, plays a fluorescent green fishnets-wearing Boadicea who proudly sings a camp and syncopated version, between reggae and the Clash, of “Rule Britannia”.

Suspended between a cup of tea, milk-no-sugar, and an electric guitar, between the monarchy and figures like Jordan Mooney, this is the United Kingdom made of a pastiche of visionary subversions and deconstruction of its patriotic shrines that so much has given – and still does – to art and to pop culture.

With the long-awaited Sex Pistols TV series directed by Danny Boyle (Trainspotting) on the way, one has to hope that the celebration of Jordan's work and figure can represent the opportunity for a new generation to rediscover punk. Something now needed as never before, in a society where the constant obsession with pre-ordering (from museum tickets to restaurant seats) and tracking has castrated all forms of spontaneity, artistic and social.

Opening image: Jordan’s constructivist make-up in a scene of Jubilee, Derek Jarman, 1978. Photo frame from film

A prize for architecture between lights and volumes: LFA Award

An international photography competition that invites photographers worldwide to capture the essence of contemporary architecture. Inspired by the work of the famous Portuguese photographer Luis Ferreira Alves, the award seeks images that explore the dialogue between man and space.