In April 1983, journalist, lecturer and art critic Francesca Alinovi ventured on the dancefloors of a series of discos in the Italian region of Emilia Romagna, explaining their relationship with design for Domus 638.

Among these featured Kinki, a Bolognese club that Alinovi, a foresighted observer of the international underground on the Bologna-New York axis, narrated from the perspective of its interiors. An undoubtedly unprecedented and visionary approach to the storytelling of clubbing for the time. One that Domus had already undertaken since the 1960s and which would later be shared by Fulvio Ferrari in his essay Disco 1968 – L’Architettura Extraordinaria (Galleria, 1989).

The venue’s interiors designed by Fabrizio Passarella and Giovanni Margotto boasted neon lights shielded by resin surfaces combined with erotic frescoes, fountains and props for old sword-and-sandal films dismissed by Cinecittà. According to Alinovi, Kinki hence presented itself “in a luxuriant Pompeian style” with an environment “made for thrill as well as Olympian calm”.

Only a few years had passed from the reportage, when Micaela Zanni, a teenager at the time, entered Kinki for the first time and never left it since. Over the years she went from being a PR to co-owning the club, overseeing its artistic direction until a few weeks ago.

The opportunity to discuss the venue and its second-to-none legacy, though, comes with its unexpected closure. The responsibilities are not to be found in the prolonged Covid-induced stop, but in the collapse of the building’s attic which occurred two years ago following works on the building. The consequent negligence of the institutions, then, did the rest. As Micaela now complains, Kinki, despite its historic value, wasn’t seen as an opportunity for the city of Bologna, but as “something to be badly tolerated, as we have witnessed during the pandemic”.

From the Beats to the student contestation

Yet the venue, for over fifty years, has been a landmark of Bologna and of its youth culture. The club was founded in 1958 under the city’s iconic two towers with the name of Whisky a Go Go, inspired by the successful Parisian venue of the same name.

However, it was Los Angeles Whiskey a Go Go to inspire its art direction which, thanks to the promoter Beppe Brilli, made the club a mecca for the burgeoning Beat phenomenon. On its stage the cream of Italian underground music performed, including the likes of Lucio Dalla, Equipe 84, I Judas, Mal & I Primitives, I Casuals and, as legend has it, also Jimi Hendrix. The guitar virtuoso found himself playing there (albeit some claim it was at the Stork Club) in 1968, when after his gig at the city’s Palazzo dello Sport he went to the Whisky for a jam, which culminated in a midnight spaghetti meal. The venue, on top of its music, was in fact also well-known as a spot for the so-called “biassanot”, the bolognese night owls.

After a brief phase as Whisky Club, the place was renamed Champagne Club first and then, in the 1970s, Pubsi, becoming the place where, during the years of the youth contestation “the students who skipped their classes met”, says Zanni.

The first queer club in Italy

In 1975 the transition to Kinki Club and to its “man only” policy happened, making the club the first queer venue in Italy. DJs alternated with performances by artists who contributed to affirming the sound and aesthetics of the Italian queer avant-garde: Loredana Bertè, Cristiano Malgioglio and the androgynous Amanda Lear.

True to the adjective that inspired its name – ‘kinky’ reads “sexual behaviour that most people would consider odd or unusual” in the Oxford English dictionary – the club was responsible for a new interpretation of the evironment of the disco. A theater of experimentation and transgression, not only musical and artistic, but also sexual and stylistic. A role that in the same years was shared by very few other clubs in Italy, like Easy Going in Rome and, only in a second time, Plastic in Milan.

Neverland

“When I entered Kinki for the first time, in 1986, I didn’t fall in love with the environment but the music. You would not hear it anywhere else in Italy, except for the Palladium in Vicenza or on American radio stations”.

Only three years have passed since the Domus article by Francesca Alinovi and the Kinki recalled Micaela was a totally renovated place. A few months earlier, the opening in the city of a new club with a dark room marked the migration of the Kinki clientele, marking the end of its exclusively homosexual door policy. In an attempt to revive its fate, an Australian salesman from the Nannucci record store took the reins of the decks.

“At Kinki there were always two queues: one of those who hoped to get in, one – across the road – of people who would gather to watch these strange, crazy people who entered the club”, says with a subtle Emilian accent Zanni, whose words capture as vivid snapshots the pivotal role that the club has played not only for music, but above all for costume and design in Italy.

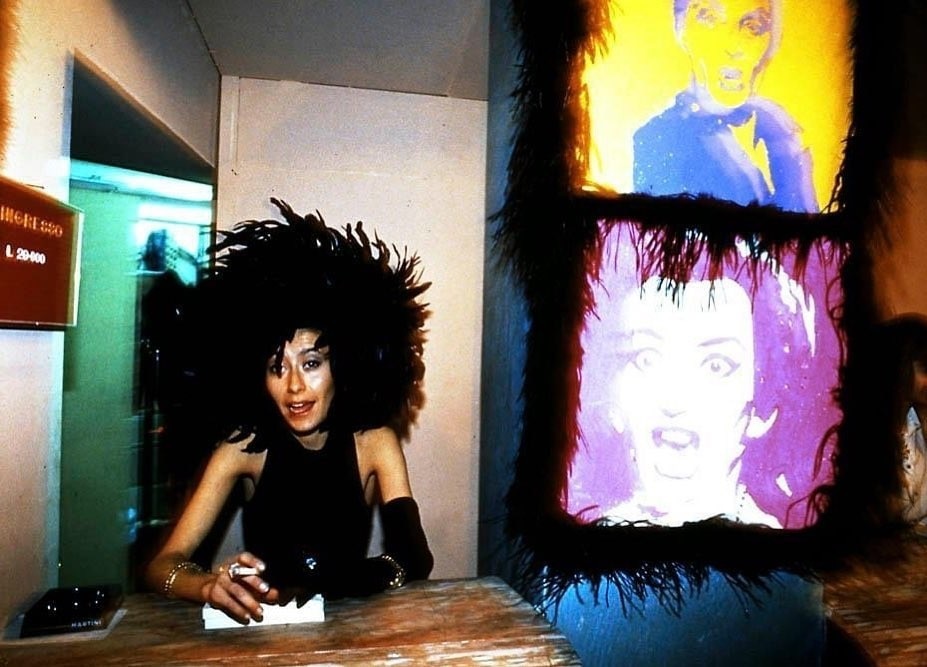

There is a photograph of Micaela – which in April 1990 even ended up on the cover of Discotec magazine, “the Vogue of discos” – sitting on a ladder, her face wrapped in a black feather boa in guise of a clubber Audrey Hepburn. An otherworldly shot that justifies the words of the art director: “Kinki was my Neverland. All those people who didn't have a home during the day found it there. Especially the transsexuals, because nobody wanted them at the time.”

Bologna like New York

In those years Bologna was going through an unparalleled season of social change and creativity, the culmination of an artistic zeitgeist that saw the city become an open-air laboratory of post-‘77 Italy. It was home to the collective squathouse Traumafabrik, to the raw and hallucinated comics of Andrea Pazienza, and to the impossible hairstyles of Orea Malià. The city, though, was also a hub where the New York street art avant-garde introduced by Francesca Alinovi flirted with the No Wave sound of Italian Records, while on the riviera the clubs pulsated to the beat of Italo Disco. Two books capture the disillusionment mixed with the neon-lit hedonism of this new generation: A Post-Modern Weekend by Pier Vittorio Tondelli – where Kinki is mentioned – and Fluo by Isabella Santacroce, on whose cover one can spot Micaela herself posing as part of a group of girls with sonic outfits.

“New York had nothing on Bologna. Despite having a fervid underground scene, NY still had a lot of disease and degradation compared to here”, says Zanni.

To understand Micaela’s words, it would be sufficient to think that Kinki, as early as the 1980s, had an X bathroom. A gender neutral toilet that was forced to close by the 1990s bureaucracy, despite its proclaims of inclusion.

The laboratory of international design

The spirit of hedonistic ecstasy which defined Kinki’s past and present was fundamental in turning the club into a runway, where designers flocked to observe dancers and get inspired for their new creations.

“The protagonists of the homosexual phase of the club were the actors of its explosion of colours. There were people all over the top, different from each other, VIPs and ordinary guys, but they all interacted and mixed perfectly. Now you would call it culture, but at the time it was simply the norm”, explains Zanni. According to her, Kinki represented for Bologna that stage of sexual and aesthetic freedom that, at the beginning of the decade, Blitz – the springboard for the artistic future of the English capital and of personalities such as Boy George – had been for London.

If Mick Jagger, no longer considered to incarnate the spirit of the times, wasn’t allowed inside the Blitz Club, stars of the caliber of Mick Hucknall of Simply Red fame or Rupert Everett could be refused entrance to Kinki.

“Just think that in those years Matt Dillon had moved to Bologna, the guys from Studio Zeta came especially from Milan for Kinki. Not to mention all the people who came from Rome for the male clerks of the Emporio Armani store, the first in Italy, which the manager personally and carefully selected,” laughs Micaela.

What is left of clubbing in Italy?

“In times of mass spectacle, special attention is paid to places where individual spectacle is measured,” wrote Francesca Alinovi, questioning the phenomenon of discotheques in Italy on Domus 638. Almost forty years on, in times of spectacle of the digital self it seems oxymoronic to observe the dancefloors deserted, unable to attract a generation as enthusiastic about media overexposure as frighteningly reluctant to aggregate in real life.

“Today the search for standardization is so great that the dimensions offered by single clubs are not enough,” explains Zanni. A phenomenon that, according to Kinki’s art director, is a symptom of the resignation of a new generation alienated from the lockdown and from the abuse of technological tools. “There is a lot of progress, but little life. There is no transgression, to be understood as the will to go beyond conventional.”

Thus, while the discos are institutionalized like long-gone loved ones with a series of celebratory projects (the documentary Disco Ruin by Lisa Bosi, the photographic essay Disco Mute by Alessandro Tesei and Davide Calloni), the club disappears as a space of social interaction and, above all, of artistic experimentation. Hand in hand with the collapse of subcultural militancy, the public is therefore unable to become loyal to a club, highlighting how in today’s Italy clubbing survives as an affair for the last romantics of the older generations.

As Micaela recalls, “in the past a club could be hideous, but it was the people, who shone, to make it. Now, a venue may be beautiful but the people are bland, they’re worthless than the wallpaper.”

Opening image: Kinki’s entrance with black asbestos floor. Domus 638, April 1983