While I am tidying up the material in order to remember some of the personalities from the architecture, design and art world who have left us in this 2020 – John Baldessari, Adolfo Natalini, Yona Friedman, Vittorio Gregotti, Germano Celant, Nanda Vigo, Christo, Milton Glaser, Cini Boeri, Enzo Mari, Lea Vergine – I realise a few characteristics that these people, so important for the design culture, have in common. First of all, their professions are difficult to place in a single definition: architects, designers, graphic designers, artists, critics, perhaps they can simply be described as connoisseurs of the arts and their expressions. All born between the 1930s and 1940s, they experienced the war as children and, as young people, its end and animated the overwhelming impulse to rebuild what followed it. “This life seemed normal, the situation was general, the danger belonged to everyone, not personal, the fact that the drama was collective made everything more acceptable”, Cini Boeri stated, talking about the Milan’s bombing.

The words of the Milanese architect immediately leads to a reflection on the new collective drama we are experiencing, a war without bombs, which touches every inhabitant of the planet, which will be followed, we hope, the same strong creative impulse that has always brought man to react to critical situations and to propose solutions for change.

Secondly, most of this large group met in Milan. These were years of extraordinary fervour, the 1950s, when everything changed. Sometimes Boeri, Mari, Christo, Lea Vergine, Gregotti and Celant would find themselves published together in a Domus’ issue; one would write about the other, promote him/her, criticise him/her, review the exhibition, the book, edit the catalogue or illustrate the cover. They contributed to nourishing the cultural ground of reconstruction, each with a highly personal, disruptive, meditative, provocative approach, capable of astounding the whole world, or a fighter one, unwilling to compromise with trends or with common criteria related to the reality investigation. The hole will be felt.

All born between the 1930s and 1940s, they experienced the war as children and, as young people, its end and animated the overwhelming impulse to rebuild what followed it

What legacies do they leave us? Certainly, enormous and countless tributes, books and exhibitions will trace their brilliant professional activities. Some of them, as Vittorio Gregotti, chose donating their archives to Milan; Enzo Mari did the same, but he wanted to make them accessible in forty years, when there will be a generation “capable of making conscious use of them”. On the other hand, Yona Friedman left us a simple website with his works, so that his ideas and visions can inspire the younger generation.

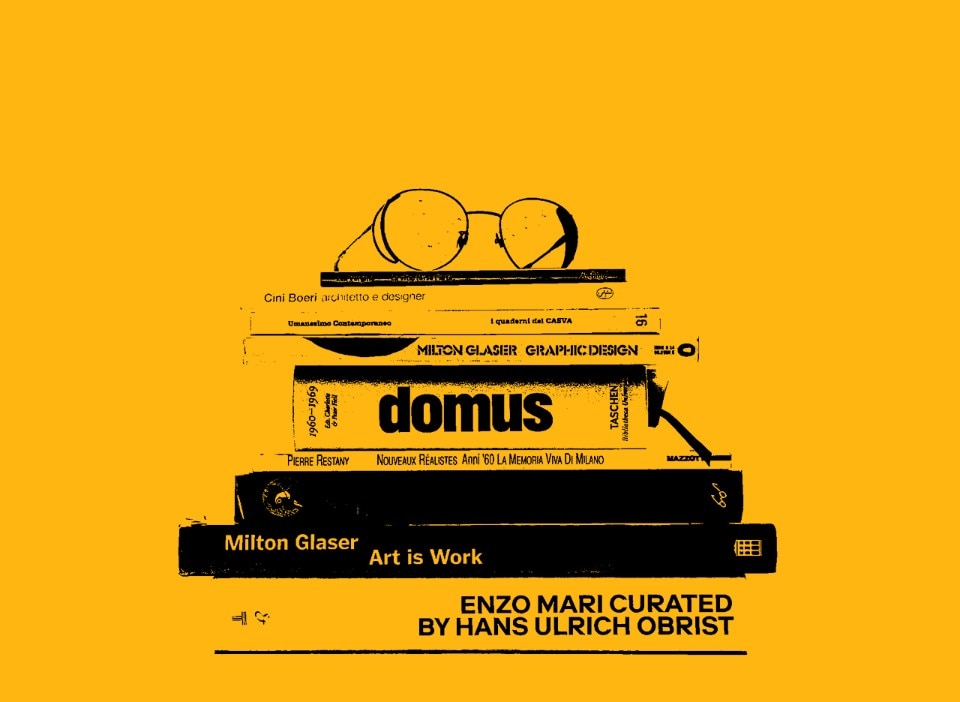

For each of them, we suggest a contribution – an exhibition or a lesser-known project – to look for and discover, or a book that talks about him/her; footprints to approach or enhance the fifty-year history, design and much more animators. Perhaps, some of these objects are already in our homes, in our bookshops, or can be accessed with a simple click.

They contributed to nourishing the cultural ground of reconstruction, each with a highly personal, disruptive, meditative, provocative approach, capable of astounding the whole world, or a fighter one, unwilling to compromise with trends or with common criteria related to the reality investigation. The hole will be felt

John Baldessari (National City, California, 1931)

A Californian architect and artist, since the 1970s he reflected on the art language, both written and visual, and on the strength of images and their associative power. In the 1970s he announced to the world that he was burning all his works produced from 1953 to 1966 and putting them in an urn, in an act of art cremation, subjected to a life-cycle as well. His works draw on the iconographic collection produced by mass culture: he integrates photographs and pictorial interventions in an ironic deconstructive game that questions the very concept of conceptual art. In 2010, the London’s Tate Modern and Los Angeles’ LACMA hosted an exhibition on his work.

An episode not to be missed: a young Marge Simpson interviews John Baldessari about his choice to paint giant mouths and noses.

A conversation to listen to again: on the Tate Modern’s website, Baldessari talks about his work on the occasion of the Pure Beauty exhibition, curated by J. Organ, L. Jones, in 2009.

Adolfo Natalini (Pistoia, 1941)

Architect and lecturer, he grew up in the 1960s’ Florence and traced the radical architecture path, founding Superstudio with a group of friends. Abandoned functionalism, the group designed imaginary architecture, imaginative large-scale installations, where there was no distinction between art and architecture. At the University of Florence, he conducted research into material urban culture, and encouraged his students, including the young Michele De Lucchi, to collect and design the heritage of rural cultures. He bequeathed to his students the drawing practice as a daily exercise, which he entrusted to private notebooks pages. Natalini took an independent professional path, with the Natalini Architetti studio, but throughout his life he continued “secretly” to be a painter (see Portfolio, in Domus 1027, 2018).

A book to look for: A. Natalini, L. Netti, A. Poli, C. Toraldo di Francia, Extra-Urban Material Culture, Alinea edizioni, 1982.

An exhibition to visit virtually: Super Superstudio, curated by Andreas Angelidakis, Vittorio Pizzigoni, Valter Scelsi, at PAC in Milan, 2015-2016. Accessible on the museum’s website, with a wide photo gallery.

Yona Friedman (Budapest, 1923)

French architect and theorist of Hungarian origin. In Paris since 1957, his research is directed towards urbanism and the possibility of adapting cities to contemporary needs; he proposed elevated megastructures in order to manage urban traffic and preserve the countryside and the historic city. In 2017, he published Roofs, a collection of practical information on the construction of shelters using waste materials to meet the material needs of poor countries: through self-design, architecture can be the tool that allows people to actively participate in the creation of social life. Friedman’s Paris home is a magical full of books, drawings and waste objects treasure chest transformed into small works of art, telling the story of the architect, the man and his poetics of “recovery”. His paper file was acquired by the Los Angeles’ Getty Center.

A website to discover: on the architect’s personal website, you are greeted by the phrase “Yona Friedman wishes to inspire young(er) people with ideas and views”.

A book to read: Y. Friedman, L’Ordre compliqué et autres fragments, Quodilbet, 2008.

Vittorio Gregotti (Novara, 1927)

Architect, urban planner and architectural theorist, he trained as an architect and an intellectual in Milan under Ernesto Nathan Rogers and around the editorial Casabella’s staff, which he assumed the supervision of from 1982 to 1996. In the 1960s he worked on projects on a territorial level, respecting the contextual characteristics of the place, and in 1975 he was director of the Venice Biennale. Since 1985, he had been working on the transformation of the Bicocca Pirelli’s district in Milan, and in 2002 he completed the Arcimboldi Theatre. The archive of his professional activity was donated to Milan in 2013 and is currently kept at CASVA, Centro Studi Arti Visive, at Castello Sforzesco.

A book to read: to start learning about the Gregotti, Meneghetti, Stoppino and Gregotti Associati’s archives: Umanesimo contemporaneo, edited by Teresa Feraboli, Quaderni del CASVA 16, 2016.

A project worth visiting: The Belém Cultural Centre, Lisbon (1988-1993), designed with the Portuguese architect Manuel Salgado.

Germano Celant (Genova, 1940)

An art critic, curator, and art director, Celant moved around Genoa in the 1960s, where he began to be interested in artists who worked with art in different ways, which he brought together in the definition of “Arte Povera”. He investigated, defined and promoted, in the United States as well, artistic expressions that address contemporary culture, such as Conceptual and Land Art, architecture, design and photography; he followed artists and curated their exhibitions and their huge catalogues. Travelling between Milan and New York, he was interested in the dialogue between art and architecture and in museums. In 2016, he curated Christo’s art installation at Lake Iseo. He was the curator of the New York’s Guggenheim and the Fondazione Aldo Rossi, Fondazione Vedova’s artistic director and collaborator of the Guggenheim in Bilbao.

An exhibition to look to again: the first major retrospective of Janis Kounellis’ work, at the Fondazione Prada, in 2019. The rooms of the Venetian Ca’ Corner della Regina’s Palace will host some of the famous Greek artist installations (Piraeus 1936 - Rome2017). Celant curated the catalogue: G. Celant, Kounellis, Progetto Prada Arte 2019.

A book to read: G. Celant, Christo and Jeanne Claude. Water projects, Silvana Editoriale 2016.

Christo (Gabrovo, 1935)

Christo Javacheff was born in Bulgaria and led a difficult life until his arrival in Paris at the end of the 1950s. Here, he joined the Nouveau Réalisme movement, with the artists Arman and Yves Klein, supported and promoted in Italy in the Domus’s pages by the critic Pierre Restany. Along with his partner Jeanne Claude, Christo created an artistic partnership, in which the aim was to reverse the meaning of the relationship between the work and its context: the couple packed two kilometres of Australian coastline (1969), Vittorio Emanuele’s Statue in Piazza Duomo in Milan (1970) and the Pont Neuf in Paris (1985). Large-scale art installations, self-financed through the sale of preparatory work, drawings and sketches, such as The Floating Piers (2016), $18 million invested to set up more than four kilometres of floating walkway, which brought more than a million visitors to Lake Iseo.

A cover to discover: Domus 704, April 1989, with a drawing of thousands of yellow umbrellas installed simultaneously in Ibaraki, Japan, and in Los Angeles.

A catalogue to be recovered: published on the occasion of the exhibition at the Fonte d'Abisso Gallery, P. Restany, Nouveaux Réalistes Anni '60. La memoria viva di Milano, Mazzotta 1997.

Nanda Vigo (Milano, 1936)

Artist and designer, she studied at Lausanne but fully breathed the 1950s’ Milan atmosphere, beside Lucio Fontana, her partner Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani. She fluently moved among art, design and architecture: in her productions and private houses, she focused on her research about the space construction through light, as a 1964’s Milanese flat, “astonished” as Cesare Casati described, who wrote on Domus, “it is beautiful that a work like this was born in Milan, the ‘Art Nouveau’s cradle’, and that it is now a young woman – while men are lost in embroidery with precious designs, old and new forms – who redeems the ‘Milanese taste’ with a stroke”. She worked in Milan, but was constantly travelling to Africa and the East, curious about ancient civilisations.

A cover to discover: Domus 482 of January 1970: on its cover, the home for the collector Meneguzzo in Malo, near Vicenza, where art is totally incorporated in the domestic spaces.

An exhibition to visit: Nanda Vigo - Private Collection, curated by Andrea Dall’Asta SJ, at Museo San Fedele in Milan, inaugurated in October 2020 (and closed, waiting to visit it); it collects designer’s works donated to the Milanese museum.

Milton Glaser (The Bronx, New York, 1929)

The graphic artist par excellence, the one who you underline twice, in red, in the 20th century art dictionary. His strong-coloured drawings, his defined outlines and his soft lines synthesise a set of passions and artistic references: comics, Art Nouveau, oriental art and the Italian Renaissance, which he was able to deeply explore during his travels, such as to Bologna, where he attended Giorgio Morandi’s lectures. Some brilliant works, such as the I Love New York logo, and the Bob Dylan’s album cover with its soft and colourful locks, appointed his worldwide fame. The advertising campaign for Olivetti with the typewriter designed by Ettore Sottsass put the cherry, as red as the Valentine, on the happy results of Italian design in those years. Naturally, he was awarded the Career Compasso d'Oro Award in 2018.

An object to discover: The Noldo and Foldo’s sunglasses, designed by the master at the age of 88, in a limited edition, for Classic Specs.

Two books to have: M. Glaser, Art is Work. First published in 2000, the Italian version is by Electa, 2003. Glaser retraces his work and describes the contemporary scenario; In The Push Pin Graphic: A Quarter Century of Innovative Design and Illustration, we discover the work of the legendary graphic and illustrator studio Push Pin. Two books recommended to me by Giuseppe Basile, Art Director of Domus and a great admirer of Glaser.

Cini Boeri (Milano, 1924)

Maria Cristina Mariani Dameno, better known as Cini. She studied in the Gio Ponti and Marco Zanuso’s Milan, whom she trained and collaborated with. The architect distinguished herself by researching the functionality of the project and the production efficiency before aesthetics. Her modular Strips sofa for Artflex won the Compasso d'Oro Award in 1979. In civil architecture, she concentrated on the distribution of space, on the autonomy and the inhabitant’s freedom in the domestic dimension. Lea Vergine wrote of her “poetic dimension of openness about being and existence which Boeri never shies away from, the passionate reflection on the ideas of the western avant-garde, careful to the so-called industrial civilisation, but nevertheless linked to ethical and political commitment, knowing how to link invention, deduction and the production world. Another peculiarity is that the architect has never omitted love in her architecture. The architecture of emotions and feelings... Can we say that? Why not”.

A project to know: The private homes Casa Quadrata and Casa Rotonda on La Maddalena’s island, Sardinia

A book to read: Cini Boeri. Architetto e designer, edited by Cecilia Avogadro, Silvana Editoriale 2004. It is the first catalogue raisonné on her work, with a long and accurate interview.

Enzo Mari (Novara, 1932)

Artist, designer, lecturer and theorist. Five Compasso d'Oro Awards, including one in 1967 for his “individual research on design”. Perpetually fighting to defend the ethics of design as a reasoned act that does not adapt to trends, his name immediately brings to mind the silk-screen prints of the apple, the pear and the goose. However, Mari ranged from the Programmed Art to the industrial design, exhibition design and editorial graphics, as documented by the exhibition that recently opened (and closed) at the Milano Triennale. For the “object publishers” Bruno Danese and Jacqueline Vodoz, he designed beautiful and refined pieces. Everyone remembers his fighter nature and his rigorous design. He loved growing bonsai trees on his terrace.

A project to be rediscovered: the Agenda Olivetti, which he designed the graphic project for, in a simple and immediate style.

A book to compose: Life: A User’s Manual by G. Perec in the version designed by Mari in 2009: each chapter is a piece of a puzzle. A book to read and reassemble.

Lea Vergine (Napoli, 1936)

To the registry, Lea Buoncristiano. An art critic and curator, she was acute and determined, at a time when art, as architecture, was a men’s prerogative. She investigated contemporary artistic expressions and their relations with literature, starting from the 1960s’ Naples of the informal art and arriving “riding or coasting along Body Art and Land Art, Camp and Trash, to the most recent Milanese sadness”, in Giovanni Agosti’s words, art historian and Lea Vergine’s friend. She moved to Milan – “the descent to the North”, as she called it – to live with her partner Enzo Mari, introduced to her by Giulio Carlo Argan, in 1968: in the memories of those who frequented them, or who “invited themselves” to their Milanese home, Lea and Enzo were the “most beautiful and most feared” couple in Milan.

An exhibition to be rediscovered: The Other Half of Avant-garde 1910-1940. Painters and sculptors in the movements of historical avant-garde at the Palazzo Reale in 1980. Lea Vergine investigated the women artists’ contribution, condemned to oblivion by art critics, within the history of contemporary art, in the beautiful setting entrusted to Achille Castiglioni, who cut the space with stretched white sheets, simulating the artists’ attics or studios and creating a more intimate dialogue with the works.

A book and an article to read: L. Vergine, La vita, forse l'arte, Archinto 2014. The booklet collects her writings from 2000 to 2013. On the cover, an Enzo Mari’s drawing, and a Giovanni Agosti’s preface, whose beautiful memoir Enzo e Lea. Filemone e Bauci a Milano, published on Alias on 1 November 2020.