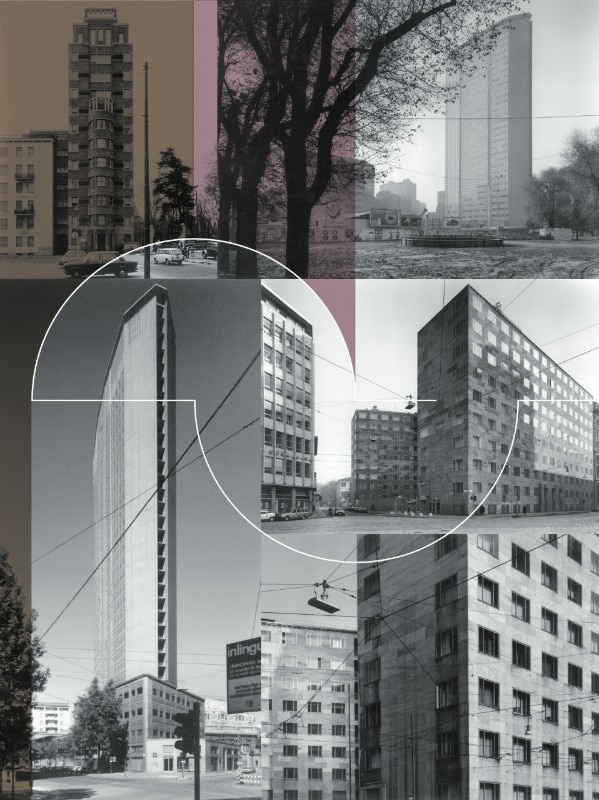

Rasini tower, Pirelli tower and the first Palazzo Montecatini photographed by Gabriele Basilico in the 1980s

Originally Published on Domus Gio Ponti / 2008

They were the years of “general protest”, when students were for the most part busy with meetings and demos. In that state of affairs, architecture as a design experience was only of secondary interest. People preferred to talk about it from the point of view of social habitats and conditions, while turning out large numbers of “field surveys”, mainly of city suburbs. Paradoxically, when my studies were over, since I had chosen photography for my future, I became more directly involved in architecture.

I started by working to document the work of architects and, more frequently later, for publishers and magazines.This gave me plenty of time to experiment with the different ways in which the works of architects could be interpreted through the lens, and reinterpreted in print media. So it was not just a matter of photography, but also of graphic composition, page layout and hence image. Before acquiring a permanent consolidated language I had been looking very closely at those photographers whom I regarded as my masters, the big names of that time who were all over the Italian magazines: Aldo Ballo, chiefly for his interiors and still-lifes, Giorgio Casali for contemporary architecture, and Paolo Monti for historic architecture and urban landscapes. But also Ugo Mulas and Gianni Berengo Gardin, who were all-round photographers with a knack for capturing architecture with human presences. I had a great admiration for the top inter- national masters: Ezra Stoller and Yukio Futagawa. With Global Architecture – the series of assiduous- ly edited large-format monographs dedicated to single works of architecture – their stereotype was a very seductive formalistic vision and a hyper-aesthetic approach to architectural forms. In 1980 I was invited by the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Bologna to organise, with Italo Zannier and Gaddo Morpugo, an exhibition entitled “Photography and Images of Architecture”. On that occasion I was able to invite – and get to know personally – Giorgio Casali, through the good offices of Marianne Lorenz who was head of the editorial department at Domus. Giorgio Casali had always signed his photos “Casali Domus”. This association between a proven, perspicacious photographer and one of the best-known architectural publications lasted about 30 years. In the course of time, a joint “visual style” was perfected. Under the guidance or influence of Gio Ponti, and with the use of a highly consistent graphic design, it grew steadily more distinctive and unmistakable.

Casali had confided to me that he always worked at a brisk pace, preferring a fully-fledged architectural reportage to a few individual shots. For each report he would set out in his Fiat 1100, assisted by his son Oreste and using a 6x6 reflex in addition to a large optical bench camera. From a square negative, by sacrificing much of the frame, he often produced rectangular pictures. This “re-framing” after the shot was obtained simply with the cutting blade, which produced prints of unpredictable and always different sizes and consequently required a free white space for the magazine layout. For a long time I had imagined that this technique was a hallmark of the “Casali Domus” style, in all probability an aesthetic choice made by Gio Ponti.

In other times, to cut a photograph by altering its original frame would have been looked upon as heresy, an unacceptably violent amputation. Whereas in Domus the end result was never without its fascination and originality: with live, full-spread photos, or narrow, elongated cuts both horizontally and vertically, the frequent use even of greatly enlarged details and images dominated by chiaroscuros. This somewhat theatrical approach was decidedly oriented towards a formalist taste, which widened the aesthetic perception of architecture.

I think that for a long time Domus was thus an authoritative landmark, albeit with a very Italian personal slant. It was a sort of photographic international style and it accompanied the evolution of architectural photography. With the use of full colour and eye-catching black-and- whites in terms of representation, it accomplished the goal of boosting the added value of an architect’s work.This idiom mainly highlights the plastic and formal values of architecture, sacrificing context and giving the architectural works a sense of abstraction and in some cases of timelessness. It must also be said that in the early ’80s another attitude had developed in architectural photo- graphy. In a search for more realistic and less abstract images, the work was described by immersing it in its setting, without hiding or relinquishing context and indeed by hunting for possible relationships. The Casali-Domus association ended with the death of Gio Ponti, thus concluding a long period of “sunny” photography, hard to repeat. The same photographer for more than 30 years, by metabolising the thinking and creativity of a great architect, had recorded a densely coherent story of the adventures of Italian and international architecture after World War II.

Since 1982, under the editorship of Alessandro Mendini and up till the present, no other photographer has worked exclusively for Domus. The alternation of editors over the years has witnessed many collaborations with different photographers. Notwithstanding, in the long term it is important to observe that for Domus photography has always played a lead role in its editorial choices and graphic layout. The pattern set by Gio Ponti and his faithful fellow-traveller Giorgio Casali consolidated a style and constructed a strong, lasting and crystalline model. In the mean- time that heritage has been open to fresh influences and overlappings, including those of artists’ photography.

Gabriele Basilico

Gabriele Basilico, architect and photographer, renewed the image of architecture and the urban environment in the 1980s with his reportages for magazines and institutions. He has been responsable for many exhibitions, including "Gabriele Basilico: From San Francisco to Silicon Valley" at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco.