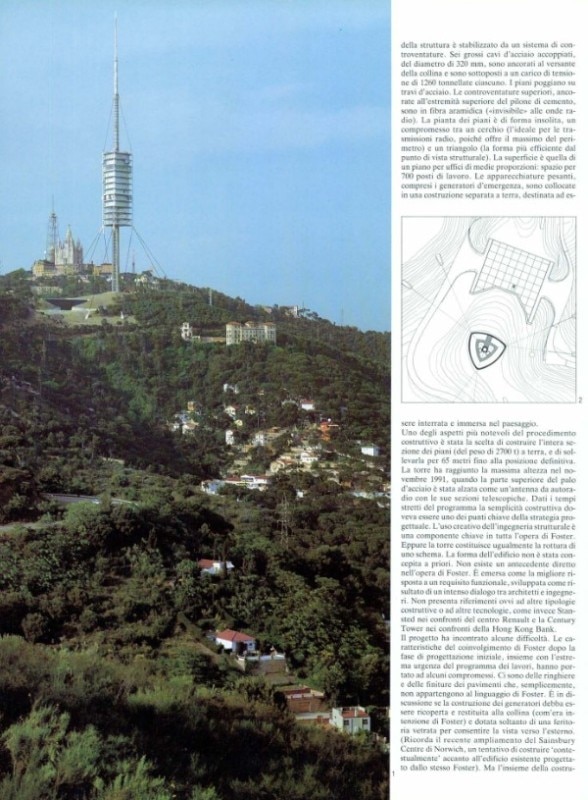

If 2024 Olympic Paris is a city rethinking itself from within by valorizing its own existing heritage, and the 1984 Olympic Los Angeles had been a grand urban-scale project of scenography and visual identity, Olympic Barcelona, growing up in the 1980s in the run-up to 1992, was a case of transformation at a very large scale, based on regeneration of former industrial sites, massive expansion and new construction projects, and major urban landmarks. This was the context to the Collserola tower, signed by Norman Foster, later Domus Guest Editor 2024: telecommunication towers have been a Leitmotif of urban landmark design throughout modernity, but here, in addition to embodying the spirit of an evolving Barcelona burgeoning with innovation and activity, this “pure sculpture,” “minimalist needle,” came to systematize a great complexity of media infrastructure and bring a more harmonious landscape design to the heights embracing the Catalan capital. Manifesta15 has now arrived in 2024 to reinterpret the city with a broader vision, extended to the territory of the entire region and identified in the 3 disused chimneys of Sant Adriá del Besós; the 1992 Olympic season instead brought its multiplicity of spirits together around this symbol, which Domus published in September 1992, on issue 741.

Norman Foster, Telecomunication tower, Barcelona

The tower on the Collserola. recently completed by the British master, represents a further contribution to the dynamic Catalan city and once again demonstrates this architect's constructional wisdom.

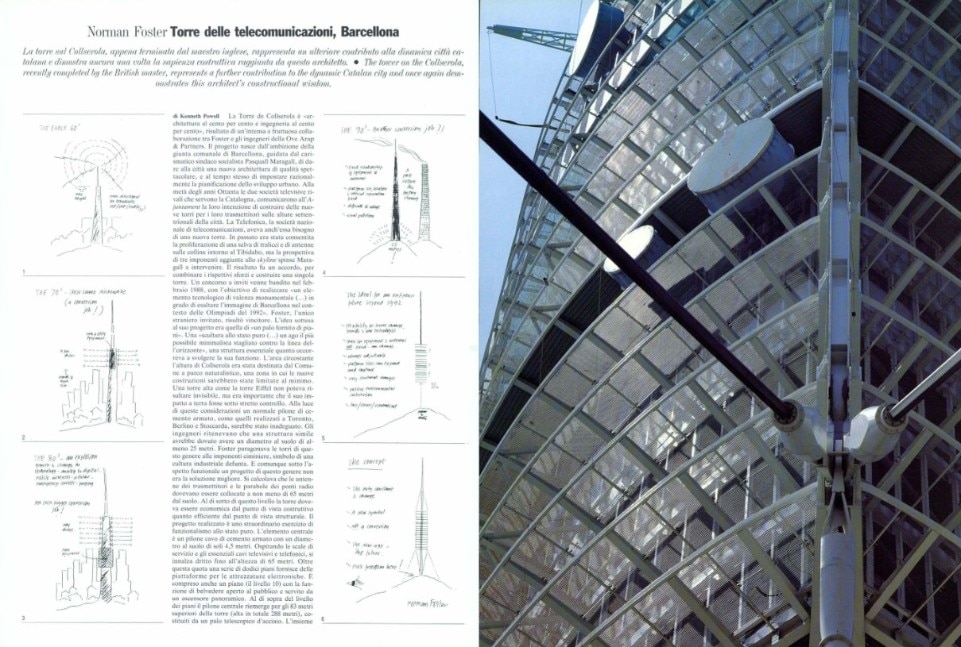

The Collserola Tower is the outcome of an intense and rewarding collaboration between Foster and the engineers Ove Arup & Partners. The project has its origins in the ambitions of the city council of Barcelona, led by the charismatic socialist Mayor Pasquall Maragall, to give the city a new architecture of striking quality and at the same time to impose a rational approach to urban planning. In the mid Eighties, the rival television companies serving Catalunya, told the Ajuntament of their plans to build,new transmitting towers on the high ground north of the city. The national telecommunications company, Telefonica, also needed a new tower. In the past, a straggle of masts and aerials had been allowed to proliferate on the hills around Tibidabo, but the prospect of three very tall additions to the skyline prompted Maragall to intervene. The outcome was a rather reluctant agreement for the three bodies to combine their efforts and build a single tower.

The tower has all the ethereal lightness and apparent impermanence of a temporary structure: the outcome of a ruthless process of paring down, eliminating the extraneous, that is central to Foster’s work.

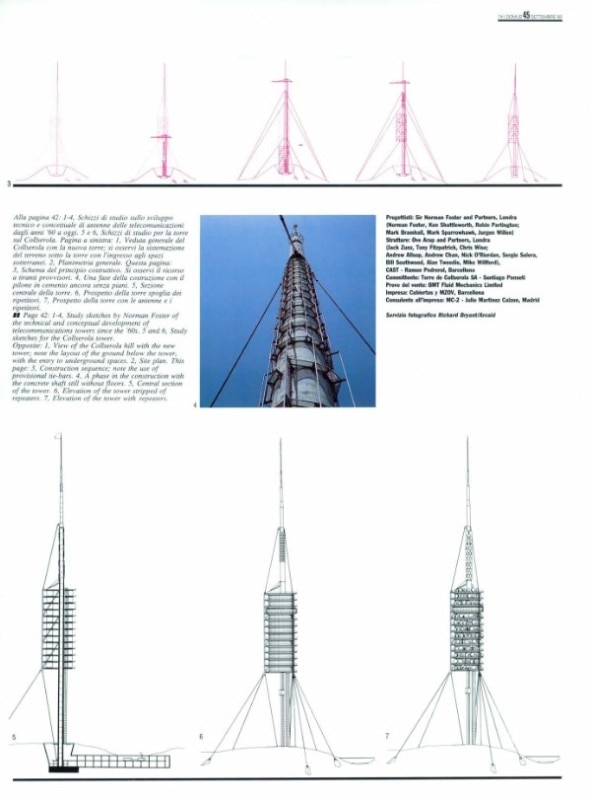

An invited competition was launched in February, 1988, with the aim of producing “a monumental technological element... to enhance the image of Barcelona in the context of the 1992 Olympics” - as well as a key component in the Spanish and European telecommunications systems. Foster, the only non-Spanish architect invited to participate, won the competition. The idea behind his scheme was that of “a stick with shelves”, a “pure sculpture... the most minimal needle on the sensitive skyline”, a structure only as substantial as it needed to be to fulfil its function. The area around the Collserola hill had been designated by the city as a natural park, an area where new development would be kept to the minimum. A tower as tall as the Eiffel Tower in Paris could hardly be made invisible, but it was important that its impact at ground level was strictly controlled. In this light, a conventional reinforced concrete shaft - like those constructed in Toronto, Berlin and Stuttgart - would have been inappropriate. The engineers estimated that such a structure would need to be al least 25 metres in diameter at ground level. Foster compared towers of this kind to huge factory chimneys - symbols of a defunct industrial culture. Functionally, a design of this kind was not, in any case, the best solution.

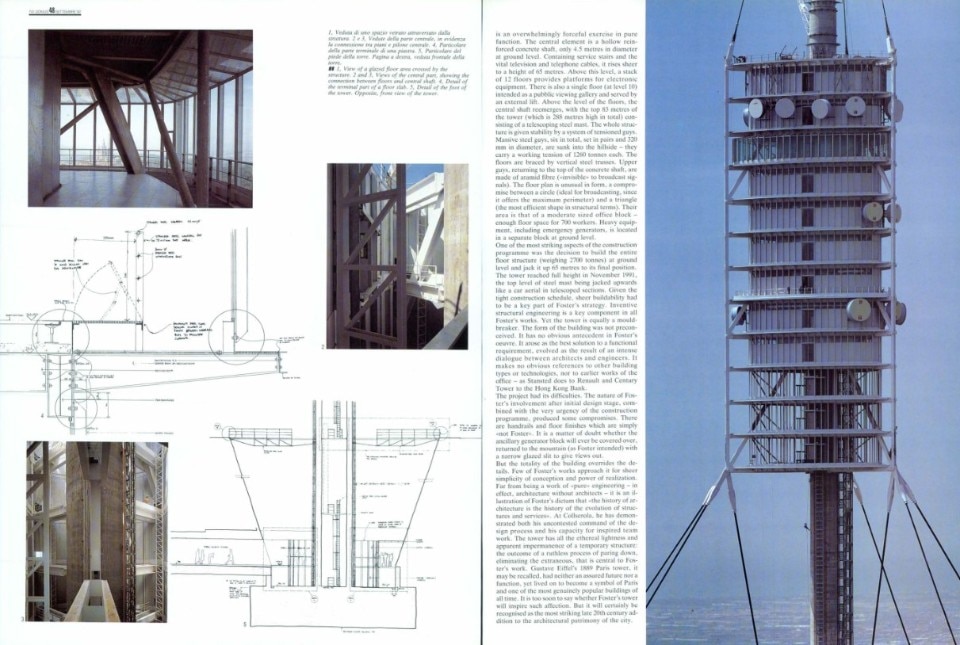

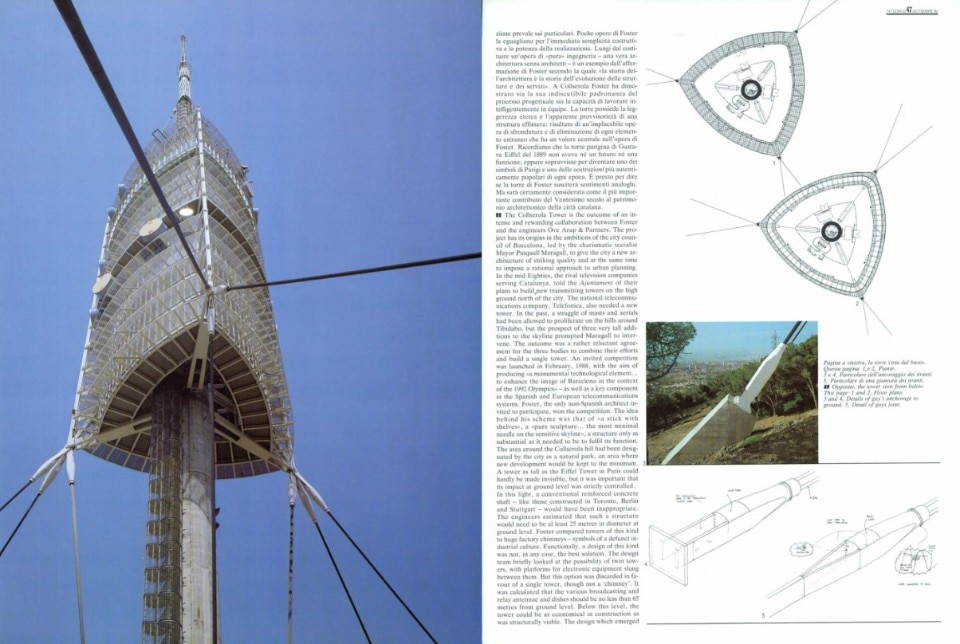

The design team briefly looked at the possibility of twin towers, with platforms for electronic equipment slung between them. But this option was discarded in favour of a single tower, though not a ‘chimney’. It was calculated that the various broadcasting and relay antennae and dishes should be no less than 65 metres from ground level. Below this level, the tower could be as economical in construction as was structurally viable. The design which emerged is an overwhelmingly forceful exercise in pure function. The central element is a hollow reinforced concrete shaft, only 4.5 metres in diameter at ground level. Containing service stairs and the vital television and telephone cables, it rises sheer to a height of 65 metres. Above this level, a stack of 12 floors provides platforms for electronic equipment. There is also a single floor (at level 10) intended as a pubblic viewing gallery and served by an external lift. Above the level of the floors, the central shaft reemerges, with the top 83 metres of the tower (which is 288 metres high in total) consisting of a telescoping steel mast.

The whole structure is given stability by a system of tensioned guys. Massive steel guys, six in total, set in pairs and 320 mm in diameter, are sunk into the hillside - they carry a working tension of 1260 tonnes each. The floors are braced by vertical steel trusses. Upper guys, returning to the top of the concrete shaft, are made of aramid fibre (“invisible” to broadcast signals). The floor plan is unusual in form, a compromise between a circle (ideal for broadcasting, since it offers the maximum perimeter) and a triangle (the most efficient shape in structural terms). Their area is that of a moderate sized office block -

enough floor space for 700 workers. Heavy equipment, including emergency generators, is located in a separate block at ground level.

Far from being a work of ‘pure’ engineering - in effect, architecture without architects - it is an illustration of Foster’s dictum that ‘the history of architecture is the history of the evolution of structures and services’.

One of the most striking aspects of the construction programme was the decision to build the entire floor structure (weighing 2700 tonnes) at ground level and jack it up 65 metres to its final position. The tower reached full height in November 1991, the top level of steel mast being jacked upwards like a car aerial in telescoped sections. Given the tight construction schedule, sheer buildability had to be a key part of Foster’s strategy. Inventive structural engineering is a key component in all Foster’s works. Yet the tower is equally a mould-breaker. The form of the building was not preconceived. It has no obvious antecedent in Foster’s oeuvre. It arose as the best solution to a functional requirement, evolved as the result of an intense dialogue between architects and engineers. It makes no obvious references to other building types or technologies, nor to earlier works of the office - as Stansted does to Renault and Century Tower to the Hong Kong Bank.

The project had its difficulties. The nature of Foster’s involvement after initial design stage, combined with the very urgency of the construction programme, produced some compromises. There are handrails and floor finishes which are simply “not Foster”. It is a matter of doubt whether the ancillary generator block will ever be covered over, returned to the mountain (as Foster intended) with a narrow glazed slit to give Views out.

But the totality of the building overrides the details. Few of Foster’s works approach it for sheer simplicity of conception and power of realization. Far from being a work of “pure” engineering - in effect, architecture without architects - it is an illustration of Foster’s dictum that “the history of architecture is the history of the evolution of structures and services”. At Collserola, he has demonstrated both his uncontested command of the design process and his capacity for inspired team work. The tower has all the ethereal lightness and apparent impermanence of a temporary structure: the outcome of a ruthless process of paring down, eliminating the extraneous, that is central to Fos ter’s work. Gustave Eiffel’s 1889 Paris tower, it may be recalled, had neither an assured future nor a function, yet lived on to become a symbol of Paris and one of the most genuinely popular buildings of all time. It is too soon to say whether Foster’s tower will inspire such affection. But it will certainly be recognised as the most striking late 20th century addition to the architectural patrimony of the city.