The practice of Costantino Nivola – a figure only conveniently definable as a sculptor – has embraced such a complexity of references and inspirations, and such a multiplicity of fields, that it can be said to be close to the Gesamtkunstwerk, to that total work of art that haunted the dreams of much of the 20th century whose history Nivola himself embodied. A sculptor, but also a painter, also a graphic designer, art director at Olivetti from 1937, he then emigrated to New York, shared a long and famous road with the likes of Le Corbusier and Saul Steinberg, and then went on to teach at Harvard Graduate School of Design: his figure is a global figure who always carried the roots of Sardinia where he was born, with its techniques and knowledge. In October 1952, Domus portrayed Nivola while intent on inhabiting his work, in that garden-house on Long Island conceived together with Bernard Rudofsky, amid objects that alone evoked places, true sculpture-paintings-architectures. Issue was 274.

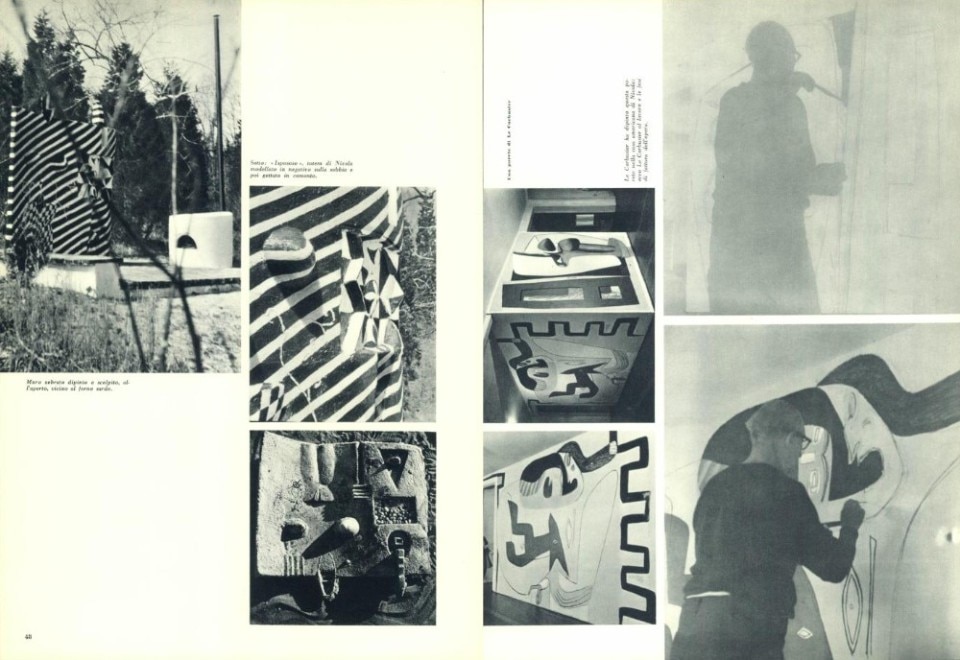

Painted outdoor sculpture, from Domus 274, October 1952

We have already introduced Costantino Nivola to our readers, with some of his sculptures modelled in negative on sand and then cast in concrete, and with a wall in the landscape, a painted wall, an open-air painting palisade (Domus n. 262). There was also mention of his exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York (Domus n. 264-65) and finally of his participation in realizing the Rudofskyan “garden for living” that we presented two issues ago (Domus n. 272). There, Rudofsky and Nivola built and formed by hand, working themselves, the walls of an “open-air room” with a grass and sand floor; Nivola painted the exterior, as he did with the fifth wall that defined the ideal and magical size of a room amidst the greenery.

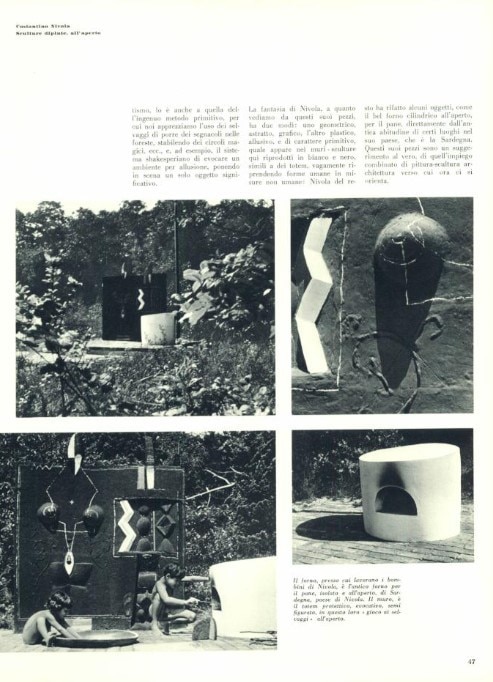

Here we give a broader documentation of Nivola's work and his world: and we can say of his “world” in an almost literal sense, since, as we can clearly see, Nivola and his family are the first to inhabit in the flesh – out of controversy and for fun – the fantastic environment that Nivola establishes when he places one of his walls, sculptures, poles, platforms, in the middle of a natural landscape.

The bewildered object has a proven magical effect, be it the plant inside a room, or the wall of a room in the middle of greenery, in the open air. The effect comes from the unexpected new relationship between the inside and the outside: it is enough to place a contradiction to overturn the value of everything; it is enough to place a real isolated wall, for five other ideal ones to be alluded to, one of which is the sky, whose intervention in the composition is magical enough. It is enough to paint an eye on the back of a hand to create a fantastic animal of it.

Nivola’s imagination, as we see from these pieces of his, has two modes: one is geometric, abstract, graphic, the other is plastic, allusive, and primitive in character, as it appears in the walls-sculptures reproduced here in black and white, similar to totems, vaguely taking human forms in non-human measures: Nivola has in fact remade some objects, such as the beautiful cylindrical outdoor oven, for baking bread, directly from the ancient custom of certain places in his home country, Sardinia. These pieces of his are a real-scale suggestion, of that combined use of painting-sculpture-architecture towards which we are now moving.