The figure of Rafael Moneo, designer and great theorist, is associated with a cultivated approach to architecture, aware of the value of history and context,transversal to ages and resistant to styles, dense with references and interpretations. The long story that saw him win the competition in 1989 for a cultural centre on the site of a pre-existing symbol, a casino, a Kursaal in fact, the identity fulcrum of the resort town on the Basque coast, represents a peculiarity in his career: the consideration of chance as a design tool appears in his methodology, combining with the contrast between abstraction of volumes and the atmosphere envisioned for the interiors. Domus published this milestone of contemporary architecture in March 2000, on issue 853.

Kursaal auditorium and congress center, San Sebastián, Spain

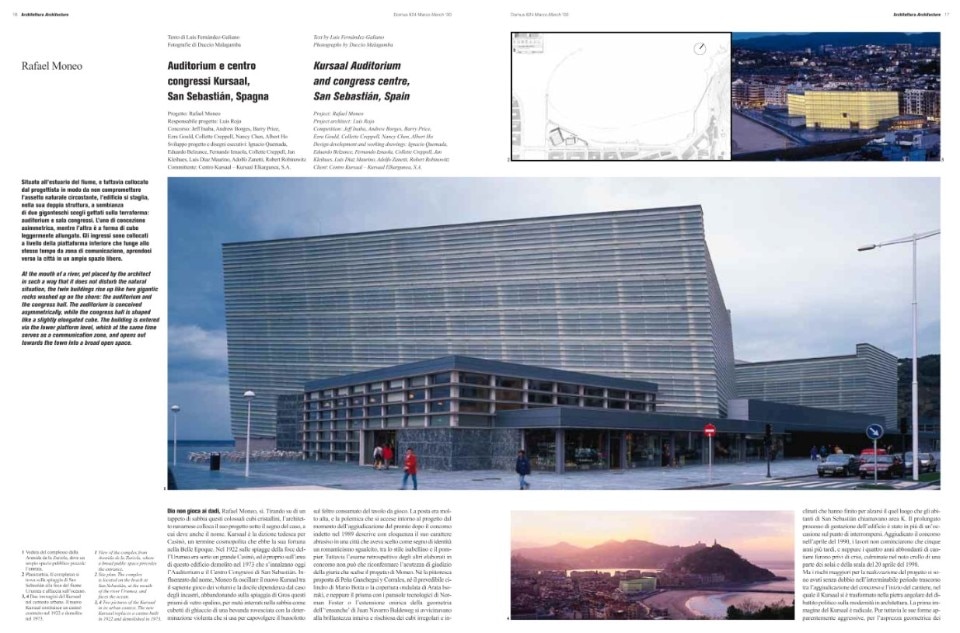

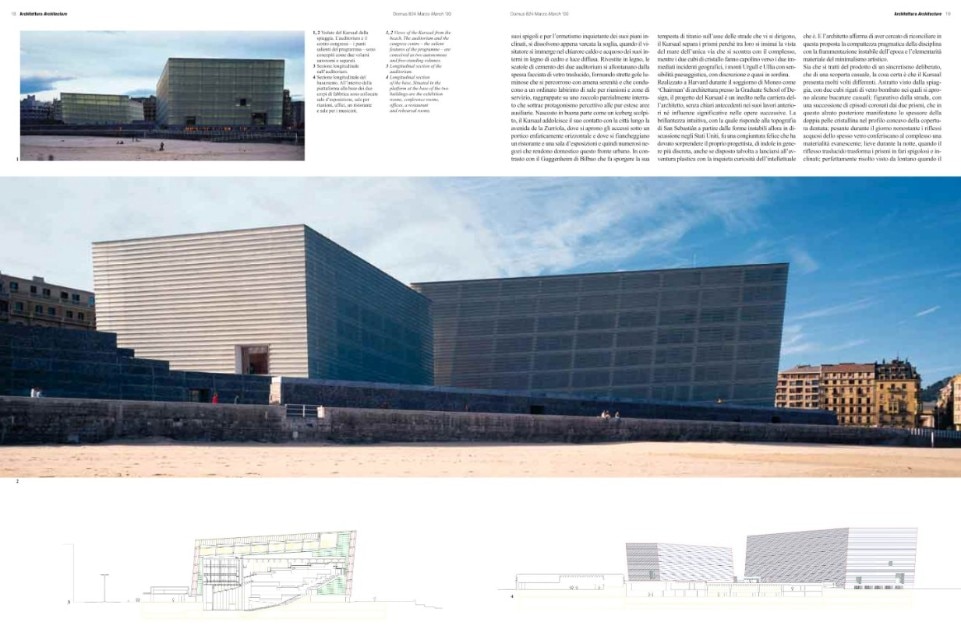

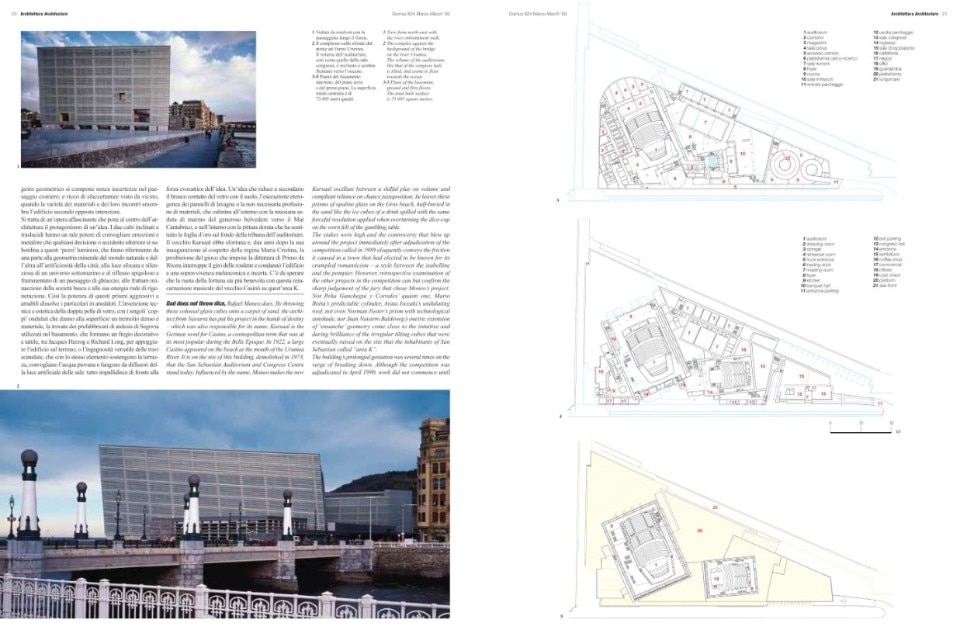

At the mouth of a river, yet placed by the architect in such a way that it does not disturb the natural situation, the twin buildings rise up like two gigantic rocks washed up on the shore: the auditorium and the congress hall. The auditorium is conceived asymmetrically, while the congress hall is shaped like a slightly elongated cube. The building is entered via the lower platform level, which at the same time serves as a communication zone, and opens out towards the town into a broad open space.

God does not throw dice, Rafael Moneo does. By throwing these colossal glass cubes onto a carpet of sand, the architect from Navarra has put his project in the hands of destiny – which was also responsible for its name. Kursaal is the German word for Casino, a cosmopolitan term that was at its most popular during the Belle Epoque. In 1922, a large Casino appeared on the beach at the mouth of the Urumea River. It is on the site of this building, demolished in 1973, that the San Sebastián Auditorium and Congress Centre stand today. Influenced by the name, Moneo makes the new Kursaal oscillate between a skilful play on volume and compliant reliance on chance juxtaposition; he leaves these prisms of opaline glass on the Gros beach, half-buried in the sand like the ice cubes of a drink spilled with the same forceful resolution applied when overturning the dice-cup on the worn felt of the gambling table.

The stakes were high and the controversy that blew up around the project immediately after adjudication of the competition called in 1989 eloquently conveys the friction it caused in a town that had elected to be known for its crumpled romanticism – a style between the isabelline and the pompier. However, retrospective examination of the other projects in the competition can but confirm the sharp judgement of the jury that chose Moneo’s project.

Not Peña Ganchegui y Corrales’ quaint one, Mario Botta’s predictable cylinder, Arata Isozaki’s undulating roof, not even Norman Foster’s prism with technological sunshade, nor Juan Navarro Baldeweg’s oneiric extension of ‘ensanche’ geometry come close to the intuitive and daring brilliance of the irregular tilting cubes that were eventually raised on the site that the inhabitants of San Sebastian called “area K”.

The building’s prolonged gestation was several times on the verge of breaking down. Although the competition was adjudicated in April 1990, work did not commence until five years later; nor were the four years and more spent on the construction site lacking in interruptions and crises, which culminated in the collapse of part of the floors and staircase on 20th April 1998.

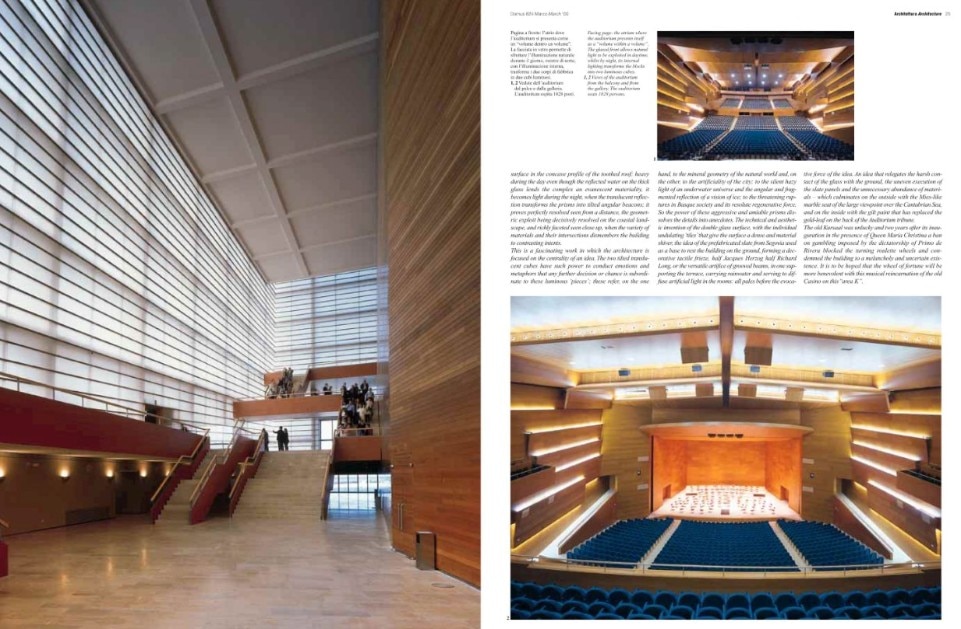

However, the principal danger to completion of the project lay, most certainly, in the interminable period that passed between adjudication of the competition and the commencement of construction works. During this time the Kursaal became the cornerstone of the political debate on modern architecture. The first image of the Kursaal is radical. Nonetheless, its apparently aggressive forms, the harsh geometry of its corners and the unsettling inscrutability of its tilted planes all dissolve as soon as the threshold is crossed and visitors are immersed in the warm, watery glow of its cedar wood interiors and diffused lighting. Covered with wood, the concrete boxes of the two auditoriums distance themselves from the thick facade of translucent glass, forming bright narrow ravines that are travelled with welcome tranquillity and lead to an orderly maze of meeting rooms and service areas. These are grouped in a partially interred plinth that draws perceptive attention to the extensive auxiliary areas.

Much of it hidden like a sculpted iceberg, the Kursaal comes softly into contact with the city along Avenida de la Zurriola, where the entrances open under an emphatically horizontal portico, flanked by a restaurant and exhibition hall as well as numerous shops that lend domesticity to this urban front. In contrast with Bilbao’s Guggenheim, which projects its storm of titanium onto the axis of the streets on its approach, the Kursaal separates the prisms, so that a view of the sea slips between them on the only street that encounters the complex, the two crystal cubes peeking out towards the two immediate geographical points, mounts Urgull and Ullia with scenic sensitivity, discretion and almost with stealth.

Developed at Harvard during the period of Moneo as ‘Chairman’ of architecture at the Graduate School of Design, the Kursaal project is something totally new in architect’s career, having no obvious precedents in his previous works or significant influence on his later ones. The intuitive brilliance with which he responds to the topography of San Sebastián, starting from the unstable forms under discussion at the time in the United States, was a happy combination that must have surprised even the designer, who is generally of a more discreet character, although sometimes willing to throw himself into the plastic adventure with the restless curiosity of the intellectual that he is.The architect says that in this proposal he strove to reconcile the pragmatic solidity of the discipline with the unsettled fragmentation of the period and the material simplicity of artistic minimalism.