In the now well advanced years of the third millennium, the “Poulsen lamp” is that object which only needs to be named for its image to be evoked – icons, when they are icons, work that way – and which is almost automatically placed in interior renderings to determine an atmosphere. A privilege, the latter, sometimes a curse, reserved for a few objects that become design milestones.

In fact, like the objects and furnishings of Alvar Aalto and Arne Jacobsen, PH lamps are now milestones of Scandinavian design, but even thirty years ago their history as well as their creator’s, Poul Henningsen, was little known, despite their widespread use from the earliest days, even in important projects such as Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat. A century-old story that grew out of a modern vision, out of an ongoing progress – the spread of electric light – to which design responses had to be given to allow its integration into the domestic landscape: a story that Domus told in December 1995, on issue 777.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Poul Henningsen, Modern light fitting

There is surely no phenomenon in the history of modern lighting to which so little attention has been paid as the PH lamp. Over the last seventy years PH has become an abbreviation for a type of light known throughout the world, yet the actual inventor is never mentioned by name. In the world of modern architecture the abbreviation suffices and the PH lights were found as anonymous standard fittings in countless modern interiors, in the works of Aalto, Salvisberg, Lauterbach, Mies van der Rohe, Bruno Taut and Ferdinand Kramer. This type of lamp was considered the epitome of modern Danish design, yet it was often difficult to date exactly. An important technical note: the development of the PH lamp went hand in hand with the development of the light bulb.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Poul Henningsen, born in 1894 in Copenhagen, was an architect and even in the early years of life he mixed with progressive Danish writers, musicians and artists. As a young architect, without qualifications since he had not taken his final examinations at the technical college, he soon became known for his critical articles on architecture as editor of the art journal Klingen and later of the Kritisk Revy. He started his professional career in the office of Kay Fisker and then went on to work as a freelance architect. At the beginning of the 1920s he turned his attention to interior design, in which electric light was an important design element.

His first projects still used the newform of light in the classical way. The light fittings were still closely connected to the idea of burning light, either gaslight or candlelight. Not until the designs for the Carlsberg brewery did he break away from the glass prism as a light-scattering device, creating tulip-shaped glass lampshades which can radiate the light directly and diffusely. For the artists’ exhibition in autumn 1921 he worked in conjunction with the artist Axel Salto to create a severely geometrical room lit by dustproof ceiling lights and a central spherical lamp. The lamp itself was the first attempt to use horizontal shades of chased copper to conceal the light source and to use reflection to scatter warm light throughout the room.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Poul Henningsen, PH, describes in his later writings how the increased efficiency of the light bulb made it necessary to solve scientifically the problem of glare from the light source using geometrical and arithmetical calculations. It was very important to him to be able to make corrections to the spectrum of light radiated, in particular the cold blue. One possibility was to use different coloured planes of reflection in the light shades.

A large commission to design the light fittings for the renovation of the Thorwaldsen Museum under Kaare Klint, gave PH the opportunity to develop his first new and modern series of lamps, consisting of one ceiling and two table lamps. It was at this time that the professional collaboration between PH and Knud Sorensen began. The geometrical investigation of light rays led to elliptical lampshades in which the light was to be precisely in one focus of the ellipse. These experiments had been preceded by earlier ones with paraboloid shapes – four a Street lamp, of which a few examples were put up in Copenhagen.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The Paris Exhibition of 1925 was approaching. A competition to select participants was helt in 1924, for which PH submitted his first models. His work with the supplier Louis Poulsen began at this time. PH and Knud Sorensen together with Poulsen won, giving them the opportunity to design the lighting for Kay Fisker’s Danish Pavilion. They also supplied all the lights for the Danish section in the Grand Palais and were given a special area to exhibit their new series of lamps. They were manufactured by Lauritz Henriksen’s Metalvarenfabrik supervised by Louis Poulsen.

Six models with ten variations called “PHsystems” were presented. PH was awarded the gold medal as the designer and Poulsen a silver medal as supplier. Both the pendant lamp and the globe light in the pavilion won great acclaim but thanks to a small mishap the way was opened to an absolutely glare-free lamp which radiated and scattered light indirectly.

When the Danish section was being set up it became evident that more lights than planned were needed for the main room. Four additional lamps had to be designed in such a way that they could be produced at very short notice in Paris. They had already noticed that the polished surfaces of the lampshades of German silver dazzled mercilessly but it was impossible to make any improvements. The additional light offered the opportunity to experiment with lightweight material which would give a diffuse reflection, possibly a textile reinforced by steel wire.

After the experience in Paris the opportunity arose for PH to enter a competition to find a supplier within the Danish trade fair for the lighting of the Kaemphallen which were being built at the time (later known as the Forum). The competition was tough and it was essential to tender a lower bid than the German manufacturer Zeiss & Goertz. A special feature was the type of object to be lit – motor cars in a large hall. PH developed for this the lamp with three shades which was the prototype for the PH lamp system. It was put forward for production.

All the problems which had been recognized in Paris could be solved in this utility light. With a sliding mechanism it was possible to adjust the height of the fil ament to achieve the right geometrical relationship to the shades and avoid or correct any glare, the choices of different surfaces for the lampshades – shiny or matt metallic, glassy, transparent, etched glass or milk glass – made a range of subtle nuances in the light possible and the scattering angle of the light rays in the room made it possible to light very different objects ranging from horizontal to vertical surfaces with absolutely glare-free, diffuse light.

The success of the PH system was overwhelming and the physiological benefit of these lamps, particularly in work spaces, was recognized. Poulsen and PH remained active, making the system so precise that any lighting task could be fulfilled. Pendant lamps, wall lamps, floor lamps, lights for workplaces, for doctors and even for greenhouses could be included in the same series. They worked particularly intensively on colours of light. Poulsen supplied shades which were not only of different sizes, materials and surfaces but could also reflect the light using different nuances of colour, so that, according to the particular requirements of an application, shades of colour could be corrected using the inner reflecting surface of the lamp.

The versatility of the PH system, but also its form, which was so self-evident it might have been developed from a diagram explaining a phenomenon of physics, contributed to its widespread use by modern architects. The culmination was their use to light all the main rooms in the Tugendhat Villa in Brno designed by Mies van der Rohe.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

But the patenting of the lamps took a long time, a total of four years from 1924 to 1928. Only with the help of studies by various professors they managed to find the right wording for the patent. The principles of reflection, scattering and glare-free light in combination were recognized as being an extraordinary achievement. But PH’s inventor mentality did not stop with the three-shaded lamp. Wartime with the typical phenomenon of blackout brought about the development of tested models for the Tivoli Amusement Park.

The rapid increase in traffic also stimulated further research into street lighting and once more PH broke new ground with a proposal for a symmetrical lighting in the direction of the traffic flow, a system which incidentally is still in use today. The pendant lamp was modernized in 1958. When the PH5 pendant lamp was presented it was hailed as a “classical innovation”, in PH’s own words: “After 33 years of faith in Christianity I have converted to Islam when it comes to the manufacture of electric lights”. PH developed the new lamp for every type of light bulb in every possible size and shape. The PH5 with four shades and two coloured reflecting areas became the epitome of Nordic lifestyle and became the showpiece of Danish design. PH did not live to see the development of the energy saving light: he died in 1967.

After 33 years of faith in Christianity I have converted to Islam when it comes to the manufacture of electric lights.

Poul Henningsen

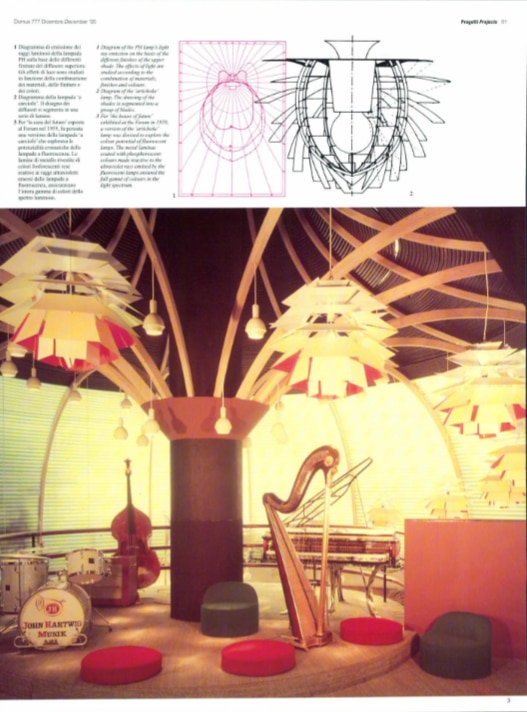

In 1995 Louis Poulsen presented the PH pendant with an energy-saving facility. The globe lights were developed in parallel to the PH5. Coloured reflection fans were added to the circular shades. According to how the height of the light bulb in the lamp was adjusted the light was corrected with blue or red: the contrasting light. The round shades were broken down into individual reflectors which is how the eccentric “artichoke” came into being which can be fitted with a 500 W or 1000 W bulb. Louis Poulsen always remained loyal to the light bulb and after the war the modern architects Marianne and Hans Wegner and Arne Jacobsen added high-calibre designs to enhance the production range of this important promoter of Danish design culture.

This article is based on the book by Tina Jorstian and Poul Erik Munk Nielsen, Light Years Ahead. The Story of the PH Lamp. Copenhagen 1994. Special thanks to Ida Praestegaardfor her support.