“Architecture is used only as a pretense for speaking about other topics: physics, society, communication, graph theory, environmental economy, even about politics. In all those fields I was helped by my naivety and my lack of erudition. A friend of mine, the writer Robert Jungk, used to call me ‘the child who discovered that the emperor is naked’”.

In the nearly 100 years of his existence (born in 1923, he died in Paris in 2020), the Hungarian designer and theorist, French by naturalization, constantly dedicated to questioning common assumptions about architecture and cities, becoming an inspiration for entire generations of practitioners and thinkers, from when he destabilized the tenth CIAM in Dubrovnik in 1956 with his “mobile architecture”, to his famous Ville Spatiale made of evolving matrices in the air recalling Constant Nieuwenhuys's New Babylon, to the 2000s of his blogging activity and research on survival architecture.

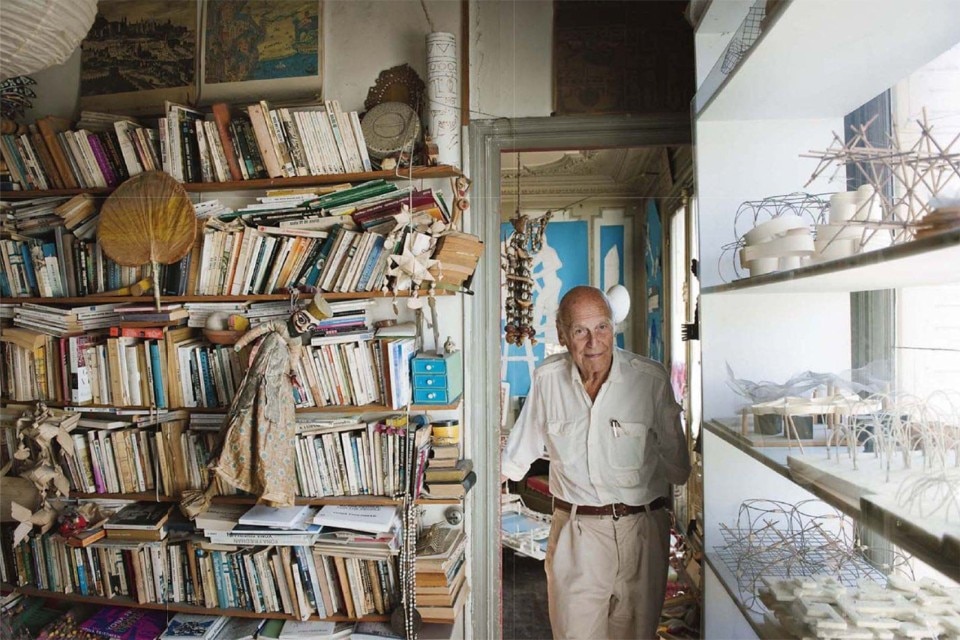

In the last decades, Domus had a very intense exchange with Friedman, also made of visits to his home-studio in Paris. The one that Domus published in November 2005 on issue 885 had also been an opportunity to unpack his library, diving deep into a landscape of lifelong references.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Unpacking my library

Yona Friedman’s house in Paris is a masterpiece in itself, the creation of a mental world in the form of furniture and accumulated objects, of home-designed tapestries and marvellous statements of Talmudic wisdom: the first supreme truth is that the world is made up of numberless erratic events, each of which in its individuality is more important than their vision as a whole. Yona Friedman’s pencil, which governs first his brain and then the monumental variety of his works, both realised and unrealised, as well as his extraordinary corpus of books and thinking by images and designs, is present everywhere: in corners, on tabletops loaded with light bulbs once used for an exhibition and now piled into a pyramid that illuminates nothing; on shelves crammed with books and on crumpled visiting cards. In this space, everything seems to follow an apparently lawless but strangely consistent pattern. Each room emerges in a dominant colour. The one in which our conversation takes place about books in Yona Friedman’s life is in a brighter shade of blue-grey. Against this background are human figures cut out by the artist in person, following one another from panel to panel like figures in a grand dance to the music of earthly revolution.

Friedman politely mentions the work of some of the Italians he knows and admires. One of these is the editor of his works in Italian, the scholar and architect Manuel Orazi, who, under the titles published by Quodlibet in recent years, has added new sap to the appeal exerted by the work of this unique personality. Now aged 88, Friedman started life as a Hungarian Jew, continued for a short spell in Israel, and finally settled in France, though in truth he has always been in a continuous intellectual voyage throughout the universe of design. In Paris, Yona Friedman’s library contains thousands of books, for the most part stacked along corridors. But the author of Attainable Utopias, with his quiet English modulated by the typically hard consonants of the East and of those who have spoken Hebrew, announces at once that he won’t be picking out any actual book: the list is all in his mind. After all, every system or world generated by man is born and dies first of all in the minds of individuals, groups and communities.

Gianluigi Ricuperati

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The Ten Commandments, still more than the Bible itself, are for me a true miracle of expressive density. For me expressive density is the most important part of any discussion about books. Worlds are made up of expression, and worlds are more important than books, even though I have always been an avid reader and have accumulated a very large number of volumes. That is why I would like to start with The Ten Commandments, which are not a book but an infinitesimal portion of a greater book, though I believe they are crucial. Mind you, this is not a religious question, but a question of density.The Ten Commandments have formed the basis of a world, an entire civilisation, for centuries, millennia; and in part they still do, through a prodigious economy of language. The very few words have a gravity, in the physical sense of the term, that surrounds every sign. It is a masterpiece that establishes the beginning of a world through a concise system of laws.

Since all my life I have been interested in and attracted by the idea of creating worlds, or understanding how they are generated, or how worlds can be generated, I believe one must inevitably start from these ten laconic yet collectively very strong indications. In drawing, it is the same thing: it is important to adopt the greatest possible expressive density in order to communicate, which is what I have always tried to do, with my students too, in the exercise of teaching. One real book, truly a novel about the creation of worlds, is that Western literary classic The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann. Here, in a sense, architecture is brought into play. What interests me about the book is not the characters, not the story, but the physical setting, this superb place, this mountain sanatorium where civilisation, with its inheritances and differences, is isolated yet erased, only to start again and, in fact, to re-establish a world from scratch. It is an island apart, in the existing world, totally aloof from what is already part of its normal, accepted context. My curiosity is not aroused in particular by the characters, such as Hans Castorp, whose ideas and intellectual speculations have been the subject of entire essays, but rather by the original quality of the invention of a physical and moral, unexpected and surprising environment.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Something of the sort occurs in science fiction, so in my hypothetical list I would like to include a number of titles belonging to this genre. I shall choose one, perhaps the most classic and renowned of them all: Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury. In this case it is doubly interesting, and for this occasion too, seeing that it is basically the story of a group of men who completely rebuild a world after the total destruction of books and their forced absence from the world presented by the author.

Furthermore, I have always thought of Ray Bradbury’s book as a fictional version of the great ideas set out in a fundamental essay by Johan Huizinga, The Autumn of the Middle Ages, which in part heralds something of the atmosphere surrounding the novel. These are books that I read in my youth, in some cases as an adolescent, and almost all of them in Hungary. But I must stress that for me language and contents are far more important than the books themselves. What matters are the texts, the use of language and forms. The important thing is that they are vehicles of information. Books are of course very important for a person of my generation. But my granddaughter, for example, finds that same vehicle of information simply by touching the screen of her iPad.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Another subject that has pervaded my work is anthropology. For this reason I would like to mention the formidable work of Leo Frobenius and his collection of African folk tales. For me these have been a constant influence and attraction, and in the 1960s they also inspired a series of animations derived from the traditional tales selected by Frobenius. So when the Venice Biennale asked me to propose a work, I decided to base it on this ancestral folklore and to put it in a visual form, in the most dense and essential way. It is never the books in themselves that impress me, nor even their authors, although in my life I have travelled a great deal and have met prominent essayists, writers, philosophers, architects and intellectuals. What impresses me are always minor extracts, well-defined parts. At times I am not even as interested in their content as I am in their underlying structures, for these contain the seed of certain issues that are central to my mind, such as that of density.

I have always worked hard on the transmission of visual information, producing comic strips, graphics and illustrations. In all these vehicles of communication and expression, the basic aspect has always been the capacity to convey complex data through comprehensible, rich but straightforward signs. For me, though, books are above all an archive of information. One day Arthur C. Clarke, the author of the story from which 2001: A Space Odyssey was taken, showed me a cigarette packet. Opening it, he told me that the entire British Library could be reduced and stored in the space occupied by six cigarettes. I found it hard to believe him, but I did, and it seems he was correct. Books are not essential as objects, but as the accumulation of information. Nevertheless, in its turn that information must be essential to the mind that perceives and processes it. In a book it is not the author that matters, not the title, nor even the entirety of its text. All that matters is what your memory wishes to retain!

Yona Friedman