“I decided to create my brand after watching Le Mépris from Jean-Luc Godard, being inspired by the beauty and modernity of his vision”. So said Simon Porte Jacquemus on the eve of the ‘La Casa’ fashion show, crowning 15 years of his brand on one of the world’s most famous rooftops, Villa Malaparte in Capri. It is one more episode in the trend of choosing famous architecture to present fashion collections, still it carries a deep cultural stratification. Ever since its conception, this house has been a powerful catalyst of fascinations and different meanings, since it was generated from an extremely intimate exchange between the spaces, the place, and the personality of a client, Italian intellectual Curzio Malaparte in dialogue with rationalist architect Adalberto Libera: this is the famous “house like me”, the “house filled with unrequited stories” recounted by John Hejduk to Domus in 2012. And this place, more a psychological than physical place, is where Godard's exploration was born.

“Identifying the true and the beautiful with the pulse of reality, starting from the confrontation between individual neurosis and an oppressive social reality to develop a cinematic expression that is a weapon for psychological and political liberation”. This is how, in the 70s, critic Giovanni Grazzini would describe the cinema by the French New Wave maestro. Disruptive in its innovativeness in comparison to the previous “school”, by denying any organic narrative structure and breaching into the fourth wall (the side of the audience, of the camera, towards which the actors constantly turned), Godard’s work owed much to the generative power of its spaces: enough said just by recalling the rooms of the Louvre crossed on the run by the protagonists of Bande à part, or Brigitte Bardot’s presence superimposed on the very tiles of Villa Malaparte. It was precisely from this visual icon created through the photography of Le mépris that Piero Golia moved to pen his final cinema column for Domus, on issue 1030 of December 2018.

Every place of dreams is steeped in stories and legends

Another year, too, draws to an end. The days flash past with their problems, ideas and required solutions without time being a real concept in everyday life – so the end always arrives before you expect it.

Time never seems to disappear in this California of the seemingly eternal summer yet the months pass before you know it and you abruptly realise that another year has ended and this column has reached its grand finale. I wanted to talk about a TV series I have just started watching on Hulu. It is called The First and features Sean Penn leading an interplanetary expedition to Mars. Closing the circle with The First is like an exercise in style.

TV series appear to be the new cinema and, having seen the beginning, this one looks great. The first man on Mars may seem fantastic but I think my grand finale needs something more monumental, cinematographically speaking, a last contribution that goes to the heart of a magazine centred primarily on architecture and a column which speaks about films, although I have sometimes pretended to forget that.

My swansong – or rather the choked song of the goose, considering the monotonous tone of my voice – demands a fitting choice, a spectacular grand finale.

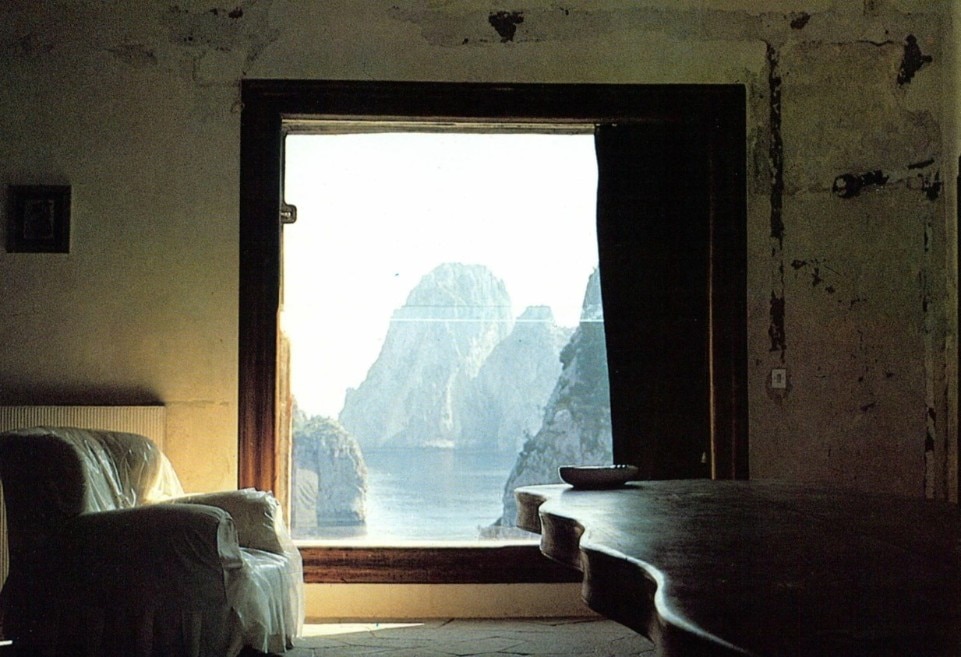

Being so obsessive, such a choice might have taken me years but this time, almost miraculously, I found it extremely easy to choose: architectural milestone meets cinematic milestone, the loveliest building of all, Casa Malaparte in Capri, filmed by the master film-maker Jean-Luc Godard. It is a house I have always only seen from the sea because it is impossible to get inside, although I have always dreamt of exploring it.

Before Google picture searches could satisfy the curiosity of anyone with Internet access, there were libraries for academics and, for the lazier like me, there were films. It was during my search for pictures and accounts, hopeful of seeing the interiors of this architectural masterpiece, that I first came across the film Contempt (Le Mépris).

I paid scarce attention to the film itself at the time, watching it several times fast-forwarding the scenes and pausing only at the parts showing Casa Malaparte, with a very young and beautiful Brigitte Bardot wandering through the villa’s rooms or sunbathing on a terrace set sheer above the sea.

Fantastic shots of boundless horizons, impossible staircases and geometric edges showcase the building in all its splendour, its modern rationality complementing the natural environment. Constructed on the Faraglioni of Capri, it is inaccessible and has to be conquered up a long flight of steps that turns into a unique terrace overlooking the sea.

Conceived by Adalberto Libera for Curzio Malaparte (the pseudonym of Kurt Erich Suckert, author of The Skin), the villa is the product of a clash between the two almost opposing personalities. Malaparte rejected Libera’s design and built the house on his own with the aid of a local stonemason called Adolfo Amitrano – think Rationalist masterpiece revisited from a Surrealist angle.

Every place of dreams is steeped in stories and legends, and this villa no less so. To the arguments between client and architect add transport on muleback during its construction, famous guests, evenings with Gurdjieff, an angry Malaparte’s gifting of the villa to Communist China and the endless legal battles before his heirs regained possession of this priceless architectural masterpiece. Only in a film… Indeed.

So, at last, I watch the film again, from the beginning this time without any fast-forwarding. I discover onethat speaks of personalities and constructs impossible narratives, somewhat like the impossible geometries of the villa. It has all the magic of a Godard film and a beauty that is captivating.

There is something totally magical in this film, where the interwoven narrative of stories and non-linear situations comes to life in the personal universe of its characters. They are what is striking, the characters, with their singularity and personalities seeping through in the images. Godard manipulates them, constructing what turn into real stories. It is exemplary of the film based on well-constructed characters that no longer exists.

I will not tell you the story of the film because it is worth watching if you have not already seen it, and give it the attention a masterpiece deserves. As for me, I am handing back and salute you with this goose song, with this testimony to the eternity of films that pay homage to the beauty of architecture.

A year I had imagined would be long has passed, although the desire to keep telling you stories remains.

Piero Golia, born in Naples in 1974, is an Italian conceptual artist. He is also the director of a metaphilm, Killer Shrimps, from 2004.

Opening image: Villa Malaparte in Capri. Photo Sean Munson from Flickr