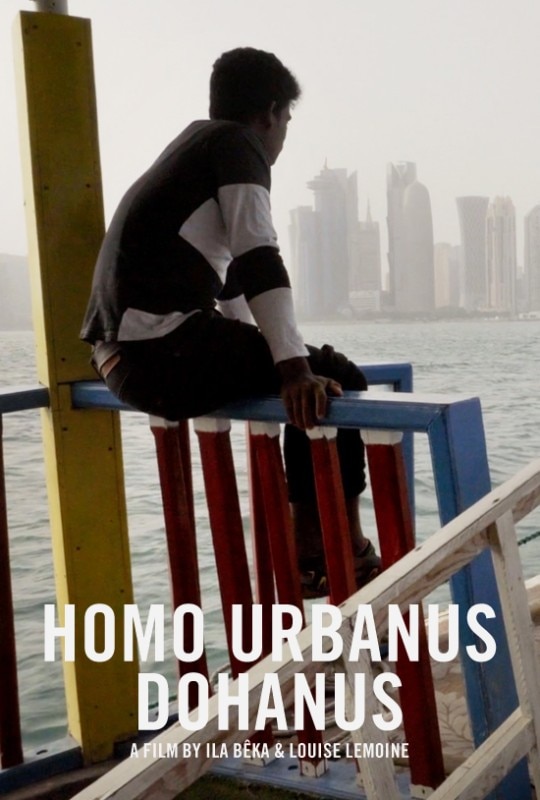

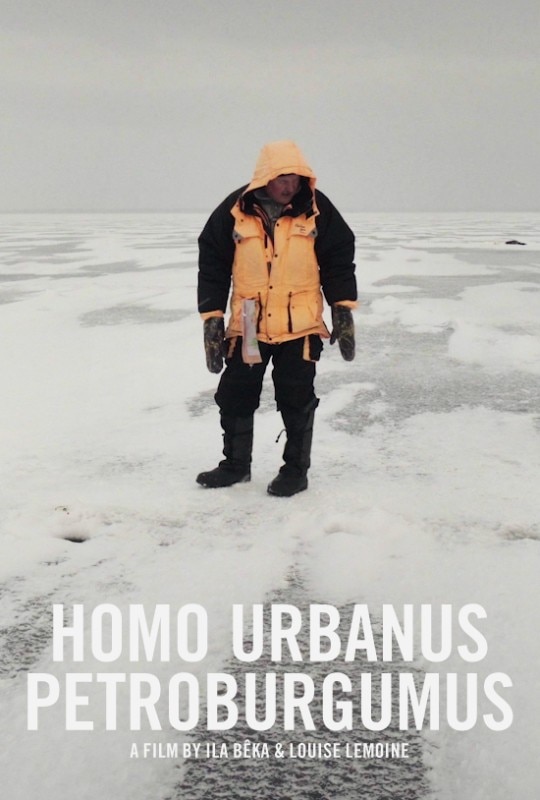

The two most famous architectural filmmakers, Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine, are offering to Domus readers the complete version of their latest film Homus Urbanus Venetianus, until Sunday 1 November 2020. To watch the movie just click on play. The movie is part of a collection of ten films on the relationship between man and city: the theme will also be at the center of the next Domusforum, the event organized by Domus that will take place on streaming on Wednesday, November 4, where special guests will oversee the theme "Future of cities". Emanuele Quinz interviewed the creative duo for us.

The episode about Venice (Homo Urbanus Venetianus) marked the tenth stage of your film cycle Homo Urbanus. How did the project for this “Odyssey” start?

Louise Lemoine: We’ve been collaborating for over 15 years now. Ila studied architecture, and I studied art history and cinema. We both felt that the relationship between architecture and cinema could be our common ground, which was still partly unexplored. Our first works dealt with the scale of architecture, of the building, but little by little, through a long series of films, we got to the square, the shared public space, and the city. The scale of architecture forces us to deal also with its designer, while the city is an open, collective and anonymous work, made up of historical sedimentations of which the designer can no longer be traced, and thus allows us to deal with new and more complex issues, and to open up more anthropological perspectives.

Ila Bêka: The film cycle wants to tell the city in a way that is as close as possible to the physical, sensory and emotional experience of the citizen. To understand how the city works, instead of proposing a rational analysis of data and information, we want to relive real situations. We are very interested in the methodologies of anthropology and participatory observation. There is a phrase by director Jean Rouch that we find really inspiring: “first, you film, and then you can conceptualize”. First you have to live the moment, and then you can try to understand it.

In the movie about Venice, the sequences oscillate between landscape and event, between the evocation of Canaletto-style eighteenth-century views and the sometimes comical, sometimes dramatic documentary chronicle of an exceptional situation – the Venice High Tide of 2019.

L.L.: The focus is on the relationship between the dominant atmospheric element, water, and the human being. Showing humans struggling with the urban context is a recurring theme in many movies – people trying to survive, to adapt to an extreme environment. In the case of Venice, we wanted to show the suffering, the fatigue of the inhabitants trying to find normality in a historical event that paralyzes the city, blocking the most essential processes, from electricity to food supply. We wanted to pour this effort on the viewer, to arouse a form of empathy.

I.B.: The cinema we make is a cinema made of suggestions. We avoid the use of voice-offs that explain how to interpret images, or music that basically does the same thing. The power of cinema lies in being able to suggest feelings and emotions without having to explain them. The moment must be lived as it is presented.

The title of the film cycle, Homo Urbanus, follows the name of the scientific classification of species, like Linnaeus’. And above all it seems to show that, despite what most people thing, it is the cities that define the inhabitants.

L.L.: Today, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities. The expression Homo Urbanus stands for the last stage of evolution of the human species after the Homo Sapiens. The history of the city is a dynamic of continuous adaptation, of urban and human structure, an uninterrupted and tormented process of mutual transformation.

You pay very close attention to the public space – the space of (public) power or freedom?

I.B.: The modern city or, as Rem Koolhaas used to call it, the “generic city” is eliminating all the spaces that we cannot control. In the film, we focus on neighborhoods where space still belongs to the public – not to the institutions, but to the inhabitants. Areas of resistance, of freedom, where micro-economies are developing, and which must be protected because they are on the verge of extinction. The architecture or the master planning of cities are powerful devices for controlling public life and tend to produce order, normality and homologation. Our films show how the relationship between order and vitality is inversely proportional – the more order and control there is, the more the city tends to lose its vitality.

L.L.: We are very interested in cultural variability in the understanding of public space – what is done in the street and what is not done. For example, in Naples the inhabitants reclaim part of the street to build an entrance or a terrace for their home. In Kyoto, the inhabitants take care of public space to make it more pleasant for everyone, giving it a sacred value. In Shanghai, there is a porosity between inside and outside, the inhabitants use the street as an extension of the dwelling: they eat there, brush their teeth, hang their clothes up to dry. Comparing these behaviors from one culture to another allows us to relativize our positions.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw images of cities completely empty, ghostly, like in De Chirico’s paintings. What effect did it have on you?

L.L.: The need for social life has not died out, but has moved into the virtual dimension. Today, the public square, the real city, is represented by Zoom and other virtual platforms. The pandemic has accelerated some changes that were already happening, making a paradox evident. On the one hand, we are experiencing an extreme hypermondialization, we are connected with the whole world at any time. On the other hand, by reducing our movements, we have become hyperlocal. Our generation of nomads, who for work or culture reasons used to take the plane once a week, thanks to home working, now stay at home and rediscover the advantages of the local dimension. The urbanization process, which seemed irreversible, is being reversed – the inhabitants start to move out of the big cities, to live in small towns or in the countryside, to seek a new quality of life.

What will the cities of the future look like then?

I.B.: The health crisis we are currently going through is dramatically revealing the limits of the modern city’s development project. Even the much-praised model of smart cities clashes with reality, thus producing new forms of subjection. Contrary to certain gurus who offer us predictions based on seemingly unassailable data and statistics, we think that the best way to understand the future of cities is to observe the present. Our future finds its roots in what happens in the streets today.

Opening: trailer of Homus Urbanus Venetianus by Bêka & Lemoine, 2019. The full movie was available for Domus readers throught the last weekend of October 2020, on this article.