“Fashion stores are also phenomena linked with the design and costume field,” indeed they are “absolute protagonists of the phenomenon”, where “clothes are an aspect of it but not the whole of it”, wrote Domus 659 in March 1985, at the height of the roaring Milano da Bere and of the renaissance of Italian fashion in the world. This before venturing into an examination of several boutiques for brands such as Mugler, Magli and Commes des Garçons.

The symbiotic relationship between architecture, design and haute couture, however, was not an ephemeral affair like the Milanese fashion season of the Eighties, but an intense and close-knit journey. Over the years, starting with the post-World War II economic miracle, the boutique has gone through a series of transformations dictated by the evolution of social dynamics and made possible by its dialogue with design and architecture.

What triggered this process as far back as the 1960s, according to Domus 460, was the reversal of perspective and roles: the designer became an architect, and the architect became a stylist of environments, “making interior design a mimesis of the style of the season”. The initiator of this revolution was, according to the magazine directed by Gio Ponti, Paco Rabanne, defined as the “architect of women as weapons”, for his desire to emancipate the female body through “dress design”.

If at the beginning of the 1960s the boutique was an intimate and essential environment, devoted to the pragmatic needs of a fashion industry to be experienced strictly behind-closed-doors, from the second half of the decade it became a pop and community environment, aspiring for the involvement of a younger and more heterogeneous public.

This is highlighted by a 1960 project by architect Paolo Chessa for a showroom for a Milanese tailor’s (Domus 372), where haute couture, still far from pret-a-porter, mirrors its exclusivity through mid-century interiors punctuated by the research for Mondrian-like and constructivist palettes, with primary colour upholstery for the sofas and walls covered in fir panels.

Disco or boutique?

From the mid-1960s, the rise of the newly-born figure of the teenager as the fulcrum of consumerist society jointly with the countercultural turmoil, contributed to the vanishing of the line of demarcation between the environments conceived for clubbing and for fashion. Take Superstudio’s design for the Florentine discotheque Mach 2 (Domus 473) which hosted a boutique inside it, an idea also envisaged by the Atelier d’Urbanisme et d'Architecture for the Theatre de la Ville in Paris (Domus 475).

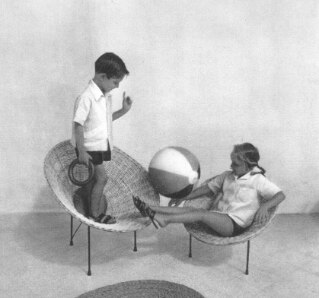

Conversely, the Metalsadi metal panels used for the interiors of the radical design discotheque Altro Mondo Studios in Rimini designed by Pietro Derossi and Giorgio Ceretti recall those of a shoe boutique in Milan by architect Sergio Asti (Domus 467).

Of these boutiques, the unique, modular ambience is highlighted – as in the Follies Shop in Saluzzo, Cuneo, by Lorenzo Prando and Riccardo Rosso (Domus 539) –, reminiscent of the radical discotheques or “funfairs” by Pietro Derossi and Giorgio Ceretti that Domus 458 reported on in January 1968.

“Neither the Piper-pluriclub in Turin, nor l’Altro Mondo in Rimini are real environments. That is to say that, in addition to being sound boxes, they are not rigid structures that impose a style, a characteristic atmosphere, and a fixed clientele. Rather they ar enormous containers that contain the appropriate pieces for constructing an environment every now and then. They are a bit like those sets of building blocks with which we once played at being architects.”

Artists and designers, “hungry for these aluminum and nickel-paneled spaces” are indeed the bridge between the boutique and the discotheque. The “light machine” at Turin’s Piper is, in fact, the work of Bruno Munari, while the venue was also used as a performance space by the likes of Gerard Malanga and Le Stelle di Mario Schifano with “Schifano exciting both Le Stelle and the audience with flashovers of slides, films and stroboscopic lights”.

Dressing the counterculture

In Italy, too, Rome’s Piper club launched the boutique Piper Market, while band Equipe 84 opened (even anticipating the Fab4) a clothing bazaar inside an old grocery in Milan's Via Solferino, preserving the period façade. Needless to say, the Emilian band's adventure was as short-lived as that of their Liverpoodlian colleagues.

In Genoa, the children’s clothing shop Le Zanzare (Domus 441) designed by Gianfranco Frattini (also the creator of a textile shop in Via Bagutta in Milan, Domus 465), seemed to embody the spirit of 1968, echoing the name of the student newspaper of the milanese high school Liceo Parini that in February 1966 had led to a national uproar publishing a progressivist story about the role of the emancipated woman in the society of mass consumption.

To represent the role of the boutique in the broader context of the Italian counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s is the significant number of projects to which radical architecture groups devoted themselves in parallel with their work on discotheques. In addition to the aforementioned shop by Ugo La Pietra, in 1972 in Milan Nanda Vigo designed the King Kong jewellery shop (Domus 506), while a couple of years later in Turin Studio 65 made the Skin Up leather goods shop (Domus 537). Similarly, in Tuscany, UFO enhanced the conceptual bond of Versilia with the European underground by conceiving the Londonesque Wizard of Oz boutique in Viareggio (1969) and Saga De Xam in Florence (1969), inspired by the French science fiction comic of the same name.

But also the Milk Boy boutique (a brand still existing these days) designed in 1974 in Tokyo by Shiro Kuramata (Domus 540), which both in its total white interiors and in the name seems to nod to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, which back then had just come out in cinemas.

Fashion is a spatial illusion

A common thread running through many of these boutiques is the search for the illusory nature of space, as if the designers’ desire was to replicate the illusion and ephemerality of fashion. If at the beginning of the 1960s this was achieved by modulating the available spaces as in Paolo Chessa’s tailor’s shop in Milan, later on it was metal and reflecting surfaces borrowed from the architecture of entertainment that accomplished this mission, as in the Milanese Valentino boutique designed by Aldo Jacober with the collaboration of Cristina Annoni and Fiorella Butti (Domus 489).

Such a trait is also at the core of the Box boutique, designed by Ubald Klug: a clothing shop in Bern located underground, underlining the renewed countercultural dimension of fashion.

Similarly, the boutique Altre Cose, again a project by Jacober, here together with Ugo La Pietra and Paolo Rizzatto, features large transparent cylindrical tubes as display stands hanging from the ceiling and is connected by a lift, also transparent, to the Bang Bang discotheque below. The result is an “environment-instrument in which optical and sound effects and the electronic movements of the parts transform functioning into play”.

However, it is Richard Carr who ideally wraps the decade up in Domus 480 by critically reflecting upon the long-term practicality of such radical design solutions: “At first no one questioned having to buy clothes in dark interiors, with black ceilings and purple walls, or minded if the shop was so secretive, that it was impossible to see inside. But now that with-it fashion is no longer confined to the Kings Road, but may be obtained in any good department store, that is no longer true, and the scene so to speak is losing its appeal.”

Opening image: Shoe shop, Sergio Asti, Milan, 1968. Photo: Domus 467, October 1968.

Sahil: G.T.DESIGN's Eco-conscious Design

At Milan Design Week 2025, G.T.DESIGN will showcase Sahil, a jute rug collection by Deanna Comellini. This project masterfully blends sustainability, artisanal craftsmanship, and essential design, drawing inspiration from nomadic cultures and celebrating the inherent beauty of natural materials.