Brian Peter George Eno, also known as Brian Eno, born in 1948, is a British visual artist, composer, producer, and an undisputed genius of contemporary music. Eno revolutionized the 20th-century soundscape with his seminal work, Ambient 1: Music for Airports, released in 1978 by Polydor Records. This album not only defined the “ambient” music genre − so named by Eno himself − but also redefined musical composition by treating sound as a matter of design.

Known for his pioneering use of synthesizers with Roxy Music and for his collaborations with renowned artists such as David Bowie, Talking Heads, and U2, Eno ventured into new sonic and conceptual frontiers in the 1970s. “Music for Airports” marked a significant shift from traditional listening to a new conception of the “soundtrack,” designed not to accompany images but to transform environments, complement spaces flooding them with sound and redesigning their emotional.

Portability and Abstraction

The 1970s: a decade that brought us the Boeing 747, making distant destinations more reachable, the Polaroid, transforming photography into a portable studio experience, Post-its, which were the result of a growing need for systematic mnemonic organization, and the Sony Walkman, which forever changed the way we experience music, allowing us to color our journeys with personal soundtracks. This is also the era that identified abstraction and chromatic coding as the keys to interpreting the subway maps of big cities: in 1972, Massimo Vignelli redesigned New York's intricate subway system, stripping away the “overground” to focus on a chromatic network of lines punctuated by Helvetica nomenclature.

1977, the year of punk, of the Clash, of Never Mind the Bollocks by the Sex Pistols, of Rocket to Russia by the Ramones, of Trans Europa Express by Kraftwerk; but it’s also the year of Brian Eno's great collaborations with David Bowie (Low and Heroes). 1977 is the year in which waiting for a plane at the airport in Cologne turned into the engine of a momentous change. During that dead time, Eno wondered what kind of music is best suited to be played in a facility like that, particularly having in mind people who are about to fly and therefore are in a state of apprehensive mood. So, he began to conceive and then assemble the relaxing and reflective tracks of MFA, with the specific purpose of using them in airports. The result are tracks capable of inducing serenity with their placid dynamics, a small catalog of ambient music suitable for a wide variety of moods and atmospheres. Rather than "covering" the noises of a given environment, Eno imagined sounds that can increase the emotional resonance of the space, favoring sounds that encourage calm and reflection.

This album not only defined the ‘ambient’ music genre, but also redefined musical composition by treating sound as a matter of design.

The record was actually released at several airports, including New York's LaGuardia, Minneapolis-Saint Paul, São Paulo-Guarulhos, Stansted in 1998, and Düsseldorf in 2011. Unlike ordinary records meant for domestic listening, Music for Airports operates on a broader scale, in which the lives of numerous people dynamically intertwine.

Stylization of an Environment

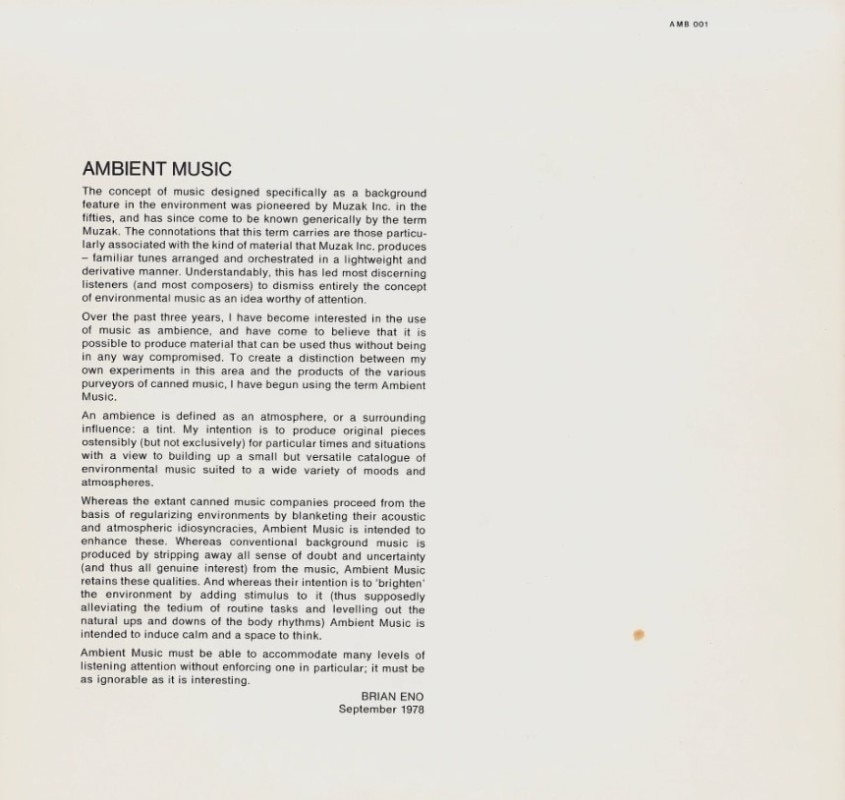

Is it a segment of a geographical map? An aerial view of lakes, rivers, deltas, depressions, highlands, and forests? Or perhaps an image created with Ben Day dots − a technique beloved by Roy Lichtenstein − that produces variously colored areas through printing and photogravure. Green spaces, blue lines, white splotches define slanted landscapes. This is what we see as on the cover of Ambient 1: Music for Airports. An image that immediately transports us into a precisely undefinable environment that is simultaneously stylized and abstract, perfectly setting the “flavor” of what we are going to listen. After all, when Brian Eno created MFA, he was searching for functional music that could "color the air" to fit certain moods − the sonic equivalent of a sophisticated room scent. This quest of his was a stark contrast with the established form of ambient music at the time, which was predominantly “easy listening” or Muzak: orchestral arrangements of pop hits rendered in a light, derivative manner.

The cartographic abstractionism of the “Music for Airports” cover evolves through the subsequent albums in Eno's ambient series − Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror by Harold Budd, Ambient 3: Day of Radiance by Laraaji, and Ambient 4: On Land. Red dithers overlay plains, highlands, and rivers, gradually zooming in to make the pattern more apparent and leaving room for circumscribed white areas − clouds or lakes? − and intricate dot patterns.

Sound: A Matter of Design

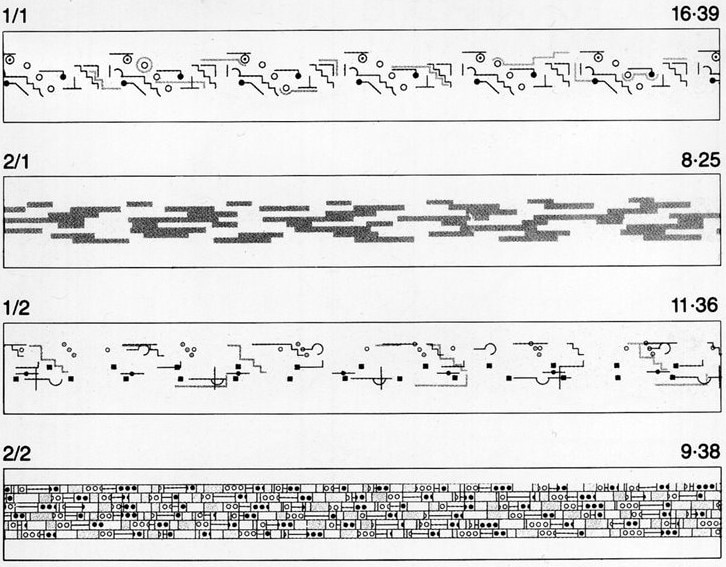

MFA was released in 1978 in cassette and LP formats. It was made of four tracks: “1/1,” “2/1,” “1/2,” and “2/2,” corresponding to the first and second tracks of sides A and B. There are no lyrics or conventional songs; instead, each piece is organized into groups of sounds that repeat at irregular intervals, utilizing tape loops and synthesizer overdubs. The scores, included in the liner notes, are images drawn by Brian Eno himself. Unable to read or write traditional sheet music, Eno employed graphic symbols to convey each phrase. On close inspection, one can see dots, straight and curved lines, circles, scales, and parallelepipeds, spaced differently on each line, reflecting the recording techniques used to create the album.

Analyzing the record as a whole, it becomes clear that the notes are suspended in a space akin to a painting, with shapes and colors juxtaposed without an audible logic connecting them. This design of sonochromatic relationships is untethered from narrative development. As music sheets on tape, the tracks on MFA are visual textures rather than instructions for performers. With this album Eno seemed to express the idea recorded sound can be manipulated to the point of becoming almost plastic, like clay in a sculptor's hands. In this perspective, “ambient” is a variable function music can have that delineates atmospheres and nuances, even moods, interacting with broader acoustic and social contexts. Eno did not conceive and designed ambient music to completely absorb the listener's attention; instead, it represents a bizarre perspective, a perceptual repositioning of the Self in space. This sonic tint can accommodate multiple levels of attention without imposing one in particular. Ignorable yet interesting, MFA enters the listener's life in an oblique, delicate, but inevitably transformative way.

Aesthetic and Prismatic Listening

Predicting the melodic development of the tracks on “Music for Airports” is impossible, there is no technical virtuosity, and the relaxing disorientation it induces in its listeners raises intriguing questions about its creation and approach. The tension these questions create transports us into the realm of conceptual art, in a similar way Marcel Duchamp's Fountain did in 1917.

An image created with Ben Day dots produces variously colored areas through printing and photogravure. Green spaces, blue lines, white splotches define slanted landscapes.

MFA functions as a theoretical treatise that configures the sound field not merely as a musical work but as a dynamic and unpredictable interaction with the design of any space − physical or mental − it encounters. In this expansive ecology of listening, the work, the artist, the listener, the technologies used, and the environments they inhabit resonate together.

With “Music for Airports,” Eno pursues sound modes that invite listeners to engage in a nontraditional manner, appreciating the non-musical characteristics of sound as an “aesthetic object,” prismatically amplifying awareness of different sensory perceptions.

The Legacy of “Music for Airports”

Ambient 1: Music for Airports is rightly considered the manifesto of the ambient genre. Brian Eno continued the series with “Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror by Harold Budd, Ambient 3: Day of Radiance by Laraaji, and Ambient 4: On Land. Selected Ambient Works 85-92 by Aphex Twin and William Basinski's Disintegration Loops – just to name a few − are crucial examples of how the genre created by Eno expanded since his initial series. But the influence of this album extends beyond ambient music. Artists from various genres − from electronic music composers to pop music producers − have cited Eno as a source of inspiration. Moreover, the concept of using music to enhance public spaces has been widely adopted in diverse contexts, from art galleries to hospitals.

Therefore, MFA is not just an album, but a revolutionary concept that changed the way we think about music and its role in our daily lives. With his vision, Eno has created a work that offers itself to the 21st-century public as an oasis of calm in an increasingly hectic world. For the experimental and ambient music neophyte who does not know where to start, there can be no better introduction.