Early 1970s. In Italy, the long wave of the ’68 protest is culminating in a situation of radical conflict that affects not only socio-economic structures but also visions and projects in the artistic and cultural spheres.

Among the most representative design products of that period is undoubtedly the Aeo lounge chair designed by Paolo Deganello for Cassina. While the Archizoom experience is in a declining phase, Deganello orients himself towards increasingly solitary design, leading him to conceive this lounge chair as a polemical reaction, perhaps even as an antithesis to Tobia Scarpa’s Soriana – also produced by Cassina and awarded the Compasso d’Oro in 1973.

Deganello sees Scarpa’s creation as a swollen and opulent armchair, dripping with rich and soft foam, emblematic and paradigmatic expression of that design of well-being, luxury, and comfort that Archizoom systematically contested at its roots with dedicated devotion.

Aeo is born precisely as a reversal of that paradigm: made with the common canvas of deck chairs, with steel springs, bent tubes, and Moplen plastic (the one Gino Bramieri advertised on Carosello). In fact, it aspires to be the equivalent, in the field of design, of what Arte Povera was in the artistic sphere. Deganello’s idea finds immediate resonance at the Cassina research center: there is a strong drive towards innovation, experimentation with new materials, and the creation of products that can appeal to a younger audience in companies.

Deganello, with Francesco Binfaré, the director of the research center, and his collaborators, as well as Cesare Cassina himself as interlocutors, proposes to radically redefine the concept of the chair, starting from the idea of a seat capable of adapting to the shape of the human body that chooses to sit on it. However, the innovation does not stop there: anticipating in some ways Ikea’s philosophy, initially Aeo is shipped disassembled, and the user is invited to assemble it themselves, customizing the object by choosing which components to purchase.

In fact, Aeo – with the aim of overcoming the ideology of the modern and the fetishism of identical pieces – is available in different versions. Users can choose to purchase it with or without armrests, it can be assembled in a straight line or in a semicircle, can even give rise to sofas for two hundred or three hundred seats, with or without storage, and the cushion and backrest covering, made with various differently decorated versions, are easily removable and washable.

Promotion and communication are also highly innovative and closely aligned with the spirit of the times. Deganello requests that the armchairs be transported around on a truck and then placed in public spaces, markets, or squares in Rome, to let people on the street try them out and then discuss the validity of the product together. In the intention of its creator, Aeo aims to be a popular piece and a ‘poor’ object. As Deganello himself says, ‘We chose and hoped to be chosen by those same individuals who seemed to us bearers of new and more human life projects, by those young people who occupied faculties with us, participated in street demonstrations, and dreamed of changing the world.’

For Deganello, Aeo is aimed at those who hate waste, dream of widespread and collective creativity, want to customize objects, and co-design the form and meaning of the product. But the first disappointment comes with the price, which is certainly not popular. The second disappointment comes with the company’s decision to produce, against the designer’s will, a version of Aeo in leather instead of the more humble and simple deck chair canvas.

Even today, 40 years later, Aeo continues to be sold as an innovative product, but already assembled and in a single version, at a price that clashes with its vocation as a ‘poor’ object. This leads Deganello to think – in his own words – that ‘in this society, the innovative product is inevitably and inexorably elitist.’

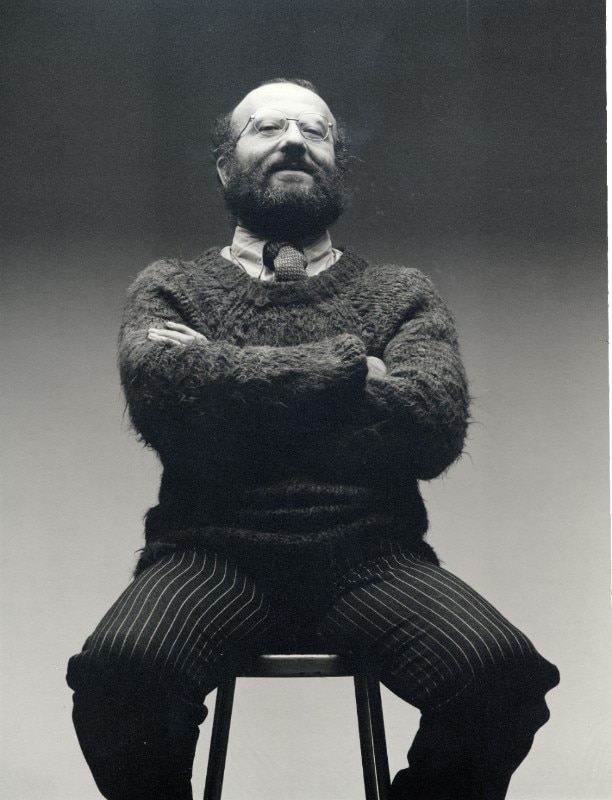

Opening image: Aeo armchair by Paolo Deganello – Cassina

Timeless icons: the Marenco sofa by arflex

Designed by Mario Marenco, this masterpiece of Italian design has set the standard for over fifty years.