In the early 1950s, in the area of Milan’s historic center to the immediate south of the city’s cathedral, surrounding the ancient street axes of corso di Porta Romana and corso Italia, Second World War’s ruins are rapidly leaving room to new constructions. Office and residential complexes by Asnago and Vender (1950-1952) and by Luigi Moretti (1951-1953) have already been completed, amongst the others, standing out as two excellent and personal Italian interpretations of architectural modernity.

A short distance from both buildings, 1951 marks the opening of the working site of the Torre Velasca, commissioned by the Società Generale Immobiliare to the Milanese firm BBPR, founded in 1932 by Gian Luigi Banfi (1910-1945), Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso (1909-2004), Enrico Peressutti (1908-1976) and Ernesto Nathan Rogers (1909-1969). Opened to the public in 1958, the tower is universally acknowledged as a pivotal episode in the history of 20th century architecture, one which in many regards concludes the age of the Modern Movement.

In fact, the Torre Velasca is not simply the most famous of BBPR’s realizations, but also the most faithful built transcription of Ernesto Nathan Rogers beliefs. At the time, Rogers engages in a process of re-interpretation of the discipline’s theoretical foundations, also through his activity with the magazine Casabella Continuità, which he directs from 1953 to 1965. New notions, such as “pre-existence”, “ambiente” and “continuity” become part of the architectural debate.

Overtly opposing the idealism of the Italian architectural culture from the previous decades, Rogers draws inspiration from philosopher Enzo Paci’s phenomenology, to re-situate architecture within its contexts and, in a broader sense, within a seamless historical continuum. While the Modern Movement had repeatedly claimed its intention to break away from the past, Rogers creates new bonds with it, to formulate the idea of modernity meant as an evolution, rather than a revolution.

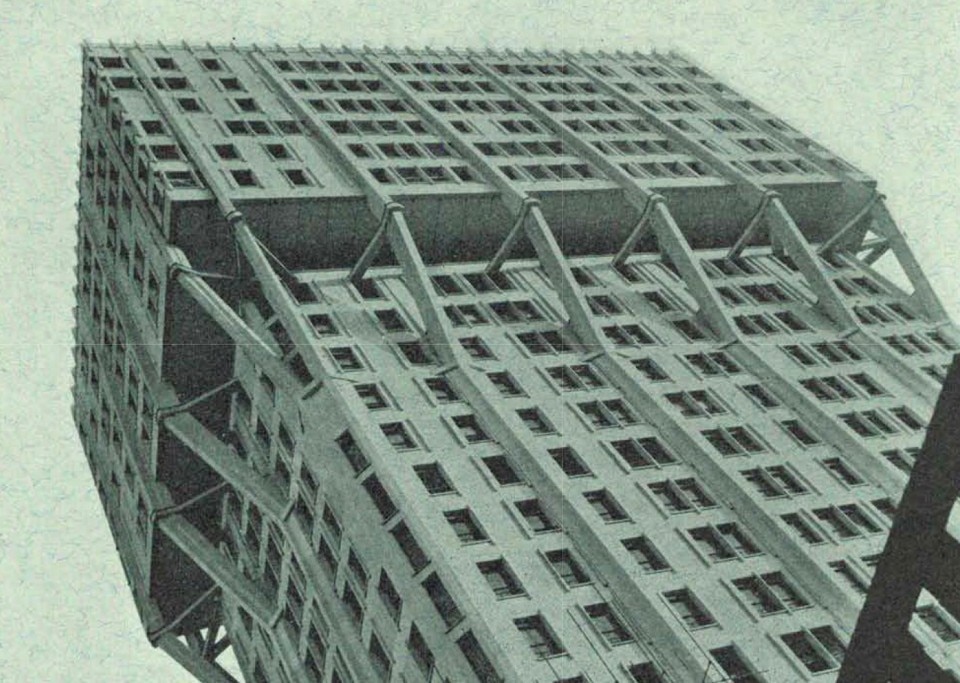

Therefore, the Torre Velasca is a boldly contemporary project for its dimensions (it is 106 meters high), its structure (designed by Arturo Danusso in reinforced concrete) and its functions (offices and flats, besides a few commercial spaces). At the same time, the tower intends to reproduce Milan’s “atmosphere” (another crucial word for rogers), to establish a dialogue with its historic buildings, first and foremost the gothic cathedral and the Filarete tower at the Sforzesco castle.

Evolutions of the project show a progressive shift from a simplified block, clad in a typical International Style curtain wall, towards greater volumes articulation and language complexity. Many of the solutions adopted are clear hints to ancient Milan, and more in particular to the Middle Ages. This is the case, for instance, for the “mushroom-like” silhouette, which also has a functional reason: offices are located in the “stem”, while the “tip” hosts flats, requiring a deeper layout. Milan’s past is referenced also by the half-pilasters showing on each elevation, and turning into aerial buttresses, as well as by the (seemingly) uneven openings’ layout and by the marble and clinker precast cladding panels.

Few projects have triggered so much debate as the Torre Velasca. Presented by the Italian delegation to the XI CIAM – International Congress of Modern Architecture in Otterlo, in 1959, it profoundly upsets British critic Reyner Banham. The Italian Retreat from Modern Architecture is the title of his article on Architectural Review, published in April 1959, where he stigmatizes BBPR’s building, as well as its theoretical premises, as brought forward by Rogers. Misunderstood and opposed by the disciplinary culture (at least in the first moment), the Torre Velasca struggles to get approval also from the general public. In spite of its stated will of “ambientamento” (which could translate to a smooth insertion into its environment), for many years it is commonly regarded as a havoc, and it constantly features within the top-lists of “the ugliest architectures in the world”.

Beyond all dispute, the historic relevance of the Torre Velasca is undeniable for at least two reasons. On the one side, the tower and Gio Ponti’s Pirelli skyscraper (1956-1960) embody more than any other building the two souls of Milan’s post-war economic and cultural “renaissance”, on the threshold between local tradition and cosmopolitan momentum. On the other side, it is precisely starting from the Velasca, and based on Roger’s writings, that Italian architecture enters its post-modern season, whose most interesting expressions are certainly the Neoliberty current and the Tendenza movement.