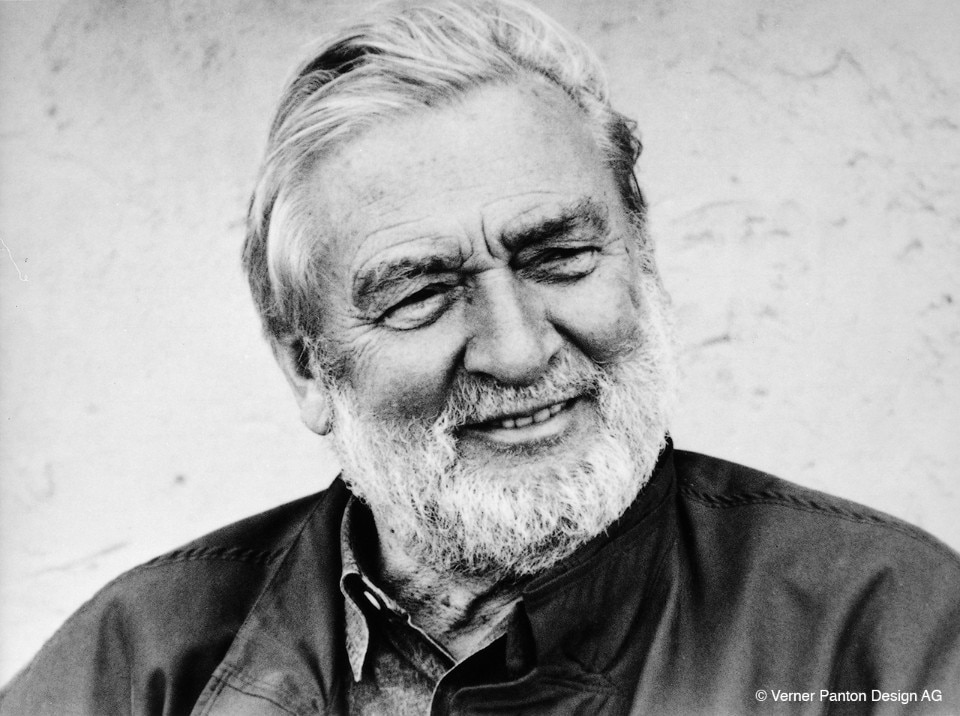

The fame of Verner Panton (Copenhagen, 1926 - Basel, 1998) is due in the first place to the chair that is named after him: the “Panton Chair”, developed starting from 1960 as “Stacking Chair” and later as “S-Chair”, put into production by Vitra in 1967 and included still today in the Swiss brand’s catalogue. The very first single-piece molded plastic chair is commonly considered as the Danish author’s most relevant legacy to the history of product design. A universal icon from the 20th century, it embodies a lot of his creator’s main research themes.

Panton’s trajectory has to be framed in the scene of mid-century Danish design. He moves from Odense to Copenhagen, where between 1947 and 1951 he studies at the Royal Danish Academy of Arts. At the time, the school is actively promoting the evolution of the Nordic country’s tradition in the field of furniture design from craft to industrial production. He is still a student when he starts working with Arne Jacobsen (1902-1971), a behemoth of that age’s Danish design. He participates in some projects that are destined for success, including the famous “Ant Chair” (1952). While Panton separates from his master to open his own firm already in 1955, his experience with Jacobsen will have clear and long-lasting effects on his following production.

From the most rooted tendencies of Nordic design Panton draws the interest for an organic approach to the conception and shaping of objects; on the other hand, he distances himself from minimalism, for instance for his use of color. His distinctive palettes are resolutely anti-purist, pop and even psychedelic, a feature that has certainly contributed to keep him very popular over time.

In parallel, with joyful and ironic optimism, the young designer also grasps and builds on the technological momentum that is crossing the Western world in the 1950s. A sensible and yet daring research on materials quickly turns into one of his works’ main elements of interest. Panton experiments not just with plastic, but also with metal, glass, synthetic fibers, to make a few examples. He is supported in his path by several manufacturers that he builds a fruitful exchange with over the years, first in Denmark, where he works among the others with Fritz Hansen, Louis Poulsen and J. Lüber, and later in Switzerland, where in 1963, right after moving to Basel, he starts a decades-long collaboration with Vitra.

The “Panton Chair” is just one of countless seats designed by Panton, many of which are deeply innovative in several regards, not least for their “performative” potential. Panton’s chairs rotate as the “Cone Chair” (1958), or they hover in the air as the “Flying Chair” (1963-1964), and when they don’t fly they sometimes inflate. Domus first publishes the inflatable “light-as-air” seat produced by Danish manufacturer Unika Vaev in 1963. In the words of the magazine’s editors, “it is made of blue transparent plastic, it has various air chambers and it functions as a little balloon”. To conclude, they sometimes ironically draw inspiration from a type of cheese, as is the case for the “Emmenthaler” series for Cassina (1979), few one-off pieces shown at that year’s Copenhagen furniture fair. To explain their unheard-of configurations, Panton declares to Domus that “besides being useful, each chair ought to exist in its own right. When the chairs are arranged next to one another they should form a ‘seat landscape’ which refuses to be just functional”.

The “Living Sculpture” sofa (1970-1971) and the “Living Tower” from 1969 are variations on the theme of the seat-cabin, objects but also spaces in their own right, which interpret the climate of those anxious years of cultural revolution, searching for new ways of inhabiting the domestic interior. On the “Living Tower”, Domus comments in curious and enthusiastic terms that “the core of the house has turned into a cave: soft, comfortable, quiet and full of colours”. The fabrics designed by Panton on the threshold of the 1970s, such as the “Mira-X-Set” collection from 1969-1971, and his several lamps are just as experimental.

When analyzed in chronological order, the “Flowerpot Lamp” (1968), the “Globe Lamp” (1969) and the “Ball Lamp” (1969-1970) witness a similar pressing need to overrule the conventional boundaries of the isolated object, and to interact in a truly organic fashion with the space surrounding it and with its users. The high point of this process of expansion of the lamp is the monumental site-specific ceiling that Panton realizes between the 1970s and the 1980s for his own house in Binningen, Switzerland, inspired by the “Shell Lamps” from the previous decade.

Binningen’s living room is a sober but relevant example of “total environment”, that is an interior where the designer takes care of each and every surface and elements at all scales, orchestrating an exuberant, and yet fully controlled, chemistry among its various components. Panton is a staunch supporter of this approach, and it is not by chance if most of the objects mentioned above were originally conceived as part of a total environment. The most extraordinary of them are the Astoria Hotel in Trondheim, Norway (1960), the Varna Restaurant in Aarhus, Denmark (1971), the interiors of Der Spiegel Headquarters in Hamburg (1969) and above all the unforgettable set ups commissioned by Bayer.

Visiona 0 (1968) and Visiona 2 (1970) are the chemical-pharmaceutical industry participations to two editions of the Cologne Furniture Fair. For several years, on that occasion Bayer rents a boat and entrusts a designer or an architect the redesign of its interiors. In particular, Panton is tasked to emphasize the potential of Dralon, a new synthetic fiber, both resistant and versatile. He turns this request in the occasion to take to the extreme the potential of an organic approach to the architectural space. Within the installation’s main room, the box’s right-angled configuration is entirely overridden, his ceiling and walls replaced by the curves of a soft, brightly-colored cave, full of alcoves and reflections.

“Visiona 2” is possibly Panton’s only total environment that survived to the present day, as part of the Vitra Museum’s collections. It is an invaluable statement to a one-of-a-kind, bold and successful combination between a designer’s outstanding abilities, a client’s visionary attitude and the spirit of an age, around 1968, when the possibility to radically rethink the ways of conceiving and inhabiting space seemed within reach.

In the words of Paola Antonelli (from Domus 776, November 1995):

The Sixties were a time of uneasy and immoderate adolescence. The free and apparently organic forms of integral plastic were numberless. From the chair by Verner Panton in Denmark (1960) to the transparent armchairs named after flowers (1960) by Estelle and Erwing Laverne of the United States. In Finland, Japan, France and Italy, the injection mold became the matrix of a new world