Norman Robert Foster, commonly known as Norman Foster, was born in Manchester in 1935 and studied first at his local University (from where he graduated in 1961) and then at Yale University, where he obtained a PhD thanks to the Henry Fellowship scholarship. During these fundamental years in the USA, he had the opportunity to work with Richard Buckminster Fuller, and was influenced by teachers such as Paul Rudolph, Serge Chermayeff and Vincent Scully.

He made his professional debut together with Richard Rogers, who he had met at Yale, and with whom he founded and managed the Team 4 group in London between 1963 and 1967, together with Wendy and George Cheeseman. Team 4 was responsible for the design of the Reliance Control Factory in Swindon (1966-1967), a factory inspired by the lightness that was typical of American steel buildings, and one of the buildings chosen by the critic Peter Buchanan to illustrate the neologism “high-tech” which was coined in 1983. The term described works by young designers on the English scene at the time (including, as well as Team 4, Nicholas Grimshaw), whose characteristics of the exaltation of the construction process - inherited from some of the most important figures in early-twentieth-century rationalism who in turn had been influenced by the experience of nineteenth-century engineering - are seen as the only possible style for contemporary art and architecture. This is an approach that Foster has maintained unchanged throughout his career, despite his progressive move from his first contracts for the construction of industrial warehousing to the winning of prestigious international calls for tender and the building of buildings with a very strong public character.

1967 also saw the founding of Foster Associates (later renamed Foster + Partners), which over the years has grown to employ more than five hundred designers divided among offices with headquarters in London, Berlin, Frankfurt, Paris, Hong Kong, Singapore and Tokyo. The winner of countless international awards, Foster + Partners was conceived according to the model of the great American firms, in which the work in the result of a collective effort, and it currently handles not only architecture but also urban planning, engineering, interior design, exhibit design and graphics.

The first important project following the break from Team 4 saw Foster’s debut in the field of cultural building design, with the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts on the campus of the East Anglia University (1974-1978), which marked not only the beginning of a profitable collaboration with the Sainsbury family (one of the most important of Foster’s patrons), but also led to international recognition for Foster Associates, which then went on to design buildings destined to become high-tech icons from the 1980s. These include the Centre d’Art Contemporain et Mèdiatheque di Nimes (1984-1983), known as the “Carrè d’Arte”, and the famous headquarters of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (1979-1986). Universally recognised as a turning point for Foster, the elegant forty-one-floor high building has a steel frame which supports floors structured like suspension bridges and modelled like cranes held between the angles of the supports. A very technologically-advanced solution - which led to the skyscraper’s record as, for a long period of time, the most expensive building of the modern era - aimed at the creation of internal spaces which are completely uncluttered and fully air-conditioned. On the contrary, in Nimes, the building was a forerunner for a number of themes that Foster examined with the Cranfield University, which he had begun a few years later but which was inaugurated in 1993, together with the Carrè d’Art. Here the proportions seek dialogue with the classicism of the adjacent remains of a Roman temple on the one side and with the traditional model of the houses of the French Midi, with their shady courtyards, on the other. These courts - as is the case with the mediatheque - serve as the core for the entire layout, distributed by spectacular glass stairways with stainless steel supports fixed to squared beams, a solution which was re-proposed in the Cranfield campus.

The Hong Kong Bank experience led to numerous contracts in the Far East, such as the new international airport for the island built on the artificial atoll of Chek Lap Kok (only completed in 1998) and the successive Kansai airport in Japan (1988). In particular, the Hong Kong terminal is the nerve centre of a highly technological complex which includes an underwater tunnel and an extremely long suspension bridge developed on two levels; one for road traffic and the other for railway connections. It is a tribute to structural engineering, with the hall covered by a futuristic seamless diagonal-grid steel and glass roof which was shaped to resemble the wings of an enormous bird.

In England, Foster restructured the historical Burlington House at the Royal Academy of Arts (1991), which was transformed into the new location for the Sackler Galleries, inverting the access routes to the site and displaying the façade of Burlington House - hidden for over a century by earlier expansion works - in a new covered courtyard; he created the brand new and mastodontic terminal for Stansted Airport, designed at the end of the 1970s and opened in 1991, and built from a sequence of PVC membrane parasols supported by structural trees in tubular steel, and he reorganised and re-qualified the access system for the British Museum, constructing the glass roof of the Great Court (1999-2000), the design for which can be read as an evolution of the concepts applied to the Sackler Galleries.

Among his other works, Foster also built the headquarters for his studio, set on the banks of the river Thames in the Battersea area of London (1991), perhaps one of the most successful tributes by the architect to the modernist principles of Bauhaus, which inspired the technical solutions developed to create the luminous interior and the image of structural simplicity, this time achieved through a reinforced concrete frame which also set out the rules for the choice of materials and for the interiors. In this case, interior and exterior coincided both in terms of form and choice of finishes for the more than nine thousand cubic metres of open space destined for offices, set out over eight floors and furnished with numerous “Nomos” tables (one of the most famous of Foster's designs). In more recent years, the studio has designed the new headquarters of the Middlesex Guildhall Supreme Court (2009-2016), and the recently-completed residential tower at 100 East 53rd Street in New York.

Norman Foster was knighted in 1990 and won the Pritzker Prize in 1999.

In the words of Martin Pawley:

Without compromising his own genius, Norman Foster has avoided the traps of politics, cautious and cowardly aesthetics and the shackles of the old school of British privilege, to nimbly make his way to the forefront

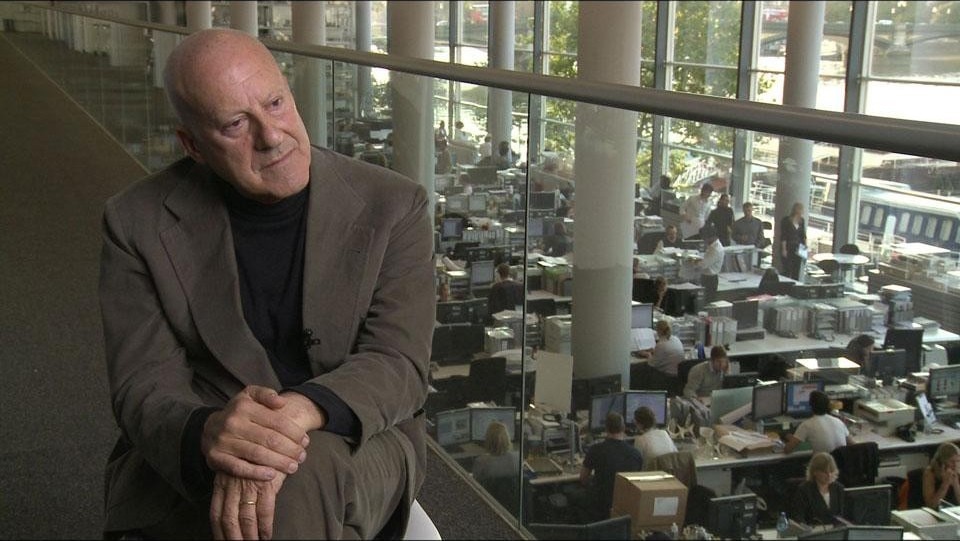

Top image: "How much does your building weigh, Mr. Foster?" film by Norberto López Amado and Carlos Carcas

- Born:

- 1935

- Professional role:

- architect, designer