In 2022, he was back in the news because of a sculpture depicting himself hanged in the bathroom of the Corbellini Wassermann house of the Massimo De Carlo gallery in Milan during Art Week; Not a surprise if the artist is Maurizio Cattelan.

Born in Padua in 1960, Cattelan is among the most popular Italian artists in the world. His works combine humour and the grotesque and question entrenched social norms and hierarchies, the dynamics of cultural production and contemporary politics. A controversial artistic practice, to the point of being defined by some as the “the jokester of the sculpting world”, a nickname with which Cattelan himself, who considers himself an “art worker” rather than an artist, has played and experimented.

Growing up in a humble family, Cattelan soon dropped out of high school to devote himself to work, holding various jobs in post offices, mortuaries and kitchens. He never attended academies or art courses, being completely self-taught. “Making exhibitions was my school”, he said.

His career began in Forlì, Italy, in the 1980s, but soon moved to Milan. In the capital of Lombardy, Cattelan created so-called “non-functional objects”, conceptual sculptures made by welding and assembling recycled elements.

It took me ten years to correct the wrong education I received from my family: work seen as a tool to survive. Instead, I wanted a job that served to emancipate me.

The self-portrait Lessico Familiare, created in 1989, is considered his first work of art, depicting the artist forming a heart on his bare chest with his hands. But his official debut coincides with the presentation of the work Stadium 1991 at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Bologna: 11 players of the Cesena team and as many Senegalese immigrants, employed as labourers in the Veneto region, compete in a game of table football at the extremities of a very long foosball table.

He moved to New York in 1993.

From the very beginning, Cattelan has made fun of the same art world by which he has often been targeted, even incorporating criticism of him into his work to emphasise it. Jonathan P. Binstock, curator of contemporary art at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, called him “one of the great post-Duchampian artists and also a smartass”.

For Errotin, le vrai Lapin (1995), a work exhibited on the occasion of the opening of the gallery of Emmanuel Lapin, a gallery owner and notorious womanizer, Cattelan persuaded him to wear a giant pink rabbit costume shaped like a phallus, playing with words: “lapin” in French means precisely rabbit.

For Another Fucking Readymade (1996), made for an exhibition at the de Appel Arts Centre in Amsterdam, he stole the entire contents of another artist’s exhibition to pretend it was his own. The police had to insist that he return the loot, threatening him with arrest.

Grotesque comedy and disguises have always characterised his practice. In 1998, a volunteer paraded through SITE in Santa Fe wearing an enormous caricature costume of Georgia O’Keefe made of papier-mâché; in the same year, a person dressed as Pablo Picasso welcomed visitors to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

What I do is perhaps difficult to understand. It does not come with a single message or a single interpretation. Certainly, not giving a precise definition to the work means allowing it to live longer.

In his early work, Cattelan often made use of taxidermy, which, quoting Nancy Spector, Deputy Director of the Guggenheim, “presents a state of apparent life that is based on real death”. In particular, he has created installations in which taxidermied animals are taken out of their natural context and re-inserted into paradoxical narratives. These include Bidibidobidiboo (1996), depicting a squirrel lying in the kitchen with a gun at its feet after committing suicide. According to an anecdote, Cattelan's sister Giada was going through a difficult time and told her brother about it, who asked her if she had ever thought about suicide. Upon contemplating the work, Giada felt a strong connection with it: she later declared that it was crucial for her to move on and get rid of her dark thoughts.

Personalities from the art world, dead animals, family members. Cattelan’s macabre humour did not save even ecclesiastical institutions. If a Tree Falls in the Forest and There is No One Around It, Does It Make a Sound (1998) is a farce of Palm Sunday, a Christian biblical feast, in which the figure of Christ is replaced by a television set: a critique of mass media veneration in contemporary society. And again, in La Nona Ora (1999), a wax replica of Pope John Paul II is struck by a meteor and hung on a red carpet.

From the late 1990s onwards, Cattelan started creating hyperrealistic and caricatural figurative sculptures depicting himself and well-known historical figures: in Him (2001), Adolph Hitler is kneeling on the floor in prayer.

I wanted to destroy it myself. I changed my mind a thousand times, every day. Hitler is pure fear, he is an image of terrible pain. It hurts even to pronounce his name. Yet that name has conquered my memory, it lives in my head, even if it remains taboo.

In line with his entire career, his participation in the Venice Biennale has always provoked controversy and conflicting opinions. For the 1993 edition, Cattelan made Working Is a Bad Job, renting the space allocated to him to an advertising agency that installed a billboard to promote a new perfume. A few years later, during the 2001 Biennale, he installed a life-size HOLLYWOOD sign on the largest garbage dump in Palermo, Sicily.

For me, art is empty, transparent: it is a device to set in motion interpretations that belong to the viewers. In the end they do the artists’ work.

In 2004, Cattelan created an installation for the Fondazione Trussardi in Milan: three puppet children hanged from a tree in the middle of the city centre, in Piazza XXIV Maggio. The disturbing realism of the grotesque representation generated outrage and controversy.

Also in Milan, among his most recent works, L.O.V.E. (2010) is a 15-foot high Carrara marble sculpture representing a hand with all fingers removed except the middle finger, facing the Italian Stock Exchange. Equally provocative was his 2016 intervention in the bathrooms of the Guggenheim in New York, where Cattelan installed a solid 18-carat gold replica of a functioning toilet, inviting paying visitors to the museum to use it. The work, entitled America, intentionally recalls the Fountain made in 1917 by his idol, Marcel Duchamp.

Impossible then not to mention Comedian (2019), a banana taped to the wall exhibited at Art Basel Miami, which caused worldwide talk for days. In a perpetual paradox between art and non-art, the same fruit was eaten during the fair by Georgian artist David Datuna, in an artistic performance entitled Hungry Artist.

Cattelan’s career has spanned many forms and professions, including that of curator. In 1999, he curated the Caribbean Biennale with Jens Hoffmann, a mockery of the very concept of the Biennale. Several artists, including Olafur Eliasson, Chris Ofili and Gabriel Orozco, were invited to a hotel in the Bahamas to participate in an event with no artworks: basically a holiday.

In 2002, he co-founded The Wrong Gallery, described by The Guardian as “The World’s Greatest Small Gallery”: a glass door leading to a 2.5 square foot exhibition space in New York City. After the sale of the building that housed the gallery, the door and the gallery were exhibited in the Tate Modern's collection until 2009.

In 2010, he co-founded the limited edition magazine TOILETPAPER with photographer Pierpaolo Ferrari, a publication that revolves around brightly coloured and surreal images, optical illusions and puns, with no articles or advertisements.

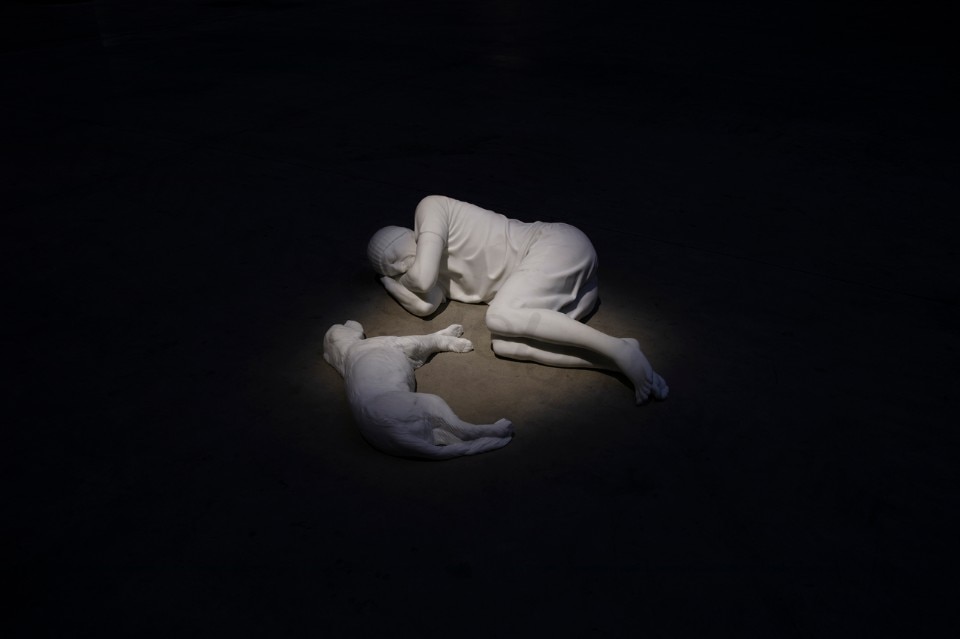

- Cover image:

- Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1999, photo Zeno Zotti, Courtesy: Maurizio Cattelan Archive