The 60th International Exhibition in Venice, curated by Adriano Pedrosa and entitled “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere,” has officially opened its doors, first to the press and insiders, and then to the public from April 20th.

Don’t miss these 10 pavilions at the 2024 Biennale

Between the Giardini, the Arsenale and the historic center, it is easy to get lost in Venice, in this year’s vast Art Biennale. To prevent that and to avoid wasting time, here’s our guide with a map of the must-see pavilions.

View Article details

- Giorgia Aprosio e Carla Tozzi con Alessandro Scarano

- 19 April 2024

For the first time, the exhibition is divided into two parts: a “contemporary core” with works by contemporary artists, and a “historical core” with works from the 20th century from different regions of the world.

The chosen theme, “Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere,” delves into the complex processes that underpin the categorization of individuals as “foreign,” as outsiders, and engages in the recovery of diversity, with a focus on what has historically been marginalized as “foreign cultures.”

Hence, special emphasis is placed on the decolonial theme, evident from the very entrance of the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, where the facade is entirely painted by the indigenous collective Mahku – an intervention poised to resonate as the edition's manifesto under Pedrosa's stewardship.

The inclusion of multiple collectives, embodying a communal and often decentralized approach to art, is another common thread binding the presented artists. Rather than prioritizing national distinctions, the curator appears to have orchestrated a cohesive, expansive thematic initiative that begins with artist selection and extends into a rich program of performative interventions. This represents a notable departure, yielding a result reminiscent of the recent Documenta 15, diverging from the traditional Biennial format.

To be a stranger everywhere is to be at home nowhere and yet perhaps everywhere: reflections on the structures of life permeate this Biennale, running through various exhibits.

A standout feature of this edition is the painting gallery housed within the Corderie dell'Arsenale, showcasing works by luminaries such as Aligi Sassu, Domenico Gnoli, Mario Tozzi, and Simone Forti, among others. These works are displayed on the iconic glass easels designed by Lina Bo Bardi, organized within the exhibition in a manner mirroring their usual presentation in the “home” of Pedrosa, the artistic director of the permanent collection at MASP in São Paulo.

To be a stranger everywhere is to be at home nowhere and yet perhaps everywhere: Reflections on the structures of life permeate this Biennale, running through various exhibits. Beginning with Nil Yalter's iconic mobile home “Topak Ev,” positioned at the entrance to the central exhibition, the exploration extends to the Corderie, with Antonio Jose Guzman and Iva Jonkovic's indigo fabric structure and artist Daniel Otero Torres' expansive architectural installation “Aguacero,” which addresses the theme of water supply in Latin America. There is also the “other” pavilion, designed for the Giardini by artist Sol Calero.

With the participation of some 90 countries, 30 side events, and 332 artists, the Biennial emerges as an expansive and comprehensive exhibition capable of leaving even the most seasoned visitor with aching feet. Coupled with the myriad side events, performances, and exhibitions organized by museums and galleries, the lagoon is transformed into an open-air haven for contemplation. Comfortable shoes, a spirit of exploration, and a curated list of 10 must-see pavilions are indispensable for those embarking on this journey between today and November 24, 2024.

1. Luxembourg, A comparative Dialogue Act

Metal tiles engraved with exhibition notes rest atop large speakers, gently vibrating the surface as sound waves permeate the space. The Luxembourg Pavilion is an infrastructure for sound transmission. Its four walls, more aptly called “sound walls,” stand as the central element of the intervention created by artist Andrea Mancini and the Every Island collective. These distinctive walls will double as instruments during performances, activating the space throughout the Biennale. In the absence of artists, they will play a curated library of recorded sounds and songs produced during residencies. The project encompasses a series of artist residencies, cyclically transforming the space into a hub of artistic creation through a groundbreaking collaboration between four emerging artists from diverse backgrounds: Spanish musician and performer Bella Báguena, French transdisciplinary artist Célin Jiang, Turkish artist Selin Davasse, and Swedish artist Stina Fors.

2. Japan, Compose

A network of intertwining pipes and cables traverses the pavilion, originally designed by architect Takamasa Yoshizaka in 1956. Drawing inspiration from the mechanisms used in Tokyo subway stations to thwart water leaks, Yuko Mohri presents two works for this year’s Biennale that revolve around the theme of cooperation. Mohri explores the notion that facing emergencies and crises in today’s world can serve as a catalyst for innovation and creativity. The pavilion is engulfed in a sensory symphony, with scents, lights, and sounds emanating from electrodes embedded in select fruits, harnessing moisture to generate electrical impulses. The intensity of the lights and sounds gradually diminishes as the fruit succumbs to decay. Throughout the space, the rhythmic drip of the pipe system creates a sense of perpetual motion, animating an environment that seems to possess a vitality of its own.

3. France

Photo Jacopo la Forgia

Photo Jacopo la Forgia

Photo Jacopo la Forgia

Photo Jacopo la Forgia

Photo Jacopo la Forgia

Photo Jacopo la Forgia

An aquatic realm beckons, inviting visitors to glide through a dance-like immersion in the poetic imagery of Julien Creuzet (Paris, 1986). The French Pavilion undergoes a remarkable transformation into a vibrant hub where stories, symbolism, and traditions intersect, drawing from a fluid geography that stretches from Martinique – where the artist lived for many years before returning to Paris to study art – to Africa, and resonates amidst the waves of the Venetian lagoon. The installation consists of over eighty sculptures, and intricate colored nets suspended in the pavilion’s halls, while phytomorphic marine entities seem to float in the air. Meanwhile, divine creatures move across large screens, inviting visitors to travel to this faraway place and reconnect with their senses.

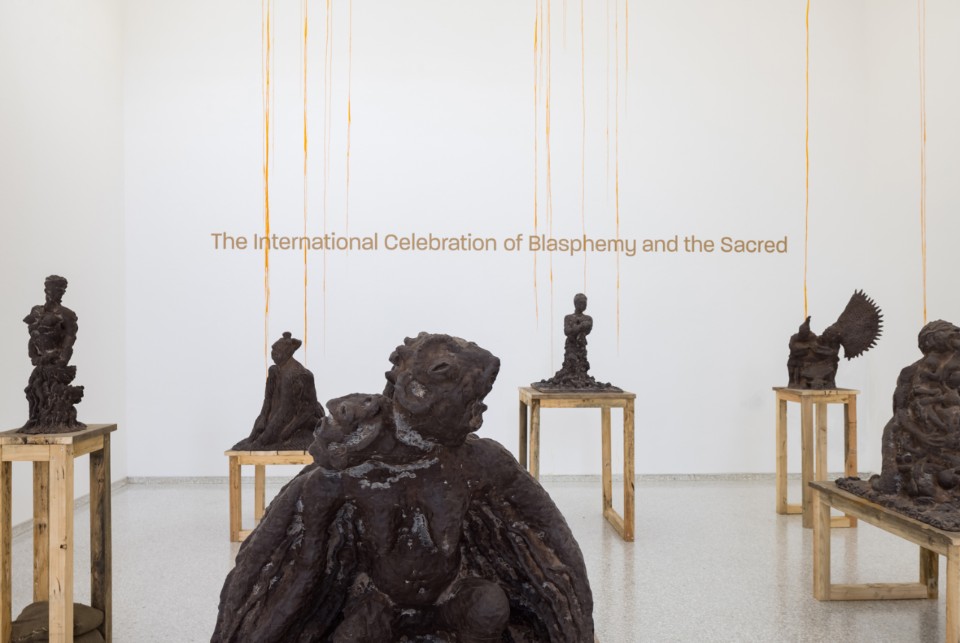

4. The Netherlands, The international celebration of blasphemy and the sacred

The Dutch Pavilion project is not just an intention and inspiration; it is a tangible manifestation of decolonization. At its core is the CATPC collective, a coalition of Congolese artists who work on plantations. Through the creation and sale of artwork, they have reclaimed their ancestral lands and transformed them into thriving agroforestry systems. The sculptures on display are made with clay from the ancient forests near Lusanga in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, then reworked with palm oil and cocoa in Amsterdam. CATPC’s critique underscores the need for art institutions to critically examine the origins of their funding. They spotlight the paradox that multinational corporations, which exploit plantation workers, also contribute to projects supporting art and culture.

5. Australia, kith and kin

kith and kin serves as a memorial to every living being throughout history, beginning with artist Archie Moore’s personal lineage. This extensive hand-drawn genealogical chart meticulously traces Moore’s First Nations connections across more than 2,400 generations spanning 65,000 years. This delicate intervention, reaching up to the pavilion’s ceiling, resembles a celestial map depicting the ancestors of the Kamilaroi and Bigambul tribes, rendered in chalk on blackboard walls. Yet, beneath its celestial beauty lies a somber narrative – the chart starkly illustrates the decline of Australian Indigenous languages and dialects, lost to the ravages of colonization. Moments of erasure, evident in the gaps between names, reflect the atrocities inflicted on Indigenous communities. The title “kith” and “kin,” chosen for the exhibition, is now a generic reference to “friends and relatives,” having gradually lost its ancient meaning. This mirrors the fate of Moore’s ancestral names, which have slowly severed their connection to the concepts of “countryman” and “homeland.”

6. Czech Republic, The Heart of a Giraffe in Captivity Weighs Twelve Kilograms Less

The Czech Pavilion presents for the first time in Italy the project "The Heart of a Giraffe in Captivity is Twelve Kilos Lighter" by artist Eva Koťátková. The artistic intervention tells the story of Lenka, who was captured in Kenya in 1954 and brought to the Prague Zoo, where she became the first Czechoslovak giraffe. Lenka survived only two years in captivity and remained an object of curiosity even after her death. Her taxidermied body was donated to the National Museum in Prague, where it was displayed as a simple museum artifact until 2000. The entire project is born from a collaborative perspective, with the artist working with Himali Singh Soin, David Soin Tappeser (Hylozoic / Desires), Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, and groups of children and elders. Inside the pavilion, viewers are encouraged to enter and occupy fabric tunnels that symbolize large segments of Lenka's body. Here, a tapestry of recorded voices unfolds, telling the myriad potential trajectories of Lenka's story. These voices reimagine plausible scenarios that address the issue of interspecies violence from the perspectives of children, educators, and elders.

7. Italy, DUE QUI / TO HEAR

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Photo Andrea Avezzù

Listening as an encounter and thus as a possibility for self-improvement within one’s own community: Massimo Bartolini’s installation for the Italian Pavilion speaks to the sensibilities of all, inviting viewers to pause and contemplate, recognizing reflection as essential for grasping the present moment. The pavilion’s raw architecture directly engages with the refined design curated by Luca Cerizza, structured around a tripartite space. Upon entry, visitors are greeted by the mystical presence of the Pensative Bodhisattva, evoking a suspended sense of time heightened by the ethereal sound of an invisible organ pipe that harmonizes with the main space of Tesa 1. Within this space, a composition by Caterina Barbieri and Kali Malone reverberates amidst a sprawling array of innocent pipes that can be traversed in different directions. In the center, a circular sculpture pulsates with constant energy, serving as a space for encounter and meditation. Upon exiting, visitors are welcomed into the Virgin Garden, where Gavin Bryars’ composition encourages new connections between humanity and the environment.

8. Taiwan, Everyday War

A dark room and a huge screen greet visitors as they climb the stairs to the prison building. Images of Taipei unfold before them, captured from above by five aerial cameras, revealing a completely deserted city: streets, bridges, buildings – all devoid of human presence. This isn’t CGI, nor is it staged; it’s the annual Wanan Air Drill, offering a glimpse into a forecasted war, as depicted in Yuan Goang-Ming’s single-channel video work Everyday Maneuver. The Taiwanese artist’s blend of video and installation art explores the paradoxical and harsh intrusion of war into the fabric of everyday life. Not to be missed is Prophecy, an Ikea-set table with empty dishes, where cutlery and crockery quiver to the syncopated rhythm of explosions.

9. Serbia, Exposition Coloniale

In addition to the official history of memory, there exists an unofficial history of remembrance. This is the premise of the exhibition “Exposition Coloniale,” which Serbia is presenting at the 2024 Venice Biennale. While the façade of the pavilion bears the monumental inscription “Jugoslavia,” recalling a nation geopolitically dissolved by the devastating conflicts of the 1990s, the interior spaces are transformed into scenes of memory by multidisciplinary artist Aleksandar Denić, who long ago moved from Serbia to Germany. Denić’s immersive intervention evokes impressions that are not tied to a specific place or time, but rather familiar motifs that are easily recognizable by all, inducing a sense of déjà vu in the viewer. Steam billows from the door of a sauna, a telephone rings at regular intervals alongside flashes from a photo booth. In the kitchen, souvenirs inhabit a lifeless aquarium. Manipulated, altered, and constructed like a movie set, the pavilion’s environments evoke a vanished personal and national identity.

10. Nigeria, Nigeria Imaginary

Nigeria has chosen a 16th-century palace in the heart of Dorsoduro, Palazzo Canal, as the venue for its pavilion at this year's Biennale. The project was inspired by the history of the Mbari Club, a cultural centre founded in 1961 in Ibadan by Ulli Beier, a reference point for African artists, including Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe. Just like the Mbari Club, the project curated by Aindrea Emelife proposes itself as a place of confrontation and laboratory of ideas, through the works of eight artists who, experimenting with different media - painting, sculpture, multimedia installations, augmented reality - trace a discourse that, starting from the elaboration of the past, lays the foundations for the Nigeria of the future.

Opening image: The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred, CATPC, Renzo Martens, Hicham Khalidi, 2024. Photo Peter Tijhuis