Living art parks. Temporary interventions to symbolically kickstart redevelopment. Tactical urban planning operations. Unlawful changes of use. Participation from below. With the pandemic, cities have changed: physically, economically and socially. Those who administrate them have realised that the old model no longer works. That there is a need for regeneration. And that there are also tools that can accelerate the transformation: art is the first one.

Patrick Tuttofuoco designed the most recent example of emotional repurposing of a public space. X is the installation designed for the Vetra Building, a real estate operation which now occupies the buildings of the former Tax Collector’s Office in Piazza Vetra, in Milan, but which also aims to give the inhabitants a new square, a gateway between neighbourhoods, an invitation to interact with each other. “Over the last two years, the relationship between people and the city has changed in size,” says Tuttofuoco. “Covid transformed our relationship with public spaces and made them essential. We all wanted to be outside. Piazza Leonardo da Vinci, in front of the Polytechnic University, was full of people more than ever: it was beautiful to see, and it reminded me of the importance of sharing, of how ideas are created”. Local paths have become places of intercultural, intergenerational and synergetic decompression. “Public art has always sensed this need: the requests that the artists bring into play often serve to raise precisely this type of awareness”.

Tuttofuoco thinks back to the late 1990s and his first performances “designed to physically engage the public”. He had set up a human-scale hamster wheel in Corso Vittorio Emanuele, the city’s main street. When he got on and started running, some insulted him, some cheered him on, others got on the wheel after him. Not everyone realised that they were – not metaphorically – on the same wheel, busy maintaining a balance in a society that asks you to never stop. “Although devoid of any immediately intelligible meaning, “Criceto” aroused attention and amusement, certainly, but it was also incorporated into the experiential memory of those people”.

The effect he is talking about is that kind of magnetism that occurs when a work of art literally pulls you into it, immediately generating a constantly changing collective energy. Thinking about it, Patrick Tuttofuoco quickly recalls two episodes.

The perception of metropolitan space must change.

The first was in Kanazawa, Japan, where James Turrell had created one of his “Skyspaces”, rooms with windows overlooking the sky: “It doesn’t matter if you are used to meditating: when you get thrugh that door, you start contemplating a glimpse of infinity”.

The second was in London, in the Turbin Hall of the Tate Modern, where Olafur Eliasson had brought “The Weather Project” installation, a gigantic artificial sun, under which people would lie down to capture its strength and heat. “Eliasson was able to do this with an important, muscular production, but without killing the poetry”.

In fact, it is not necessarily the case that art knows how to play a leading role while remaining one step behind the ego of the artist. Especially when it is public: “The artist is always called upon to deal with complexity: they must intercept a place and enhance its lines by deploying a very simple form that can enter the lives of those who pass by, but without being intrusive”. If it works, that space becomes a pole of attraction. He cites the creative operations of strategic urban planning that changed the use of Via Venini, which became Piazza Arcobalena thanks to a whale painted on the ground and ping-pong tables.

“The perception of metropolitan space must change: abroad, even in ugly places, it is felt like a continuation of property. If it is public, it belongs to everyone, and therefore also to me, and it must be looked after carefully. There are drunk people in the parks, but also families: in the end, the complexity of existence is self-regulating”.

Even Piazza Vetra, in a semi-central position on the map of Milan, has not always been an easy place- the robbery organised by Renato Vallanzasca that ended with a dead person, drug dealing, Cardinal Martini’s invective… “I know what it was like. But I think that, if you want to, you can reverse the energy of a place: the main intervention is real estate, it’s true, but it gives something to the area, an opening between two neighbourhoods, a possibility. We’ll find out what the long-term effects will be”.

In 2018, Tuttofuoco entered the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II with “Heterochromic”, a site-specific project above Carlo Cracco’s restaurant. Then, there was “ZERO (Weak Fist)”, a mobile and itinerant sculpture, designed to relocate to Rimini, Berlin and Bologna. And then there was “Endless sunset”, a 137-metres-long and 30-metres-high installation in Peccioli that enveloped a pedestrian walkway.

Hence the question: how much does the public destination of a work influence its conception? “A lot, but I try not to ask myself that. I am just very careful not to give in to self-assertion: an artist has boundless privileges and infinite responsibilities. So, I always try to get to the heart of the issues that I feel are my own, but then I move on to the issues of the place”.

The artist is always called upon to deal with complexity: they must intercept a place and enhance its lines by deploying a very simple form that can enter the lives of those who pass by, but without being intrusive.

One of Patrick Tuttofuoco’s latest/next projects is the one he designed for Tirana, where he and Andrea Anastasio were invited by the Italian Embassy and the curator Davide Quadrio: together, they set up “Veggenti”, an exhibition inside a villa in Blloku, now a shopping and nightlife district, working “on the identity of a country with less than three million inhabitants, which in 30 years has seen more than a million people leave. Those who have returned find themselves in a middle ground, which they do not recognise: the change is happening now and it is very fast”.

And by the way: if art is a great tool for regaining possession of the public space, what role will the peripheries of the world and of the metropolis play? The outermost circles are missing: in order for them to be part of the 15-minute city model, that push must come from the municipality. It must invest in energy, and put artists in a position to give something back to the area”.

Targeted interventions, small festivals. “That would be a start. During the Fuorisalone 2021, design arrived in the former military hospital in Baggio. And people discovered that there is a neighbourhood called Forze Armate”. It could do the same with Lampugnano, or Porto di Mare. It happened in 2005 in Ventura-Lambrate, where Patrick Tuttofuoco placed the installations “Luna” and “Park”, the signs of the Varesine merry-go-rounds. It was a sign, the will to keep alive a dream of the children. Anyone passing by today still takes a photo. It is now part of the landscape. Art has fulfilled its task.

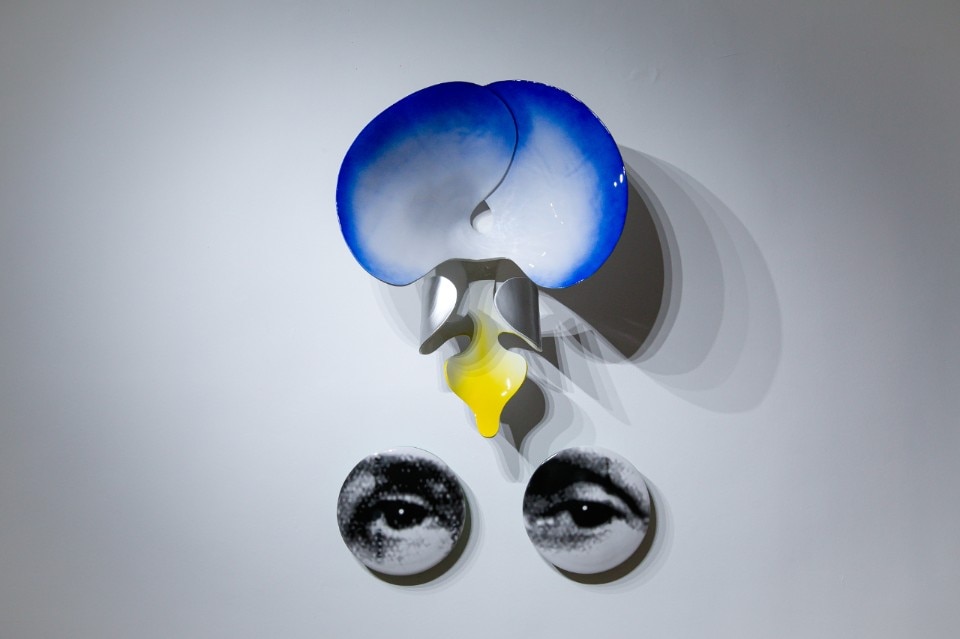

Opening image: Patrick Tuttofuoco, “Endless Sunset”, 2020-2021. Photo Luca Passerotti