“Magic is not just sorcery: any kind of enchantment is magic; the basis of art is nothing but enchantment. Perhaps art is the only enchantment granted to humans: and it bears all the characteristics and types of enchantment: it is the evocation of dead things, the apparition of distant things, the prophecy of things to come, the subversion of the laws of nature, brought about by the imagination alone”. This is how Massimo Bontempelli, the Italian writer and essayist, in April 1928 described the adjective ‘magic’ - an adjective that Bontempelli himself used during those years to talk about a new cultural and artistic movement called Magic Realism.

Cagnaccio di San Pietro

One of the leading figures of Magic Realism, a nonconformist and rebellious artist during the Fascist era, has been brought back to public attention after years spent in oblivion.

View Article details

- Valentina Petrucci

- 25 November 2021

It was the German critic Franz Roh who first used this oxymoron in 1925 as a way of defining a style that was not really a style, but which summed up a way of perceiving the everyday, the reality, opposing the rules of Futurism or Expressionism and starting from the rules of Renaissance classicism. “I hear some speak, a few with joy, others with resignation, of a return to the classical. Some people mean classicism. But even those who think of the Greeks are wrong, and I don’t want to use the word ‘return’. Classical is not a determination of time, it is a spiritual category. In reality, classic is any work of art that manages to escape from its own time and from any time at all. (...) Let us not, therefore, speak of returns; an equivocal word, indeed clumsy. Our age, having emerged from the avant-garde experiences (which were the brilliant burning of the last relics of romanticism), is moving towards its own classicism. The signs are everywhere. The abandonment of chromaticism in music, the smooth walls in architecture, the abhorrence of the adjective in the art of writing. And above all the spirit that seeks to dig deep: art no longer as entertainment, but as a religion of mystery.”

Bontempelli also explains the concept of classicism that these cultured men tried to express through their writings and paintings. But who were the artists who directed their art towards this new sentiment during those years, apart from the two critics already mentioned? The main exponents and interpreters of Magic Realism were Antonio Donghi, Felice Casorati and Cagnaccio di San Pietro. The first two, who were undoubtedly more famous, received various awards over the years from both critics and the general public. This was not the case for Natalino Bentivoglio Scarpa, known (so to speak) as Cagnaccio di San Pietro. The artist, a student of Ettore Tito, already dictated his own style through the choice of his pseudonym. The name Cagnaccio was his family’s nickname, while “di San Pietro” referred to San Pietro in Volta, his parents’ town in the Venetian lagoon. His pictorial style is precise, he rigorously paints the bodies, interpreting a harsh, inclement reality. A rebellious artist, non-conformist in his choice of subjects for his works, he was appreciated more by his colleagues than by the critics of the time, leading him to a lack of fame.

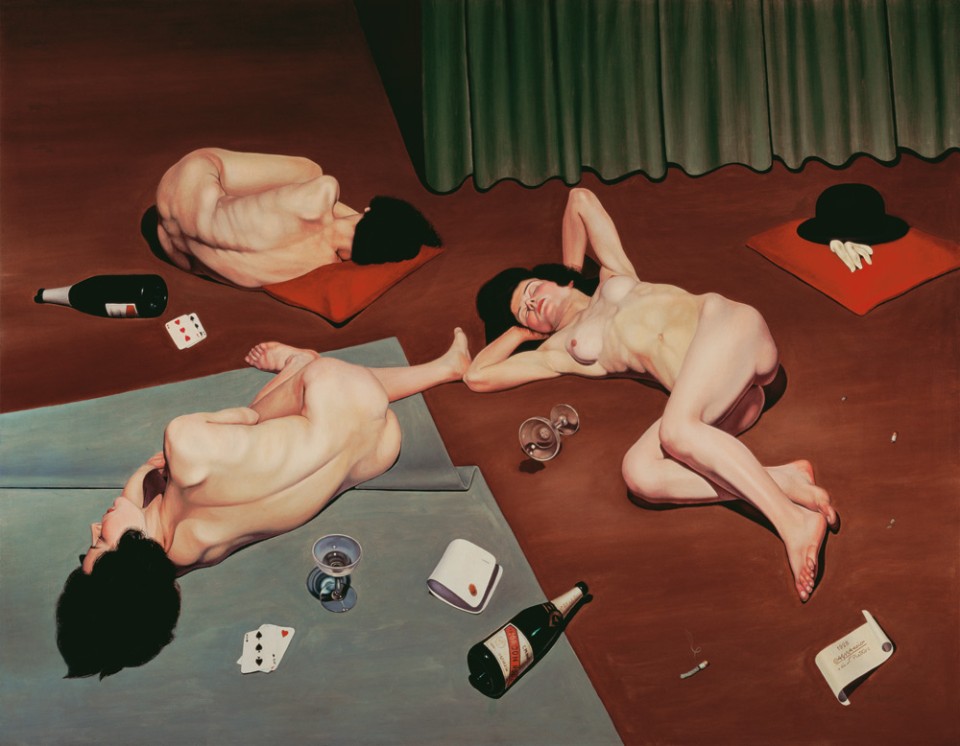

His works were provocative and denounced the Fascist regime that at the time dictated all cultural guidelines. At the 1928 biennale, where Margherita Sarfatti, a well-known patron and art critic as well as the Duce’s lover, was on the commission, Cagnaccio presented one of his best-known works: After the Orgy. The framing is bold, and the viewers feel as if they were standing just inside the room, looking down on three women lying naked on the floor. Overturned glasses, empty bottles and playing cards depicting only two suits, spades and hearts, perfectly reversed in the representation. The scene is geometrically divided into four parts by the green carpet and the curtain of more or less the same colour, while the red floor, a warm colour in contrast to the cold green above, envelops the scene. The bodies are depicted perfectly, both in musculature and pose. The swollen breasts of the three women, contemporary Danae, tell the story, and the genius of the artist lies in the fact that he does not limit himself to mere representation but enters into the perfect reconstruction of the scene. On the ground, in fact, we can also spot a pair of man’s cuffs provocatively bearing the fascist emblem. This stands as a strong aversion to fascism and its corruption. The scandal and indignation weren’t long in coming, and it haunted the artist’s career for several years.

However, over the last few years, this great interpreter of twenty years of elite culture has been brought back to the attention of the general public through monographic and collective exhibitions, such as the one currently showing several paintings by the artist at Palazzo Reale in Milan until 27 February 2022, and thanks to the private market, which often auctions several works by the Venetian master. An extraordinary artwork by Cagnaccio is currently on display in the rooms of Palazzo Crivelli, at the auction house Il Ponte in via Pontaccio 12, in Milan: Nudo in riva al Mare. The work, to be auctioned next 30 November, sums up the style and elegance of this extraordinary artist who died prematurely at the age of 49. He was a painter, an interpreter of an extraordinarily lively cultural period, of sparkling and controversial themes that today remind us of the eager attempt to create culture in a hard but prolific time.

- Cagnaccio di San Pietro Dopo l’orgia, 1928, oil on canvas. Private collection (Photo Mondadori Portfolio / Electa / Luca Carrà)